Noront Resources Ltd. — the company at the heart of Ontario’s embattled Ring of Fire mining development — is once again making headlines as the subject of competing corporate takeover bids by mining giant BHP Billiton and Australian private investment firm Wyloo Metals.

The bidding war has caused Noront’s share price to jump 235 per cent to its highest level since 2011.

Alongside share prices, Indigenous opposition has also ratcheted up, raising significant questions about the viability of the proposed mining operations and the value of Noront’s assets.

The Neskantaga First Nation and the Mushkegowuk council, representing seven affected First Nations, are openly contesting the scale and pace of mine development in their territories. They are in the company of other First Nations throughout the region that have for years asserted their political and territorial authority in the face of Noront’s proposed plans.

Read more: Mining push continues despite water crisis in Neskantaga First Nation and Ontario’s Ring of Fire

Asserting jurisdiction

Indigenous jurisdiction and its denial by authorities have had a huge impact on Noront’s fortunes. Development of the company’s flagship mine has been stalled since 2011, as has the 300-kilometre all-season industrial road — dubbed the “road to nowhere” due to its dubious economic prospects — that’s needed to access the remote mining region.

This is because the region’s First Nations have consistently demanded Ontario recognize their jurisdiction over their lands and territories. The Matawa Nations, including Neskantaga, initially forced the province to negotiate a shared regional approach to decision-making.

That so-called Regional Framework Agreement stopped the province from unilaterally sanctioning development on Indigenous land, but was ultimately dissolved by the province in 2019.

Indigenous authorities have since continued to assert their jurisdiction in the region. Most recently, a coalition of three First Nations (Attawapiskat, Fort Albany and Neskantaga) are insisting that a newly established regional assessment of the cumulative impacts of proposed mine and road developments is Indigenous-led.

Read more: Ottawa steps into 'Ring of Fire' debate with Doug Ford

Throughout this period, Noront shares have plummeted from nearly $2 at the start of 2010 to less than 20 cents since 2019. The company’s debt has increased by at least $100 million since 2013 to $299 million as of Dec. 31, 2020 and its outstanding loans stand at $51.4 million.

Despite mounting evidence that the value of the company and its assets require Indigenous consent, federal and provincial governments have continued to pour hundreds of millions of dollars into mining developments in the Ring of Fire in the form of exploration financing and infrastructure support.

Millions for exploration

As approval processes have dragged on and then stalled, Noront — backed by federal and provincial treasuries — has attempted to create value by increasing its assets and expanding its exploration program.

Since December 2008, the company’s regulatory filings show the federal and Ontario governments have subsidized Noront’s Ring of Fire exploration programs to the tune of nearly $45 million through a tax-based mechanism known as flow-through financing.

That mechanism allows firms to raise exploration funds from investors and return tax credits to them.

Additional federal and provincial refundable tax credits are also available to flow-through investors, resulting in the transfer of millions of dollars — money that would have otherwise been tax revenue — to Noront’s exploration of the Ring of Fire. According to the company’s aforementioned regulatory filings, Noront has raised more than $75 million of flow-through financing since 2008 for Ring of Fire properties.

This flow of government money reveals a system of economic relationships described by the Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations-led research centre, as colonial and predatory.

Amid Indigenous demands to determine and control the pace of development in their territories and to create the institutions required to do so, this flow of money also raises serious concerns about the financial realities of the Ring of Fire project.

Circumventing Indigenous jurisdiction

While the province once estimated the cost of implementing the doomed framework agreement to be slightly over $20 million, the cost of circumventing Indigenous jurisdiction is much higher.

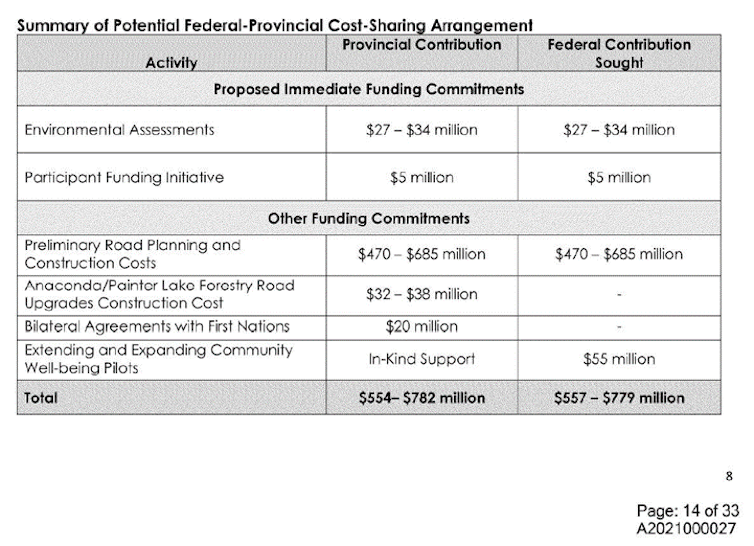

Since tearing up the agreement in 2019 in an attempt to speed up development, Ontario has entered into bilateral funding agreements worth $20 million with two First Nations currently serving as proponents of the all-season road.

According to documents obtained though an Access to Information request, it’s also currently negotiating a planning agreement worth $38 million with another First Nation.

These same documents reveal the federal government spent approximately $11 million annually since 2016 to fund so-called community well-being projects in five Matawa communities. These are programs purportedly aimed at improving “community readiness” for mining operations in the Ring of Fire.

If Ontario has its way, this funding will be renewed at a total of $55 million over five years. Between 2010 and 2015, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada contributed nearly $16 million through the strategic partnership initiative to “support First Nations mining readiness activities” in the area, an investment topped up by a few million in 2016.

It also contributed $255 million over two years to a First Nations fund partially earmarked to support regional infrastructure in the Ring of Fire and intended to encourage compliance with mining projects.

A 2019 intergovernmental memo — also obtained via the Freedom of Information request — shows the federal government also offered to “explore options to advance Ring of Fire projects” using money that was designated for well-being projects in Indigenous communities.

There’s also the matter of the $1.6 billion all-season road. Ontario has promised to fund the road through the homelands of multiple First Nations, most recently through a proposed cost-share arrangement with Ottawa.

Debt, debt and more debt

Noront has consistently under-represented to investors, and now to corporate suitors, the legal and financial liabilities associated with Indigenous jurisdiction — and there are many.

Regardless of who successfully bids for the company, opposition to the Ring of Fire project is only likely to increase unless First Nations are empowered to exercise real control over the decisions that will impact them. This raises the spectre of litigation, Indigenous land defence actions — and more debt.

According to the internal documents, the federal and provincial government are expecting to earn $4.4 billion in combined tax revenues during the first 10 years of the proposed mine’s operation. But if they add up the amount of money they’ve already paid to defy and circumvent Indigenous jurisdiction, and the financial costs associated with continuing to do so, that $4.4 billion will soon be exhausted.

It is entirely likely that any profits related to this enterprise have already been spent. The question that remains is who will be left holding the debt?

Anna Stanley receives funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.