SpaceX's Starship megarocket may come into its own in 2025.

The 400-foot-tall (122 meters) Starship is the biggest and most powerful rocket system ever built, and it's designed to be fully and rapidly reusable. SpaceX believes this combination of brawn and efficiency is the key breakthrough that will allow humanity to achieve a variety of spaceflight feats — including the settlement of Mars, a long-held dream of company founder and CEO Elon Musk.

That vision may become clearer over the next 12 months or so, for Starship appears poised to make a big leap in 2025.

Ramping up the flight rate

Starship has launched six times to date — twice in 2023 and four times in 2024.

The vehicle made a lot of progress on these test flights, all of which flew from SpaceX's Starbase site in South Texas. On the most recent three, for instance, both Starship elements — the Super Heavy booster and the 165-foot-tall (50 m) upper-stage spacecraft, known as Starship or simply Ship — survived the downward trip through Earth's atmosphere in one piece.

Related: What's next for SpaceX's Starship after its successful 6th test flight?

And on Flight 5, which launched on Oct. 13, Starbase's launch tower plucked the returning Super Heavy out of the air with its "chopstick" arms, demonstrating the recovery strategy that SpaceX plans to employ for both Starship stages on operational missions.

Such tower catches could become a relatively common sight in 2025. SpaceX has applied to increase the number of permitted Starship liftoffs from Starbase fivefold in the coming year, to 25 — and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has given its preliminary blessing.

A draft environmental assessment released by the FAA in November approves not just the 25 Starship launches from Starbase but 50 tower catches at the site as well — 25 of Super Heavy and 25 of Ship. SpaceX also already has an FAA license for the Starship Flight 7 launch, which could occur in early to mid-January.

Such a surge would be huge for SpaceX, whose rocket-development strategy centers on flying, iterating and then flying again. And there's no reason to think that goal is out of reach; after all, the company has launched more than 130 orbital missions in 2024, the vast majority of them with its workhorse Falcon 9 rocket.

"You don't have to be a rocket scientist to understand that the schedule they work by is unprecedented," astrophysicist Ehud Behar, a professor at the Technion — Israel Institute of Technology, told Space.com.

And 25 Starship flights per year is far from the horizon goal; the company plans to continue ramping up the rate in 2026 and beyond.

"Elon would say, next year he would love to have us have 25 missions a year, and in the next few years, 100,” Kathy Lueders, general manager of SpaceX’s Starbase operations, said in November during the Mexico Space Agency’s National Congress of Space Activities conference, according to Gizmodo. "He was telling me, ‘Kathy, I would love to launch a couple of times a day.'"

Not all of these future missions will fly from Starbase: SpaceX also plans to launch Starship from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, which already hosts liftoffs of the company's Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets.

Crewed flights coming

SpaceX already has some customers lined up for Starship, chief among them NASA, which tapped the megarocket to be the first crewed lander for its Artemis program of moon exploration.

