Kyiv, Ukraine – The Azovstal steelworks has become an almost mythical symbol of Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s aggression.

Bird’s-eye view footage from drones, along with photos by Azov Regiment soldiers holed up in the industrial complex in the southern city of Mariupol for 82 days, showed how Russian bombers, multiple rocket launchers and heavy artillery methodically and mercilessly annihilated Azovstal.

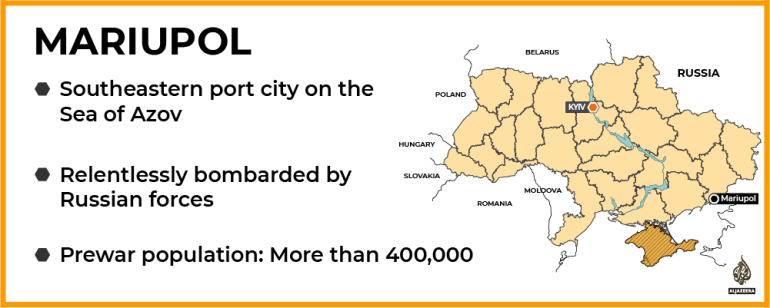

The plant occupied 11 square kilometres (four square miles), provided tens of thousands of jobs, churned out two-fifths of Ukraine’s steel and had its own port on the Sea of Azov to ship metal slabs worldwide.

The odorous smog from Azovstal and its smaller sibling, the Ilich steel plant, blanketed the city of 480,000 people for decades.

In the 1930s, Moscow boosted steel production in Ukraine – and made its steelworkers and coal miners the poster boys of the Communist way of life.

Moscow also ordered the construction of bomb shelters and service tunnels under Azovstal in case of war, and this is ultimately where thousands of Azov fighters and civilians hid from the pummelling this year.

And while news reports about Azovstal’s defence were often front page and top of the hour, one name was rarely mentioned – that of its owner.

Azovstal belongs to Metinvest, a group of mining and steel companies controlled by Rinat Akhmetov, the richest and mightiest of Ukraine’s oligarchs.

Oligarchs controls huge business assets and have influence over individual politicians and, in some cases, entire political parties.

At 55, Akhmetov owns Shakhtar Donetsk, a football club, and hundreds of companies in Ukraine, including energy producers, a telecom and a media holding.

He made his fortune after privatising Soviet-era plants and factories at cut-rate prices, mostly in the southeastern Donetsk region that includes Mariupol.

And the Azovstal and Ilich plants were the pillars of his business fiefdom.

On May 26, Akhmetov said he would sue Moscow for between $17bn and $20bn for the destruction and takeover of the plants and his other assets in the areas controlled by Russian forces or Russia-backed separatists.

“We will for sure sue Russia and will demand proper compensation for all losses and lost business,” he told a local news website.

Akhmetov’s office declined Al Jazeera’s interview request for this article.

Although Bloomberg reported that as of mid-June, Akhmetov’s fortune stood at $6.69bn, he reportedly has lost two-fifths of his fortune since the war began.

And Mariupol’s fall may upend his position as Ukraine’s richest oligarch, some observers say.

“Economically, he’s no longer an oligarch,” Kyiv-based analyst Aleksey Kushch told Al Jazeera.

But others disagree.

According to Vadim Karasev, a Kyiv-based economist, Akhmetov’s assets are diversified and stable enough to compensate for the loss of the metallurgical assets.

“Even with such losses, he will remain the richest and resourceful Ukrainian national,” he told Al Jazeera.

One thing is certain, however: the fall of Mariupol changes the ways Akhmetov and his backers are seen in Ukraine

“The city itself has for eight years been the capital of Akhmetov’s business empire, so there aren’t just financial losses, but political and image-related ones,” Karasev said.

The sad irony is that Akhmetov appears to have fallen on his own sword.

For years, he has thrown his immense financial weight behind politicians from Ukraine’s Russian-speaking, rust-belt southeast that gravitated towards Moscow politically and culturally, Kushch said.

“He reaped the whirlwind,” he said.

Akhmetov’s backing helped propel pro-Moscow politician Viktor Yanukovych to the presidency in 2010 and he served two terms as a politician with Yanukovych’s Party of Regions that a leaked US diplomatic cable once described as a “haven of Donetsk-based mobsters and oligarchs”.

Akhmetov was a key financial backer of Paul Manafort, Donald Trump’s future campaign manager, who helped with the Party of Regions’ political makeover and rebranding.

Akhmetov then went on a shopping spree, buying energy companies throughout Ukraine and diversifying his investments.

By the time Yanukovych fled to Russia in 2014, after the months-long Euromaidan popular protests, Akhmetov controlled most of Ukraine’s power networks.

Many protesters saw Akhmetov as the deposed leader’s “grey cardinal” – and even brought a “blood-stained” Christmas tree to his home in the city of Donetsk.

“I live in Donetsk, and the biggest punishment for me would be the inability to walk on this ground and breathe this air,” Akhmetov reportedly told them.

Within months, he would no longer be able to walk that ground.

