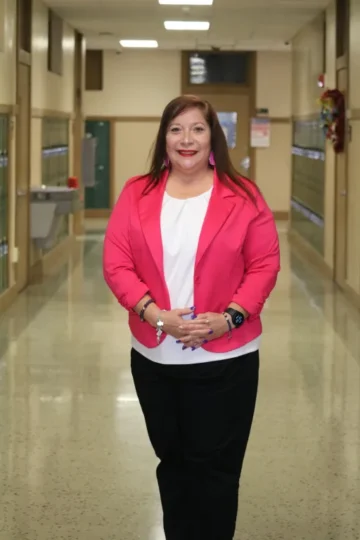

Above: Honor Roll student Timothy Murray displays an award for grand champion of the Brownsville Independent School District Elementary Science Fair in November 2022.

Eleven-year-old Timothy Murray has many trophies displayed in a row by the wall of his room. During a video call, he shows me what he’s won from science projects, chess competitions, and coding programs, and ends with the largest one in his collection—a three-tiered, star-studded trophy he won as grand champion of the Brownsville Independent School District Elementary Science Fair in November 2022. It seems almost as tall as his 4-foot-1-inch frame. He explains that the project measured safety factors when driving over the Golden Gate Bridge by changing variables of speed, mass, and the size of a vehicle.

It’s hard for me to keep up as Timothy speaks and gestures excitedly at his project’s colorful tri-fold board.

The project was the last one Timothy worked on with his father before his father died in April from multiple myeloma, a form of blood cancer. His dad had been sick since Timothy was two, and family outings were often trips to the hospital. As his cancer spread, Timothy’s dad never tried to hide his sickness. Rather, he demystified the disease, explaining the causes and the symptoms, and preparing Timothy for his possible death.

Timothy says that because of his father, he wants to be an oncologist when he grows up, although his mom laughs about how everyone else thinks her son should be a lawyer since he likes to argue so much. His father taught him how to speak up and advocate for himself.

“My dad taught me what is wrong and right. Do this. Don’t do that. Finish projects as soon as I can. Because if I’m late, it can hurt my grades,” Timothy said. “My grades are very fragile right now: I have an 84 in spelling, the rest are in the 90s.”

But Timothy’s efforts to speak out and request counseling for himself at the start of his fifth-grade school year at Palm Grove Elementary School led to what the family calls retaliation by Palm Grove Elementary School Principal Myrta Garza.

On September 8, school administrators told Timothy—who had irked the principal with requests for counseling and for clarification on school dress code policies—that another student alleged that he made threats against Garza. Timothy denied the allegation, but Garza called law enforcement, who detained him and placed him in solitary confinement for three days at the Darrell B. Hester Juvenile Detention Center in Brownsville.

Cameron County prosecutors pushed for Class C felony charges of “terroristic threat” and argued for two more weeks of detention. Instead, Judge Adela Kowalski-Garza ordered a safety risk evaluation and conditional release home until his hearing November 8.

Juvenile justice experts interviewed by the Texas Observer say the Brownsville Independent School District and police seem to have violated state laws and other rules in Timothy’s case that are intended to protect such young children from excessive law enforcement actions. These include a law that requires a school to undergo a fact-based, systemic threat assessment involving the parent to determine if there is an imminent threat warranting a referral to law enforcement and a Texas Supreme Court order that prohibits the handcuffing and shackling of young children. State law allows a minor to be placed in solitary confinement for 24 hours; staff at the detention center told Rincon her son was further isolated for COVID precautions.

“This was the choice of the school to refer to law enforcement, the choice of the law enforcement to detain the child, the choice of the prosecutor to charge him and try to trump up the charges,” said Renuka Rege, policy advisor at Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit that researches and advocates on many issues, including juvenile justice. “All of these things are failures in serving young kids.”

The Observer requested comment and information from Brownsville ISD Superintendent René Gutiérrez, district Police Chief Oscar Garcia, and Garza. We asked the district if officials had conducted a threat assessment, but the only response we received was from Director of Public Relations and Community Engagement Jason Moody, who wrote, “This case has been transferred to the Cameron County Juvenile Justice Department and is pending adjudication. Brownsville ISD cannot comment any further on this matter.”

Palm Grove Elementary School is a squat, tan building just five miles from the U.S.-Mexico border. There’s not much development surrounding the school in this semi-rural neighborhood of Brownsville. His mother, Nadia Rincon, moved her family there in 2020 after they could no longer afford housing in more-expensive Uvalde given growing medical expenses for Timothy’s father.

