The wildfires in the Los Angeles area have destroyed thousands of structures, many of them homes, and firefighters continue to battle the infernos. Parts of Pacific Palisades, Altadena, Pasadena and other California communities are now unrecognizable.

As evacuation orders are lifted, safe drinking water should be top of mind for those residents able to return to their homes.

What many people don’t realize is the extent to which their community drinking water systems can be damaged by fire, how their water is affected and what they can do about it.

As an environmental engineer, I work with communities affected by wildfires and other disasters. Over the years, my team and I have been called in to help after some of the most destructive wildfires in U.S. history. In some cases, we have advised state and local officials from afar.

Several local water systems in the Los Angeles area have begun issuing warnings about not using the potentially unsafe drinking water. Here’s what residents in the area, and anyone else living near where a wildfire burns, need to know.

How fires can make water unsafe

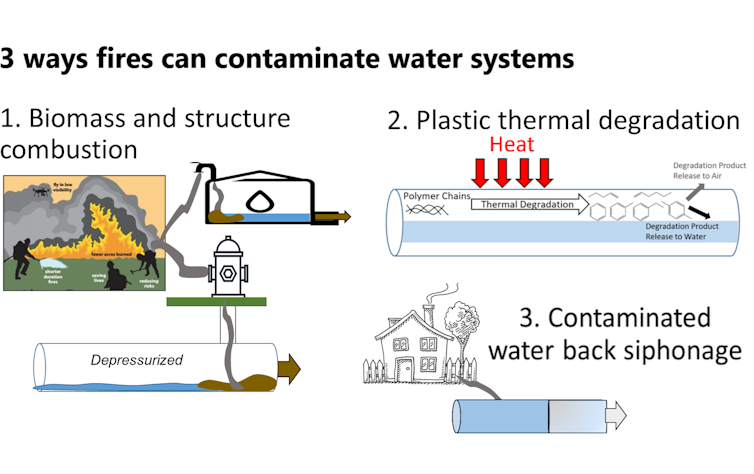

Fires can make drinking water, and the water pipes and tanks themselves, unsafe. This occurs for a number of reasons.

One cause is when high water use from firefighting drains the water system.

Water systems are not designed to fight wildfires. Damaged and destroyed structures also prompt uncontrolled water leaks. Power loss also prevents water from being replenished fast enough into the draining water systems. Combined, these factors can depressurize the water system, leaving no water available.

When water is depleted, the system is vulnerable to chemical contamination.

Drinking water contamination can also come from the air and from damage to water system infrastructure. Heat can partially melt plastic pipes and water meters, releasing chemicals; smoke can be sucked into water systems; and breaks in the water infrastructure can introduce contamination.

A host of cancer-causing chemicals have been found in damaged water systems after wildfires. Sometimes these chemicals, such as benzene, can cause someone to become immediately ill if they drink or use the water. Symptoms can include nausea, headaches and rashes.

These chemicals stick to the infrastructure surfaces and can even penetrate some plastic pipes and gaskets. Removing them can take days to months. Some plastics can adsorb chemicals like a sponge and release them into clean drinking water slowly, making that water unsafe for long periods of time.

How communities can reduce the risk

Residents and businesses should pay attention to announcements from their drinking water provider and health officials about water safety.

Safety can be determined through proper chemical testing. Fortunately, the first-ever guide for water systems to respond to and recover from fires was published in 2024. Property owners can find more information from groups like our research team at Purdue University.

When to test and treat your own water

When it comes to testing home drinking water, caution is needed.

After the 2023 wildfires in Maui, Hawaii, and the 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California, I met with many households who spent hundreds to thousands of dollars to hire companies to conduct their own water testing. However, many of the results turned out to be irrelevant. In some cases:

- Residents were charged for water analysis even though their samples were improperly handled.

- The potentially contaminated water was dumped out of plumbing before a sample was collected.

- Water samples were not screened for the correct fire-related chemicals.

- Samples were not collected from the right locations or enough locations in the home.

Treating water is not advised until the levels of contamination are known. Water systems in the area have issued such warnings.

Residents should also be aware that home water treatment devices are not certified to make extremely contaminated water safe.

To help property owners make the best decisions, water utilities need to rapidly test and share with the public what chemicals are present in their water systems. Once that testing has been done and the risks are known, property owners may want to commission their own testing if their plumbing is damaged or if contaminated water has flowed in.

Water systems can recover

It can be frustrating waiting for information, but immediately after fires it’s often unsafe for water officials to enter the affected areas to begin testing.

As history has shown, safe water can be restored. Assistance from experts who have helped others respond can expedite the recovery. In my experience, communities that recover rapidly and stronger are those where they work together and support one another.

Andrew J. Whelton receives funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation, U.S. National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, City of Louisville, Paradise Irrigation District, Paradise Rotary Foundation, the Water Research Foundation, and crowdfunding.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.