A solo exhibition in the Royal Academy’s vast Main Galleries is a privilege given only to the most major artists. Following on from shows by heavy-hitters Antony Gormley and Anish Kapoor, South African artist William Kentridge is the latest artist to be accorded the honour. But it’s an honour that doesn’t come without a degree of risk.Gormley and Kapoor’s shows were both solid crowd-pullers, but both were widely criticised for being “bombastic” and “overblown”.

While the Johannesburg-based Kentridge is less well-known, he’s similarly aged – in his late-sixties – no less fond of the grand gesture, and unafraid of massive jumps in scale: from exquisitely made artist books to truly epic live events. But though Kentridge is a brilliant illustrator and stage designer I’ve never been entirely convinced by his art as, well, art.

Born in 1955 to lawyer parents, both active in the Anti-Apartheid struggle, Kentridge worked in theatre and television as an actor before turning seriously to art. And that feels significant as the vast majority of work in this show relates to film or performance in one way or another. Drawing has always been Kentridge’s main medium, and the earliest works are some of the strongest. “Koevoet (Dreams of Europe)” (1984-5), a charcoal triptych showing surreal goings on in café, has a gauche but compelling rawness that is soon lost as Kentridge’s signature style sets in. We’re shown vast numbers of large, densely worked charcoal drawings, all in a highly proficient, illustrative “realist” style that clearly isn’t supposed to be taken at face value – though I’ve never been sure how it is supposed to be taken.

While Kentridge’s focus is on Africa, with hyenas making hallucinatory appearances in night clubs and migrant workers queuing in the vastness of the veldt, his artistic sources are entirely European: Goya, German expressionism, even a touch of Hogarth. This makes sense in the many images of patently bad – white – bankers in their boardrooms, but the light in these entirely monochrome images is so oppressively overcast that sun-baked savannah can easily be read as snowbound steppes and lines of tramping Africans as refugees in, say, Poland. The irony of the fact that Kentridge’s Jewish forebears fled Eastern Europe to escape oppression isn’t, as far as I can tell, explored. Almost all of these images are working drawings for animated films, six of which are shown simultaneously in the enormous Gallery 3. Kentridge makes his drawings move by rubbing out areas, redrawing them and filming the ongoing process. It’s as though the continually pulsing charcoal images are being drawn on the screen as we watch in films such as Tide Table (2003) and Other Faces (2011). Signature Kentridge tropes are established early on, such as having the image break down into abstract elements that reform as, say, maps or bureaucratic forms – and Kentridge loves this sort of printed ephemera, which appears by the shedload, in various forms, throughout the exhibition.

If it’s impossible not to be impressed by Kentridge’s sheer industry, the narratives are hard to follow and it’s difficult to know what’s being said about South Africa today; though in Other Faces a figure looking very like Kentridge gets in a screaming row with a shopkeeper in which race inevitably intrudes. If such harsh realities must be hard for Kentridge – a former anti-Apartheid activist – to face, the painful, paranoid actualities of contemporary South Africa are kept mostly at a rarefied or historical remove in the rest of the show.

Ubu Tells the Truth (1997), an animated retelling of Albert Jarry’s absurdist drama Ubu Roi, starts as a whimsical cartoon, but becomes a punchy and brutally humorous response to the horrific revelations of the post-Apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

But by the time he gets to Black Box (2005), an automated miniature theatre with film and real-life animated objects, Kentridge has become absorbed in the intricacies of multi-media collage almost to the exclusion of his subject matter. We spend a lot of time watching a slow-dancing Anglepoise lamp, but the ostensible theme of the work, the genocide of the Herero people of South-West Africa, is barely discernible. A roomful of tapestries, with Kentridge’s densely patterned ink drawings blown-up to wall-filling scale, impresses amid the prevailing monochrome flatness because these are at least sensual, tactile objects – and they even include touches of colour! A tapestry of shadowy figures packed into an open boat is clearly derived from an old photograph or painting. Yet it’s impossible not to interpret it is a scene of contemporary migrants, making this one of the most powerful images in the show.