As a fourth grader at Palm Grove, Timothy came to rely on the support of a school counselor. According to Rincon, the counselor had guided him through his dad’s passing and encouraged him to continue working hard in order to get into the district’s gifted and talented program. So he was troubled when he didn’t see her, or any other counselor, as he started his fifth-grade year at the school in August.

“I didn’t know she had left. So I was kind of confused and I asked the principal where she was. She didn’t seem like she liked that. She just told me, ‘I’m in charge,’” Timothy said. He pressed the issue and told Garza that the school needed to have a counselor. “Then, she kind of pushed me aside.”

He later found out the counselor had moved to another school.

Timothy said that afterward, he felt like he was being picked on because Garza repeatedly admonished him. First for his haircut. And then for not wearing a school uniform—a rule that had not been enforced the prior year. There is no dress code policy posted on the school’s website and most photos show students not wearing uniforms. Timothy wrote three handwritten letters to Garza asking her to clarify if wearing the uniform was a school recommendation or policy. Garza never responded but, according to Timothy, would stand outside of his classroom or in the lunchroom to yell, “Uniform, Murray!”

“There would be kids behind me without uniforms, but they didn’t get screamed at,” Timothy said. “She would tell me, ‘Where’s your uniform? Otherwise, we’re going to kick you out of the ACE [afterschool] program, revoke your library privileges, revoke your lunch privileges.’”

Garza comes from a Brownsville education legacy. Her mother, Rachel Medina Ayala, was one of Brownsville Independent School District’s first female superintendents. Garza’s two sisters are also principals in the district.

“They all say, ‘You’re just like your mom; you’re following in her footsteps,’” Garza told the Brownsville Herald in 2021.

Patrick Hammes, organizer for the Brownsville Educators Stand Together union, was a special education teacher when Ayala served as a deputy superintendent in the district. Hammes remembers her as exacting.

“She ran things with an iron fist. She had her admirers, but there were a lot of people who were afraid of her,” he said. ”Myrta Garza is just like her mother.”

Last summer, the current superintendent, René Gutiérrez, announced a shake-up in the leadership on several campuses. Canales Elementary, where Garza was principal for four years, was targeted as needing improvement, and Garza was reassigned to Palm Grove. The former counselor and principal at Palm Grove were transferred to Canales Elementary School.

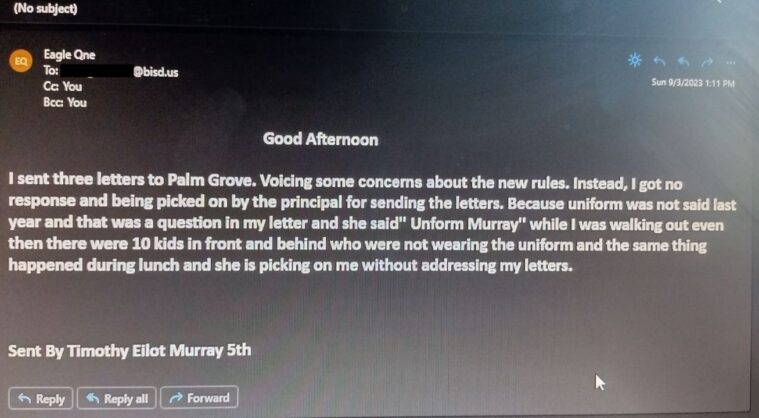

On September 3, Timothy sent an email to Gutiérrez. In the email Rincon shared with the Observer, Timothy writes that Garza “is picking on me without addressing my letters.” Timothy never received a response.

His ordeal began five days later. In the late morning of September 8, Timothy was pulled out of music class and ushered into a room where he found Garza, Assistant Principal Michelle Saucedo, a district police officer, and a counselor sent from the district’s central administrative office. He was told another student had just reported that Timothy said he was planning to kill the principal. Rincon said she was called and rushed to the school but was not allowed to be in the room while Timothy was being questioned.

“When the police officer had his body cam off, they were yelling and telling me, ‘We’re gonna go to the full extent. We’re gonna put you in a lockbox,’” Timothy said. “Then, when the body cam was finally on, they were so nice.”

Timothy told me he had explained to the school and district officials that the accusations were not true, that the only conversation he had that morning was with two other boys about wearing his sweater over his uniform.

Rincon has received only a school conduct referral form, on which administrators wrote that “Timothy told another student that his hair was messy because he was up all night to come up with a plan to kill Mrs. Garza (principal).” Underneath, Timothy wrote: “No I was not up all night I just forgot [to comb my hair].”

