A woman who murdered a baby she was hoping to adopt previously told a therapist she had anger management issues and drank six bottles of wine a week, a review has found.

The “critical information” disclosed by Laura Castle was not shared with her GP and consequently was not available to the adoption panel that went on to approve her.

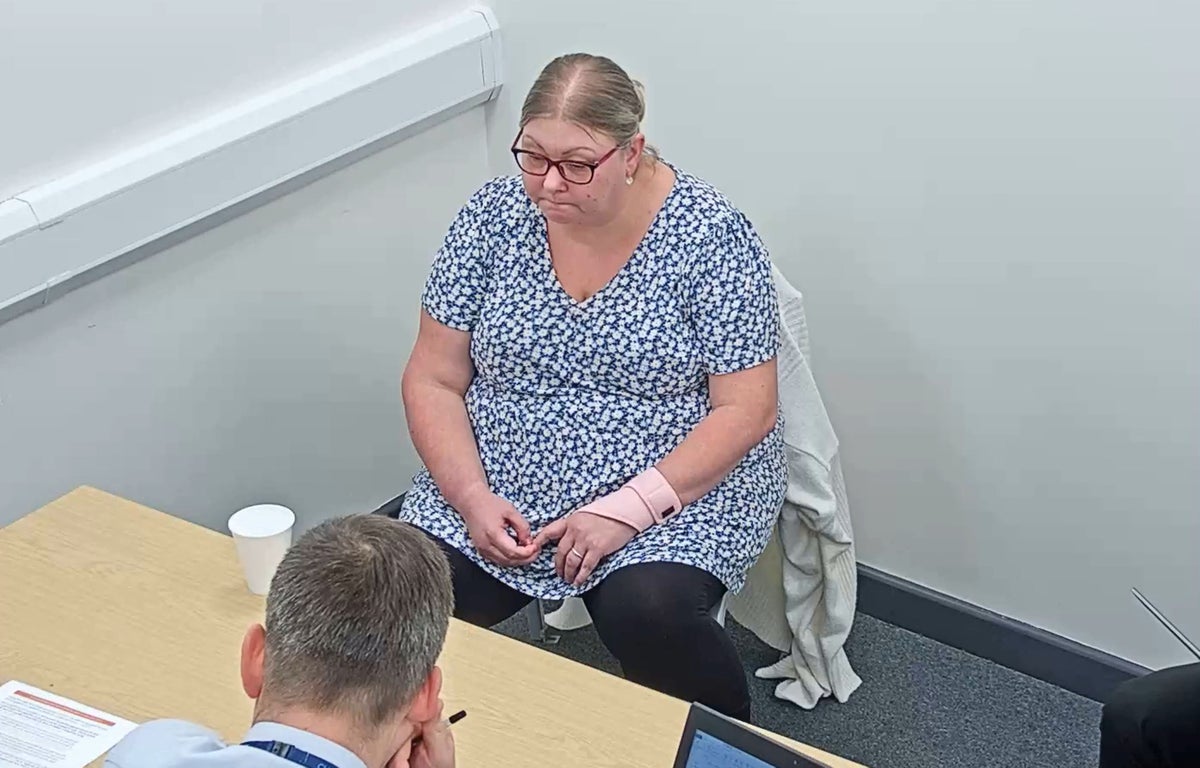

Castle, 38, was jailed in May for a minimum of 18 years for the murder of one-year-old Leiland-James Corkill, who had been placed with her and husband Scott, 35, less than five months before his death from catastrophic head injuries.

The youngster was a “looked-after child” who was taken into care at birth before he was approved to live with his prospective adoptive parents in Barrow-in-Furness from August 2020.

On Thursday, a child safeguarding practice review into the case revealed that Castle, who already had a birth child, was receiving “talking therapy” with an NHS-commissioned service when she applied in January 2019 to be an adoptive parent.

Information held by the First Step programme showed she had issues with “low mood, anxiety and anger management”.

