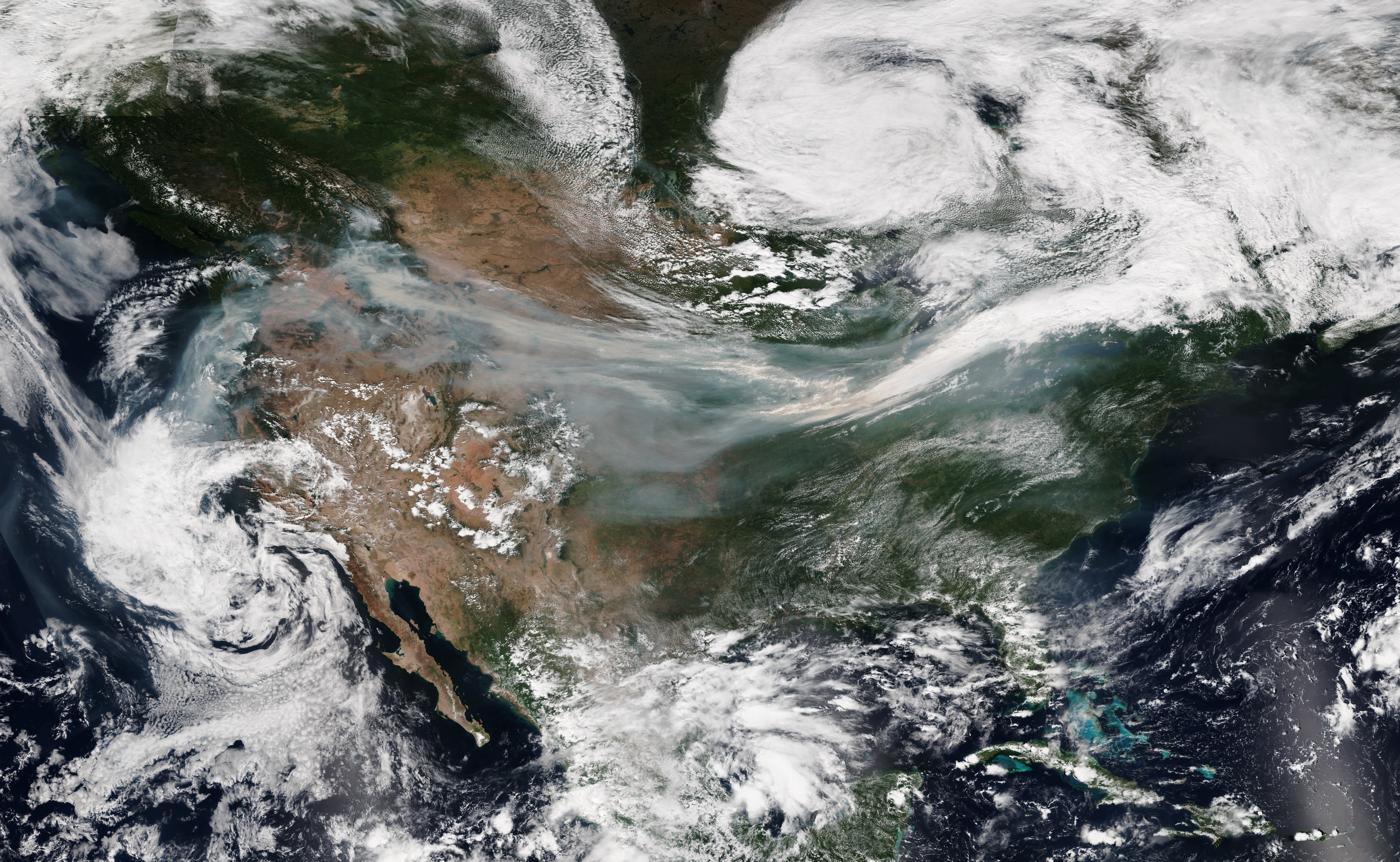

Over the course of just a year smoke from wildfires and prescribed burns across the U.S. caused billions of dollars in damages and tens of thousands of early deaths.

In 2017, when there were dozens of blazes burning across the West, researchers reported this week that the fires resulted in an estimated $200 billion in health damages associated with 20,000 premature deaths.

Several groups were found to be the most harmed, including senior citizens and Black and Native American communities.

“Many studies have found that fire smoke, like other air pollutants, is associated with increased morbidity and mortality risk,” Nicholas Muller, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, said in a statement. “But until recently, the associated social costs were less well understood.”

Mueller is the co-author of the research, which was published Tuesday in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

To reach their conclusions, the authors used a quantitative model to investigate the damages caused by ambient particulate matter produced by the smoke across the contiguous U.S.

Wildfires produce a mix of pollutants and particle pollution, which is also referred to as particulate matter. PM 2.5 is the air pollutant of greatest concern to public health from wildfire smoke. It can travel deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream.

The health effects of this pollution can range from eye and throat irritation to heart failure and premature death. It may impact the body’s ability to remove viruses or bacteria from the lungs. Even short-term exposures are linked to increased risk of exacerbation of pre-existing respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

While wildfire smoke can make anyone sick, some people are at increased risk. Those people include women who are pregnant, children, first responders, older adults, outdoor workers, people of low socio-economic status, and people with asthma, respiratory diseases, or cardiovascular disease.

Any long-term exposure is statistically associated with an increased risk of mortality, the researchers noted.

While nearly half of the damage came from western wildfires that year, the remainder came from southeastern burns. Roughly half of the premature deaths were due to wildfire smoke and burns, respectively.

With fires increasing in intensity and severity due to climate change, the study authors said that expanding air quality monitoring, investing in filtration technologies, and passing out N95 masks and other protections could help protect vulnerable populations.

Prescribed burns will notably be a critical tool to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires, although climate change is also resulting in fewer days when they can safely be utilized.

“Our work reveals the extraordinary and disproportionate effects of the growing threat of fire smoke,” said Luke Dennin, a Ph.D. student in engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon, who led the study. The scientists have also provided “suggestions for local, state and national decision-makers and planners addressing the growing environmental hazard of fire smoke, particularly its impact on vulnerable communities,” he added.