It appears that China has moved up its agenda for bringing Mars samples to Earth, and aims to do so before the U.S. achieves this same goal.

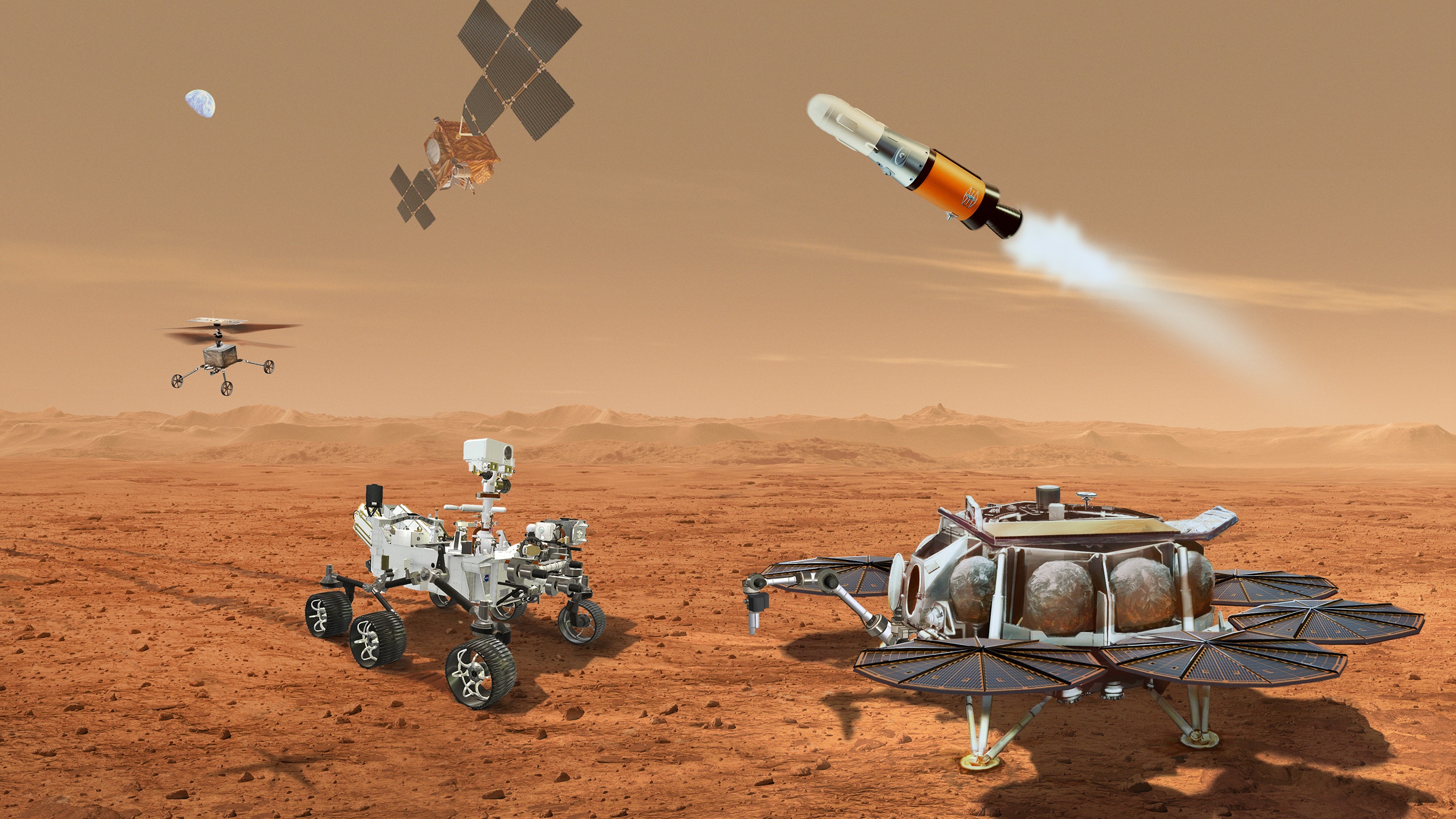

NASA's Mars sample return plan, a joint effort with the European Space Agency (ESA), continues to be scrutinized. A newly launched strategy review team will advise agency leadership about what to do now and offer recommendations by year's end, or early next year.

The hoped-for bottom line outcome is for a fingers-crossed, NASA-blessed blueprint for the Red Planet, one that offers the highest chance of getting Mars samples to Earth before 2040, and doing so for less than $11 billion.

Meanwhile, China is on an earlier flight path to achieve what scientists call the "holy grail" of Mars exploration.

Space.com took the pulse of several leading Mars researchers for their thoughts, concerns and aspirations about the two sample-return efforts.

Related: NASA wants new ideas for its troubled Mars Sample Return mission

China plan

First of all, a bit of background.

China's second International Deep Space Exploration Conference, hosted by the country's Deep Space Exploration Laboratory was held in September in Huangshan City, in Anhui Province.