What was not known at the time was that the prospective adopters had not been honest about their debt, their mental and physical health, their alcohol consumption and use of physical chastisement— Nicki Pettitt, review report author

The review added: “This included her self-report that she was often irritable and short-tempered, including shouting too much at her young child.

“She spoke about feeling judged by other parents and that she avoided company. She also reported drinking six bottles of wine a week which impacted on her motivation and mood, although she denied it had an impact on her parenting.”

Castle failed to mention those details in the adoption application process and no safeguarding concerns were raised by First Step, which was not aware the couple had applied to adopt, the review said.

It added the service informed her GP of its involvement with Castle between December 2018 and April 2019 but did not include any details on what was discussed with her.

The review discovered that concerns were raised in September 2020 by a gastroenterologist following a consultation with Castle that she reported drinking 27 units of alcohol per week and it was thought to be affecting her health.

This information was shared with her GP but neither the health issue nor the alcohol use was shared with any other agency.

The Castles did not share the information either and also did not give a full picture about their financial situation.

They had significant loans and credit card debt but the design of their assessment form did not clearly ask for the total money owed, which “enabled the family to disguise what they owed and they were only paying the minimum amount each month”.

Report author Nicki Pettitt concluded “indicators emerged” following Leiland-James’s placement that it “might not progress to be the right placement”, but there were no known signs he was at risk of physical harm.

She added: “What was not known at the time was that the prospective adopters had not been honest about their debt, their mental and physical health, their alcohol consumption and use of physical chastisement during the assessment, at the time of Leiland-James being matched with them or during his time living with the family.

“Learning has been identified that information in these areas should be robustly sought, shared, and considered.

“This is significant, as had the information held by First Step and the gastroenterologist been known, along with the understanding that the prospective adopters were hiding these issues, the assessment could have better reflected the vulnerabilities and potential risks.”

A number of national recommendations have been made, including the need for all health information for adopters and children in the family to be updated and reconsidered at key points in the case.

Revised adoption guidance should include seeking assurance that medical assessments do not rely on the self-report of the prospective adopters.

Following publication of the report, John Readman, Cumbria County Council’s executive director for people, said: “The Castles went through a full eight-month assessment and approval process involving criminal record checks, multiple references and extensive training. No concerns were raised by anyone, in any agency, about their suitability to become adopters.

“What we know now, from the trial and this review, is that Laura Castle deliberately and repeatedly misled and lied to social workers about vitally important aspects of her life, including her mental and physical health, her alcohol use and debts.

“We also know that relevant information about Laura Castle was not shared between agencies and that more could have been done to clarify some of the information we were provided with.”

Professor Sarah O’Brien, chief nursing officer for NHS Lancashire and South Cumbria Integrated Care Board, said: “Information sharing was not good enough throughout the critical stages of the adoptive process. Steps have already been taken locally to address this and a recommendation to change national guidance has also been made.”

Asked if she accepts a safeguarding referral should have been made by the First Step service, she said: “Looking at it now with everything we know, yes I think there was probably enough there or to have at least gone and maybe had a discussion with other professionals who knew the family.”

Lesley Walker, independent scrutineer with Cumbria Safeguarding Children Partnership, said Castle’s self-report to First Step was “critical information”.

She said: “Obviously with reviews the Government guidance is clear, we need to try and avoid hindsight… but clearly it was a really significant piece of information that if shared would certainly have had implications for the assessment of those carers.”

Castle maintained the death was a tragic accident until the day the jury was sworn in for her trial at Preston Crown Court.

She entered a plea of guilty to manslaughter and went on to say that she had shaken Leiland-James because he would not stop crying, and his head hit the armrest of the sofa before he fell off her knee on to the floor.

However, medical experts told the court the degree of force required to cause his injuries would have been “severe” and likely to be a combination of shaking and an impact with a solid surface.

Prosecutors said Castle killed the boy as she lost her temper and suggested she smashed the back of his head against a piece of furniture.

Jurors unanimously found her guilty of murder.