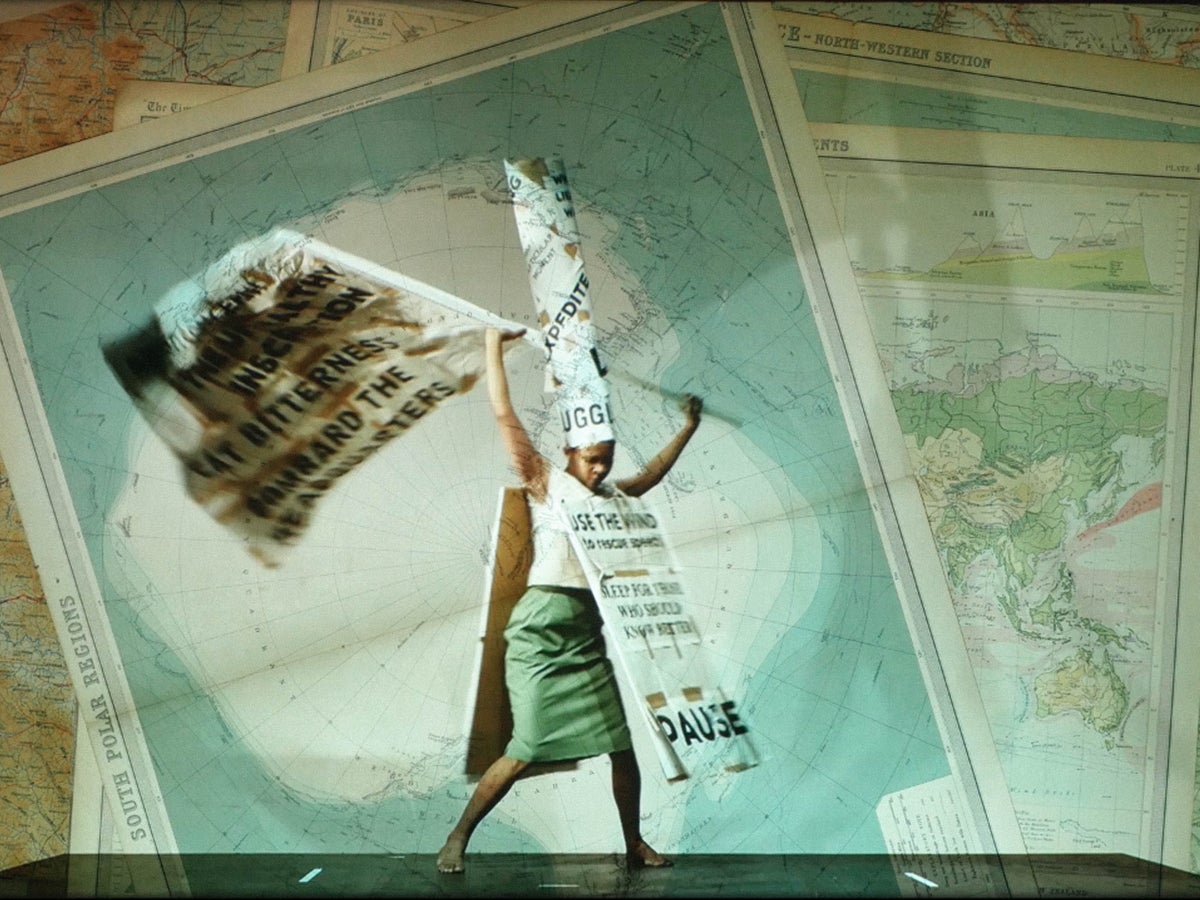

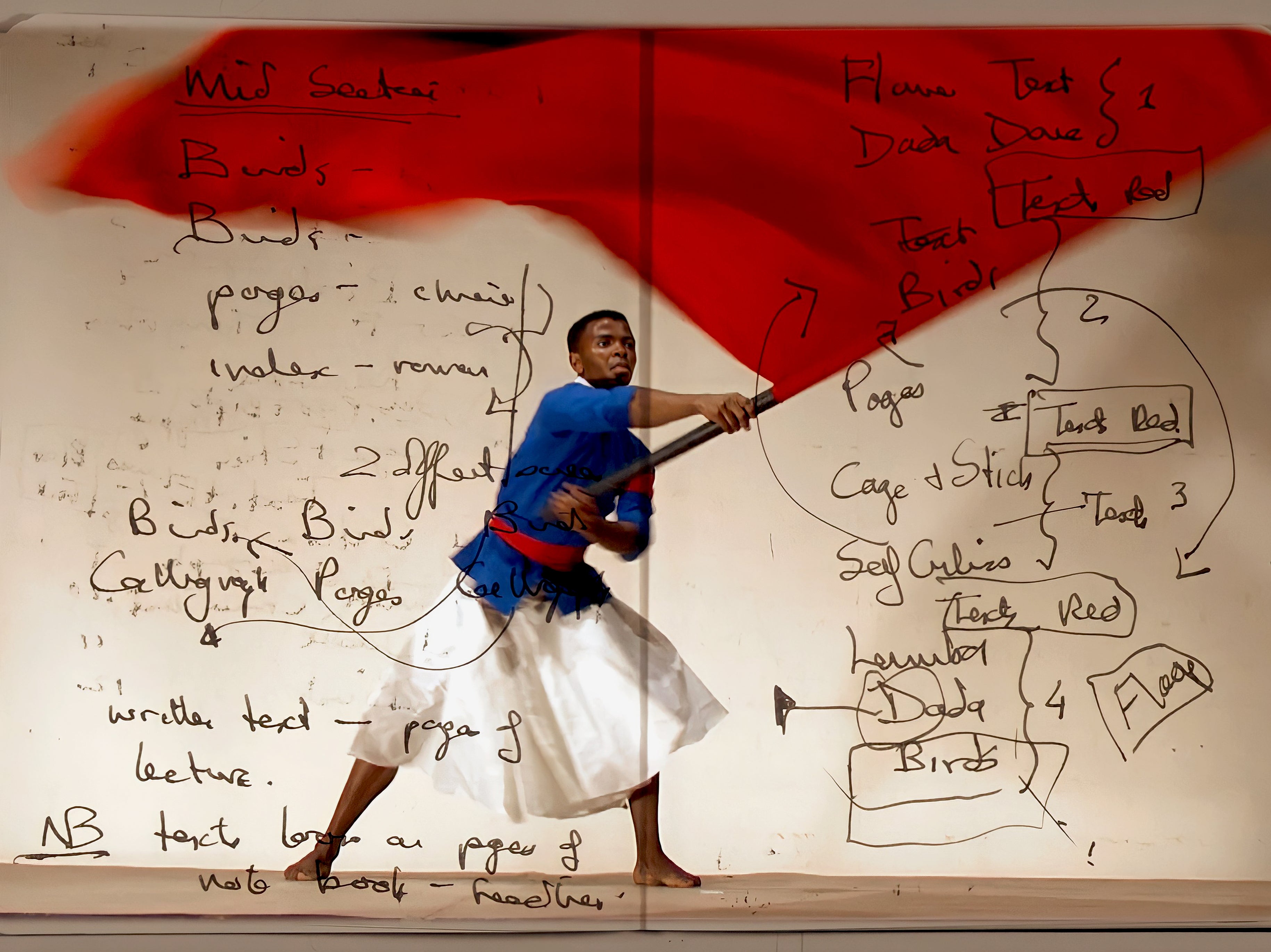

Two rooms of large brush and ink paintings, one of vases of flowers, the other of trees in the veldt, demonstrate Kentridge’s skills in creating seductive monochrome textures, but don’t convince as significant works of art. The addition of faux-profound inscriptions such as Oh to Believe in Another World and A Bird Shall Carry the Voice simply compound their slightness. Kentridge is at heart a collagist rather than a painter. He’s at his strongest when intercutting his painted and graphic work, often extremely cleverly, with other media. Notes Towards a Model Opera (2015), a three-screen video, offers most of the best of Kentridge in just over 11 minutes. The content feels a bit of a muddle: addressing the human disasters of Mao-Tse Tung’s revolutionary China from an African perspective, with reference to China’s current economic ambitions across the continent. But the crackling, rapid-fire layering of media across the three screens keeps you entranced. Pages from old Chinese books, maps, bits of Kentridge’s own sketchbook buzz and flash, with Chinese calligraphy morphing into birds that resemble Picasso’s doves, but reference the tragicomic role of sparrows in Mao’s mad schemes. Live action dancers move through it all wielding flags, climbing out of dustbins and performing teetering ballet steps.

The presence of the human figure, even if only on film, provides the animating factor. A similar array of elements are presented in the final room in relation to a 2019 dance drama called Waiting for the Sybil. But while the production looks astonishing in photographs in the catalogue, the design elements, presented in isolation from the performers, look merely decorative.

Kentridge’s art is best understood in relation to performance – understandably, given those beginnings as an actor and director. There’s something theatrical even in his early drawings and the way they were translated into film. It’s no surprise that he’s had a successful side-career as a designer and director of operas. This show does him a considerable disservice by underplaying this aspect of his art in a misguided attempt to make him appear more the “serious artist”. This large exhibition feels a shade overstretched in these very large spaces, where it could have been brimming with life.

Royal Academy, from 24 September to 11 December