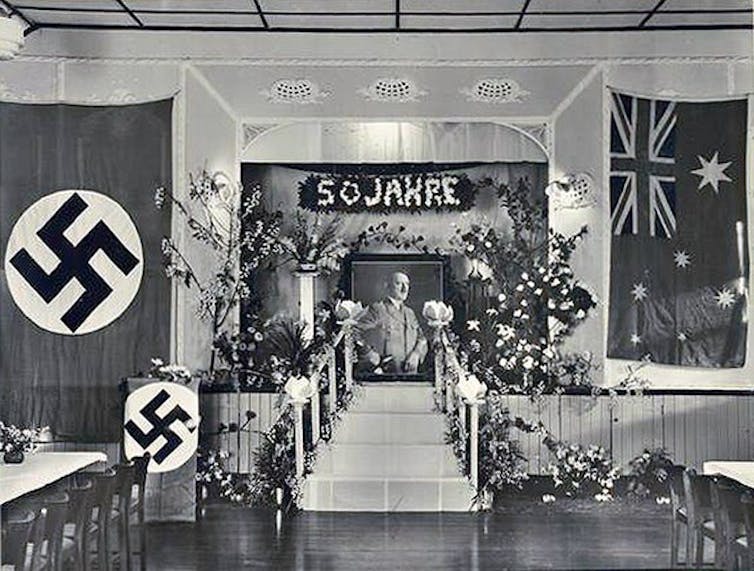

In an age of polarisation, it’s instructive to return to the late 1930s, in the lead up to World War II, when the far left and far right were energised and prominent. In Australia, we tend to think that Nazi sympathisers didn’t exist, or were never significant, but in fact there were documented events in Adelaide and Katoomba that revealed fervent support for Hitler’s rise to power.

Review: A History of Dreams - Jane Rawson (Brio Books)

Contemporaneous left-wing papers suggested, sensationally, that there were 10,000-20,000 Nazis in Australia. There were, at least, 177 paid up members of the Australian Nazi Party and many more sympathisers across the country, with an enthusiastic group in South Australia.

A German Club in Adelaide celebrated Hitler’s 50th birthday in 1939 and support continued throughout the war, with multiple parties held for Hitler’s birthday in 1945, just weeks before the Nazi defeat.

A History of Dreams was inspired to some extent by Nazi enclaves in South Australia, but as Rawson has said “it’s also really about here and now”. It is a surprising, uncategorisable book: part historical novel, part speculative fiction.

In this, it resembles Rawson’s second novel From the Wreck (2017), which was also set in South Australia. The plot of From the Wreck circles around the SS Admella, which sank in 1859 and was famously eulogised by poet Adam Lindsay Gordon. Rawson took a real event and grafted a sci-fi narrative onto it – namely, the story of a shape-shifting alien, who becomes a life-long obsession for one of the shipwreck survivors.

Shrews and suffragettes

A History of Dreams begins on a train in December 1937, when sisters Esther and Margaret and their colourful friend Audrey are in their teens. The young women are bothered by entitled young men bombarding them with questions and rifling through Esther’s possessions, holding up a sanitary pad and a Georgette Heyer novel to ridicule. Esther is called a “feisty little suffragette” and a “shrew”. They are all accused of being “witches” who should be burned.

The young women are far from a coherent group at first. Their class disparities keep them distant. But Esther, Margaret and Audrey unite with their former schoolmate Phyl against such abusive encounters.

Margaret and Esther are from a more prosperous background than Phyl, who lives precariously with her mother, her violent father and her uncle Pip in the bad part of town, near the Valvoline factory. A scene in which Phyl drags a burning mattress outside with her mother – and sells it to a neighbour for his fighting dogs – shows the family’s level of desperation.

After the loss of her bed, Phyl sits by the river and reads Beau Ideal (1927) by Percival Christopher Wren, in which two buddies join the French Foreign Legion. Trapped by circumstance, she dreams of cutting off her hair, strapping her chest, and writing columns about the desert for the English papers.

Read more: In Loveland, Robert Lukins explores a woman's experience of abuse, but at times loses his way

Toppling the bourgeoise with magic

A History of Dreams is concerned with the intersection of gender inequality and authoritarianism. It shows how quotidian incidents – like taunting on a train – may herald dramatic shifts of political power.

Audrey’s father is a left-wing unionist, therefore political struggle is second nature to him. Margaret and Esther’s more comfortable suburban background leaves them ill-prepared when their father becomes progressively hardened towards them. Their dreams of achievement in aviation and the arts become impossible, forcing them into subversive manoeuvres that go against all their conditioning.

Audrey cuts a dashing figure, especially when she wears a coat with nothing underneath and easily “routs a company of rude young men”. Dubbed “Red Audrey” by her enemies – echoing the nickname “The Red Witch” given to communist writer Katharine Susannah Prichard – Audrey does secret experiments with magic, inherited from her great aunt Delia and a long line of witches from Yorkshire.