On the bottom of the form, administrators had written: “OSS [out-of-school suspension] 3 days 9/11-9/13.”

But instead of suspension, Garza summoned a police officer to arrest Timothy at school. In a video that Rincon shared with the Observer, Timothy puts his arms up on a wooden shelf and waits to be handcuffed as directed by a police officer. Wide-eyed and silent, he looks at his mom, who says, “My son wrote a letter to the school principal because she was retaliating against him, and now he is getting arrested.”

Timothy was brought to the Darrell B. Hester Juvenile Detention Center and put in solitary confinement for COVID precautions to await his hearing on Monday. Rincon said that officers refused to let her speak to her son until he started having a panic attack on Sunday.

“They allowed him to call me for five minutes because my son was having a crisis. He was crying so much. His eyes were all black. He heard somebody saying they wanted to accuse him of terroristic threat,” Rincon said.

Despite multiple requests, Rincon said she has received no further information from the school about the basis of the charges against her son.

Texas law does allow children as young as 10 to be arrested and charged criminally. But Texas Appleseed and other advocates have pushed the Texas legislators in recent years to embed more legal protections for students and parents to prevent arbitrary and excessive law enforcement actions, protections Rege said the school administrators, the district police, and the school district violated in Timothy’s case.

Under Senate Bill 11, passed in the 86th legislative session, all schools must involve diverse experts—including teachers, counselors, and administrators—to conduct a fact-based, systematic investigation to determine if there is an “imminent danger and safety concern” that requires law enforcement to intervene when there is a reported threat. Schools have to consider whether the reported threat is consistent with a student’s past behavior, past written or verbal communication, and whether the student has the means to carry out such a threat, among other factors. In Timothy’s case, the reported threat was not consistent with any past patterns. Rincon says her son had never received a behavioral conduct referral before this incident.

Further, HB 473, passed in the 88th legislative session, requires that school administrators notify and provide an opportunity for parents to participate and submit information in a school’s threat assessment proceedings. Thereafter, the threat assessment team must provide their findings to the parents. Rincon says none of this occurred. If the school did actually follow the threat assessment procedure, the district rejected Rincon’s request to provide her a copy of any such findings in a letter shared and reviewed by the Observer.

“The legislation says clearly that there’s supposed to be parental involvement both in the initial assessment, and then afterward the parent is supposed to be told what was the result of the assessment,” said Ellen Marrus, professor and director at the Center for Children, Law, and Policy at the University of Houston.

In addition, the Texas Supreme Court last year issued a ruling prohibiting the handcuffing or shackling of children in juvenile court proceedings unless the child presents a substantial risk of physically harming himself or others, or of flight from the courtroom. SB 133, passed in the 88th legislative session, also restricts the use of restraints on elementary school students on school campuses. Yet Timothy was handcuffed both at school and then again handcuffed and shackled by his ankles in court.

“We don’t know if Timothy even made this threat. This was based on a report by a student and really nothing to back it up. We don’t know if the school did a threat assessment. We don’t know on what basis the court could have found that Timothy presented a substantial risk of physical harm or flight at the time to handcuff him,” Rege said. “It’s not clear on what basis they could have found this to be an imminent threat warranting a referral to law enforcement. Unfortunately, that’s what they did.”

When Timothy arrived at the detention center, Rincon said Timothy was placed in solitary confinement from Friday afternoon until his hearing Monday morning. State regulations prohibit the isolation of a minor for more than 24 hours, but Rincon was told the detention center was isolating him for COVID precautions.

According to Rincon, that morning, prosecutors attempted to have Timothy charged with making a terroristic threat against a public servant, a third-degree felony, which could result in probation or possible further detention. Instead, Judge Adela Kowalski-Garza ordered a safety risk evaluation and conditional release that allows him to attend school and remain at home until his hearing on November 8. Rincon and her son are asking a court-appointed attorney to seek that any charges be dropped. The attorney assigned to represent Timothy declined to comment.

“Timothy’s doing better. But he no longer feels safe to speak up when he needs something,” Rincon said.

When I ask Timothy how all of this has affected him, he says after a long moment of silence, “It put me under a lot of stress.”

After the incident, Rincon transferred Timothy to another elementary school where his former principal, the one whom Garza replaced, and counselor at Palm Grove Elementary now work. He says he can talk to them when he’s facing problems. He’s resumed his old routines and is dealing with more familiar stress these days—worrying about his grades, preparing for extracurricular contests, like the upcoming Battle of the Books contest, and studying to test into the gifted and talented program next year.