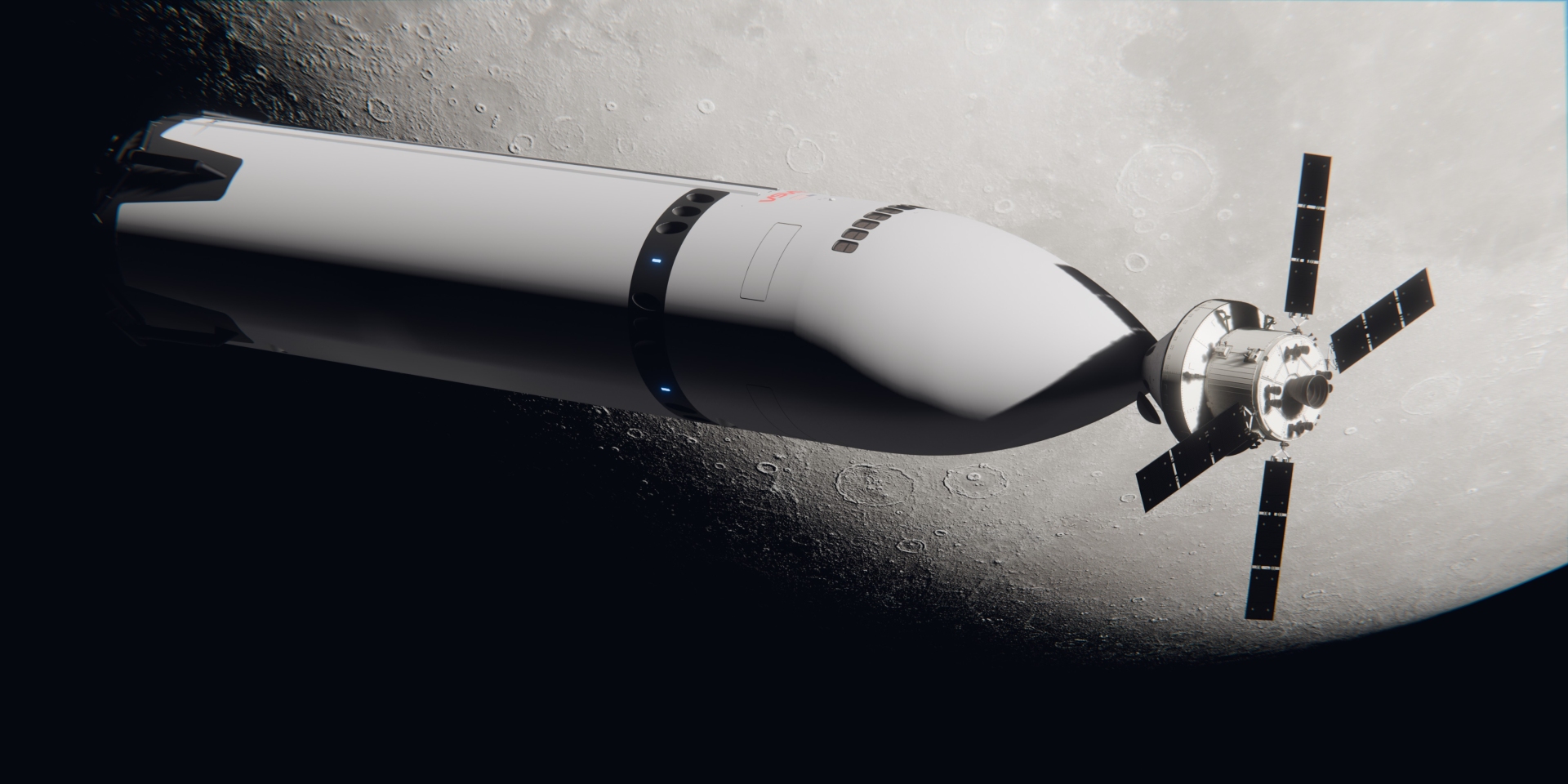

If all goes according to plan, Starship's upper stage will put NASA astronauts down near the moon's south pole on the Artemis 3 mission, which is currently slated to lift off in mid-2027.

That schedule has been pushed back multiple times, most recently due to issues with NASA's Orion crew capsule. (The Artemis 3 plan calls for astronauts to leave Earth aboard Orion, using NASA's Space Launch System rocket. In lunar orbit, Orion will meet up with a modified Starship upper stage, which will carry the astronauts down to the moon's surface.)

It's unclear if Artemis 3 will be ready to fly in 2027, Behar said, given NASA's budget constraints and the overall difficulty of crewed missions, especially when they involve a brand-new spaceflight system. (How many successful uncrewed Starship flights will NASA want to see before putting its astronauts on the vehicle?)

But he's confident that Starship will be ready to perform more prosaic spaceflight roles by then.

"I think Starship, as a launcher of satellites, seems to be on track," Behar said. "I don't see a reason why they won't be on schedule."

Related: NASA's Artemis program: Everything you need to know

Bigger rocket, bigger demand?

Starship will get even bigger and more powerful over time, according to SpaceX.

"With a few planned upgrades, Starship will have three times the thrust [at liftoff] of Saturn V at 10,000 metric tons of thrust, plus the added benefit of full reusability," SpaceX manufacturing engineering manager Jessica Anderson said during the webcast of Starship's sixth test flight, which occurred on Nov. 19.

"Starship 2 will be capable of carrying more than 100 tons to orbit, and Starship 3 will be able to lift more than 200 tons to orbit," she added. "The amount of mass we're able to launch per rocket is crucial to creating a self-sustaining city on Mars."

Because Starship is fully reusable, the vehicle could eventually deliver such power numbers for just $2 million to $3 million per flight, Musk has said. That would be incredibly cheap; SpaceX currently sells Falcon 9 missions for about $67 million.

Those anticipated Starship numbers may be tailored toward Mars settlement, but the megarocket could end up flying a lot of missions closer to home as well. SpaceX plans to finish assembling its Starlink broadband megaconstellation using Starship, and variety of customers will likely find ways to take advantage of the vehicle as well, Behar said.

"I think we've learned the lesson that, if technology is developed and affordable, there will be uses for it," he said.

"People forget that space is a place; it's not really one thing," Behar added. "There are a lot of things you can do in space, going from developing new materials to developing medicine. Right now, the threshold just to get there is very expensive."