Audrey has been using her magic to “topple the bourgeoisie”, but she doesn’t introduce magic to her friends until their feelings of fury come to the fore. As the bearer of magic, she is the driver of the witches’ actions, with Phyl as her bolshie sidekick.

The magical dreams they conjure and share with others – often through refreshments – function as a kind of nocturnal storytelling. They encourage sleepers to take action in their waking lives of a sort that is sometimes wildly out of character.

When Margaret is invited to a literary salon by her childhood friend Matt Sands, she and Phyl plan to spike their wine with dreams. They are distinctly underwhelmed by “a pale bunch of pimply-faced, slack limbed city boys”, who read their terrible poetry aloud.

“If this was a prototype for some kind of master race, Australia was in trouble,” Margaret thinks.

When Matt reads his poem “The Spear”, Margaret is shocked by his lack of talent and patronising attitude towards Indigenous people. Phyl disrupts the event, questioning their certainty about what it means to be Australian, saying that she prefers to be a citizen of the entire world, arguing that women’s freedom is “the sign of social freedom”.

The men counter that “the chief business of women must be maternity”, which turns out to be one of central tenets of the incoming government.

Read more: Trauma and loss define Mandy Beaumont's unapologetically feminist debut novel

Galvanised by inequality

Galvanised by the rampant inequality underlying the veneer of Anglo civility, the witches vow to remain unmarried while they explore the potential of their magic. In a debate about the ethics of deploying their gifts, Audrey suggests that there are no physical limits to what they can do, but there are definitely moral limits.

Esther resists limits, declaring: “I’m going to spread beauty and terror any way I can and whatever the consequences.”

Audrey warns:

your magic should never be used to make the powerful more powerful, to make the strong stronger or the weak weaker. This is Robin Hood magic: it takes from the rich and gives to the poor.

“Maid Marion magic, more like,” says Phyl.

This “Maid Marion” or “red” magic can only work on individuals or small groups, at least the way Audrey practices it. A good spell is built on observation and imagination – it does not work unless the witches empathise with the “mark”, no matter how despicable they may be. The spectre of corruption is signposted, suggesting that ruthless forces might co-opt their magic to make the powerless more miserable.

Creeping authoritarianism

For most people living under autocratic governments, the full horror of their circumstances tends to creep up on them gradually. As in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) and the accompanying television series, freedom is taken away by physical incarceration, but also through the denial of literacy and the forbidding of mobility and communication between women.

Phyl’s poverty drives her out to work, providing valuable intelligence about what is really going on. Working at the Foy & Gibson department store cosmetics counter, she learns about the predicament of her workmate Ruth’s family. Some of them are stuck in Germany; others had moved to Tanunda before being forced to relocate due to the proximity of “too many bad people”.

Tanunda was actually the home of Australia’s Gestapo chief in the 1930s, making it especially dangerous for people of Jewish origin. In Rawson’s parallel universe, fascist sympathisers need not hide themselves, because the government is on their side.

Despite these scattered allies, one of the most insidious effects of this totalitarian culture is that trust is eroded, straining human bonds and making people more vulnerable to manipulation.

Working as an underground resistance, the friends each make their own contributions, even when torn from each other by the patriarchy. They suspect one of them is behind the compelling dreams that are broadcast to the minds of all South Australians. To counteract the state-sanctioned ones, Esther dedicates herself to making magical capsules that produce a deep nocturnal blackness instead.

This might be read as a metaphor for the effort needed to resist the mental toll of such a regime – nothingness is preferable to lies.

The weaponising of sleep and dreaming is reminiscent of Ambelin Kwaymullina’s The Interrogation of Ashala Wolf (2012), in which a powerful “Sleepwalker” can do anything in her dreams, but an official tries to break her with “the machine”, which seeks to invade her memories and reveal her secrets.

At times, the men who inhabit A History of Dreams seem like caricatures, too impossibly dreadful to be believable. Thankfully, there are a few male figures who offer nuance. The first is Walt – a queer dance teacher who is sent overseas on a suicidal mission. His partner Benjamin is another warm presence, but he gives up hope when Walt is press-ganged into the army. Later, a “fake husband”, organised by a gay resistance that dare not speak its name, turns out to be a decent human who covertly supports the work of the witches.

The extremity of the novel’s scenario allows Rawson to explore received ideas about family, identity and belonging. Only people operating outside of hetero-normative cultural rules seem able to resist the men in charge. Notably, the witches must renounce matrimony to practice their art and almost all organised resistance comes from the queer community.

Esther’s miserable experience of unwanted pregnancy stands starkly against the ideology of perfect motherhood propounded by the perpetrator of her assault and his cronies. Her ability to parent her daughter Amelia is further shaken by imprisonment and torture, but her allies rally around the raise Amelia collectively, allowing her to carry their magic inheritance into the future.

Rawson’s novel reminds us that although fascism is always with us, so is our capacity for solidarity – and powerful dreaming.

Brigid Magner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.