During that multi-day gathering attended by hundreds of international guests and domestic experts, Liu Jizhong, chief designer of the Mars sample-return project, said that China now plans to launch its Tianwen-3 mission around 2028 — two years earlier than previously scheduled — and haul Mars samples to Earth that same year.

"It will take two launches to carry out the Mars sample-return mission due to the limited carrying capacities of our current rockets. Two Long March-5 carrier rockets will be used for the mission," Liu told the state-run Xinhua news agency in an interview.

Related: China moves Mars sample-return launch up 2 years, to 2028

Shoot and ship

The quest to bring pieces of Mars to Earth draws upon China's lunar sample-return efforts, performed by two different missions — the Chang'e 5 near-side mission in December 2020 and Chang'e 6, which delivered far-side samples to Earth in June of this year.

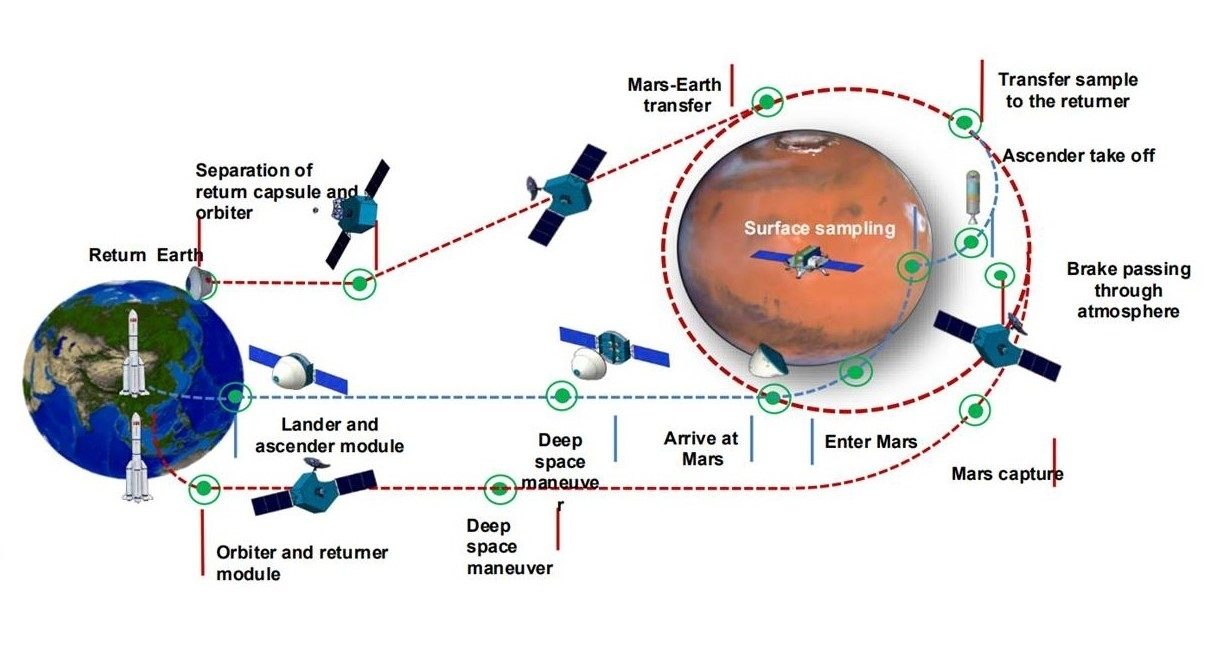

Similarly, Tianwen 3's planned mission profile involves collecting samples on the Martian surface, launch, rendezvous and docking in Mars orbit, followed by rocketing the gathered goodies to Earth.

The lander architecture parallels that of Chang'e 5 and Chang'e 6, both of which featured a scoop and a drill. Also being appraised are mobility aids to retrieve nearby samples at the touchdown zone.

The scientific driver for Tianwen 3 is the search for signs of Mars life. Chinese space specialists say the mission will involve international cooperation, international payloads, sharing of samples and data, and joint planning for future missions.

Related: Life on Mars: Exploration & evidence

Lay of the land

As for candidate Tianwen 3 landing spots on the Red Planet, "engineering constraints do not respect national boundaries," said James Head, a leading planetary scientist at Brown University in Rhode Island.

