The UK’s economy will grow faster than previously thought in 2025, experts have said, in a much-needed boost for chancellor Rachel Reeves.

The country’s economy will grow 1.6 per cent, the fastest out of Europe’s biggest economies and the third fastest in the G7, after Canada and the US, said the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The boost is being heralded by Ms Reeves as the start of her plan to raise living standards and aid growth.

But Ms Reeves has her work cut out, according to economists, following a long period of very low growth for the UK, while government borrowing costs surge.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said: “I think the IMF will have to upgrade their forecast even more for things to significantly improve for the chancellor.”

The slightly sunnier figures come after a very disappointing period for the UK’s economy after it was hit by the pandemic.

UK growth since the end of 2019 has been among the worst of the big, developed economies, trailing Italy, France and Japan, as well as the US, Canada and the eurozone.

During this period, with 2.9 per cent of growth, the UK beat only Germany, which grew 0.1 per cent. The US stormed away with 11.5 per cent growth.

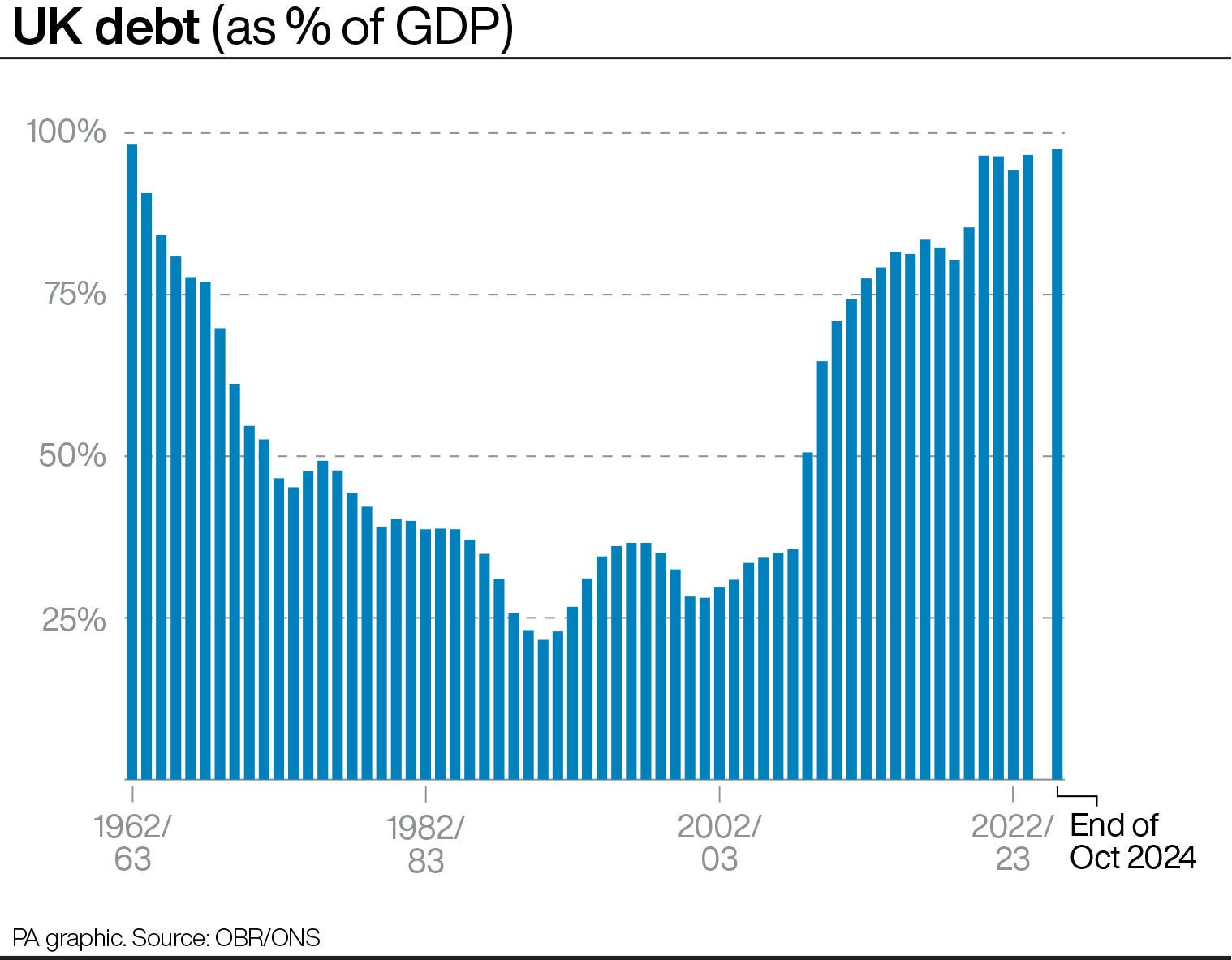

At the same time, borrowing costs have been rising, which means the government must pay more to service its £2.8 trillion of total debt.

On 10-year bonds, the Treasury must offer returns of about 4.63 per cent, compared to 3.94 per cent a year ago. Higher yields will mean paying more than the £3bn a month the UK currently pays.

If the Treasury is going to pay for the interest on this debt, and maybe start to bring the total figure down without raising taxes or cutting services, it needs the economy to expand so that the government’s cut expands too.

“The growth issue is still there,” said Mr Dales.

The economy had been expanding up until the 2008 financial crisis as the government and businesses invested in roads, railways, computers, robots and other hardware which made jobs quicker, cheaper and simpler.

But since the credit crunch, which was followed by a period of austerity in the UK, productivity has only improved marginally. Between 1974 and 2008, the UK’s productivity grew at an average rate of 2.3 per cent a year, and only about 0.5 per cent since then.

Other countries have suffered this phenomenon too, but the UK has been among the worst hit.

The renowned economist Paul Krugman said: “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

Mr Dales says that the main problem is “there has not been enough investment”.

This is in everything from housing to businesses investing in the newest machinery. He said political stability will help attract some investment to help the UK’s productivity grow again.

One estimate suggests that Britain’s productivity lag has cost it £274bn in lost tax revenues, as a bigger economy means more profits to tax.