Moscow used the political chaos in Ukraine to annex Crimea and back pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk and neighbouring Luhansk.

The rebels seized and “nationalised” Akhmetov’s assets after he refused to pay taxes to the new “authorities”.

Mariupol was one of the cities they took over, but Akhmetov ordered the Azovstal and Ilich plant workers to stand up to the rebels.

Clad in protective uniforms and hard hats, the successors of the Soviet-era poster boys helped Akhmetov’s staunchest critics, the nationalist Azov Regiment, to chase the separatists away.

But bigger problems loomed for him and other oligarchs in Kyiv.

The new, pro-Western government in Kyiv pledged to investigate the privatisation deals that created Ukraine’s oligarchs – along with their alleged corruption.

However, new President Petro Poroshenko, another oligarch who once worked in the government of overthrown Yanukovych, failed to tackle corruption.

Oleh Gladkovsky, Poroshenko’s childhood friend and a former defence official during his leadership, was reported to have run a scheme selling used military equipment smuggled from Russia to Ukraine’s defence ministry.

And it was those reports that largely contributed to Poroshenko’s losing the presidency to comedian and political rookie Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Under Poroshenko, no anti-oligarchic probes resulted in convictions.

But his government outlawed Yanukovych’s Party of Regions, forcing it to morph into smaller parties that competed with each and decimated the clout of pro-Russian forces in the halls of power. The last of them, The Opposition Platform, was banned in early June.

After the conflict in 2014, while an economic shock engulfed the rebel-controlled areas, Akhmetov provided food to “tens of thousands there”.

“Everyone was grateful to him,” Oksana Afenkina, a Donetsk resident who fled for Kyiv in 2020, told Al Jazeera.

However, the tide of public opinion changed pretty soon.

“Since 2017, 2018 they started saying that he surrendered the city, chose not to fight for it,” she said.

Akhmetov is not the only Ukrainian oligarch to lose his assets, turf and clout in the war that began on February 24 this year.

The Azot chemical plant in the besieged town of Severodonetsk, where hundreds of Ukrainian servicemen are trying to repel Russian shelling, belongs to a consortium owned by Dmytro Firtash, a natural gas tycoon wanted in the US on corruption charges.

And in April, dozens of Russian cruise missiles destroyed the Kremenchuk oil refinery, Ukraine’s largest, causing a spike in fuel prices and creating long lines at petrol stations. That refinery belonged to oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, who has interests in banking, ferroalloys and media.

Kolomoisky served as governor of the Dnipropetrovsk region that borders Donetsk – and fielded an entire private army that prevented the region’s takeover by separatists in 2014.

Five years later, Kolomoisky’s backing brought Zelenskyy to power, but the two soon fell out when Kolomoisky sought compensation for the nationalised PrivatBank he co-owned, but got nothing.

And then, Zelenskyy declared a war on all oligarchs.

Last year, the Ukrainian president, now usually seen wearing military-style khaki clothes, signed a new “de-oligarchisation” law that defines an “oligarch” as an individual who controls a major monopoly, significant media outlets, has a net worth of more than $90m and participates in “political activities”.

They are subject to restrictions such as a ban on financing political parties and involvement in the privatisation of state property.

They have to account for their earnings, and officials are banned from holding off-the-record meetings with them.

Some 40 individuals were identified as “oligarchs,” and some objected fiercely.

“Oligarchs are those who don’t like Zelenskyy personally, and, of course, Poroshenko tops the list,” the European Solidarity, a party led by the former president, said in a statement at the time.

Poroshenko faces up to 15 years in jail after prosecutors accused him last year of illegally buying coal worth tens of millions of dollars from the Donetsk separatists.

The charges include “high treason,” “financing separatism,” and “establishment of a terrorist organisation”.

Poroshenko admitted he had bought the coal because otherwise “half of Ukraine would have frozen” in the harsh winter of 2014-2015.

Poroshenko did it through the richest pro-Russian Ukrainian – fellow oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk, a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Charged with “high treason”, selling military secrets to Russia, and “looting” natural resources in annexed Crimea, Medvedchuk was arrested in April after fleeing his house arrest.

For his part, Poroshenko is the subject of almost 200 investigations, mostly into corruption, and denies them all as “politically motivated”.

In late May, Poroshenko left Ukraine, saying he would hold talks with European politicians regarding their support for Kyiv while it fights Moscow.

Looking ahead, some observers say the current war with Russia gives Zelenskyy a real chance to win the war against the oligarchs.

“Ukrainian authorities have a real chance to [conclude] what’s been proudly called ‘de-oligarchisation,’,” Igar Tyshkevich, a Kyiv-based expert with the Ukrainian Institute of the Future, told Al Jazeera.

After the war, the oligarchs will likely try to regain their political clout – but they will face another Ukraine.

The number of war veterans has skyrocketed – and their demands for political representation will grow.

Law enforcement agencies have also boosted their clout.

And the oligarch-owned television networks that used to dutifully transmit their agenda now work in the 24/7 “television marathon mode” covering the war.

“All of it will work against the oligarchs,” Tyshkevich said.