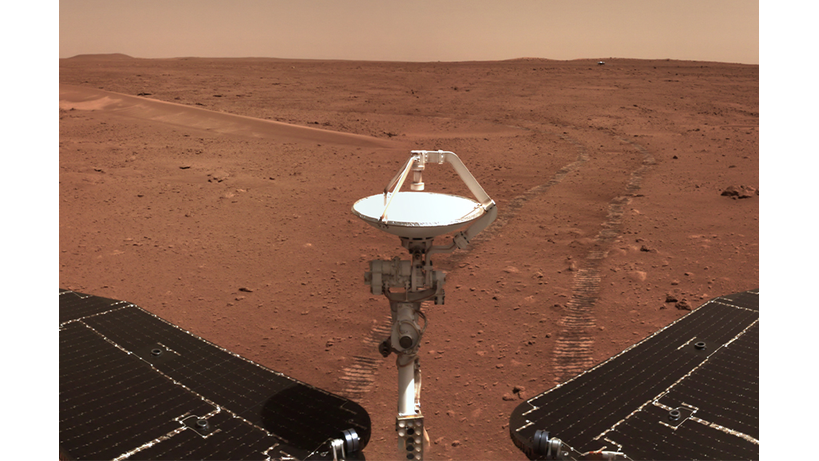

Head underscored China's successful Tianwen 1 Mars mission, which delivered an orbiter, lander and rover to the Red Planet in 2021. This independent effort performed a soft landing, and then deployed the Zhurong rover to reconnoiter Utopia Planitia, a huge impact basin on that distant world.

"I don't think that China has finally decided on the whereabouts of their Mars sample spot, but my bet would be Utopia," Head told Space.com. China has already been there successfully, he said, and the country's scientists therefore know the lay of the land, as well as the area's geology.

Related: China might add a helicopter and 6-legged robot to Mars sample-return mission

Politics of science

In some ways, China's foray into Mars sample return could be viewed as a more political issue than a scientific one.

Scott Hubbard is an adjunct professor in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stanford University. He and Mars have a long-term relationship:

Hubbard was NASA's first-ever Mars program director and the architect of Red planet missions from the Mars Odyssey orbiter to the Curiosity rover, which is still on the prowl on the Red Planet at Gale Crater.

"If, as has been reported, China successfully executes even a 'grab sample' at Mars and returns it safely to Earth before the U.S., that would constitute a 'Sputnik Moment,'" said Hubbard, referring to the former Soviet Union's scientific and political coup in lofting the first satellite into Earth orbit.

A grab sample, Hubbard added, is material scooped up by a stationary lander — whatever samples are within arm's reach.

"A grab sample, unless the Chinese were lucky, would have less scientific value than the carefully selected cores being collected by NASA's Perseverance rover," now busily at work on Mars at Jezero Crater, Hubbard said. "But my sense is that the performative and political power of a ‘China beats U.S.' headline is far more important to the People's Republic of China."

Hubbard pointed to the result of NASA's original planning, a 20-year campaign of orbiters, rovers and landers that have produced a wealth of scientific data and new technology. That effort, he said, also resulted in the selection of Jezero Crater and nearby highlands as an excellent place to pick samples for Earth return and detailed examination.

The gift that keeps on giving

NASA has dominated the exploration of Mars, said Harry McSween of the University of Tennessee's Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, "and after doing so much planning and effort in Mars sample return, it would be distressing if the U.S. and our European partners don't bring back the first samples."

Getting those long-distance Mars samples into well-instrumented labs here on Earth is indispensable, said McSween.

"Our experience with lunar samples returned by Apollo demonstrates that samples can revolutionize our understanding, and they are the gift that keeps on giving, as new ways of analyzing materials can be brought to bear many decades later," he said.

"Returning Mars samples is the next giant step in planetary exploration. It's challenging and costly, but also inspiring and an engaging part of our national posture," McSween said.

Bridge too far?

Noted Mars expert Chris McKay, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, flagged a 2002 approach that advocated astrobiology research on Mars with what was termed a "groundbreaker" sample return mission. That proposal featured a simple "Step 1" Mars lander whose only tools were an extendable arm with very simple sampling devices.

"If we had followed this approach, we'd [already] have samples from Mars here on Earth," McKay said.

"Note that this is very similar to the approach that the Chinese used in their lunar far side sample return," McKay added. "Instead of this simple first step, NASA chose to reach for a more complex first sample return that is, as we now see, a bridge too far. Is it too late to go back to a simple Step 1?"

Here's the scoop

In regards to China taking a front seat on Mars sample return, that prospect is bittersweet, responded Pascal Lee, a planetary scientist with the SETI Institute in California, as well as the nearby Mars Institute situated at the Ames Research Center.

"As a scientist, my thoughts are 'Yay…that's great! More samples from Mars, and sooner the better!' But from a space strategy standpoint, this would be yet another wakeup call, if not a blow," Lee said.

By returning samples from Mars, China would become the first nation to achieve the roundtrip voyage between Earth and Mars, Lee pointed out.

"The next step would be a human mission to Mars. For NASA, there's more than just 'getting samples back first' at stake. It goes straight to our ability to lead the exploration of Mars by humans, which includes returning them safely to Earth," Lee said.

Hubbard voiced a similar frustration.

"What should exasperate everyone is for the Chinese to use our 20 years and $12 billion of NASA and European Space Agency mission knowledge, our published technology and peer-reviewed science in order to scoop the free world," said Hubbard.

"Taxpayers both in the U.S. and Europe should be righteously angry at Congress, NASA and ESA for not appropriating the funds and designing the projects necessary to hold to the original return date," Hubbard concluded.