Vladmir Putin appears far stronger now than he did at any other time since Russia launched a full-scale invasion into Ukrainian territory in February 2022.

On the ground Russian troops are pushing hard into Ukrainian territory and have captured several villages in the past two weeks alone. Plenty of other indicators, too, show Russia’s growing strength and suggest a future in which a Ukrainian, and western, defeat is becoming a more realistic possibility.

On the domestic front, over the past year, Putin has faced down a mutiny by his erstwhile ally Yevgeny Prigozhin, who was subsequently killed in a plane crash. His only other major opponent, Alexei Navalny, perished in a penal colony in Russia’s far north earlier this year.

After being re-elected to yet another term as Russian president, Putin has also consolidated his alliances with Iran and North Korea, which supply Moscow with much-needed military equipment. This may not be the company of choice for a self-declared great power, but it keeps the Russian war machine well-oiled – in sharp contrast to the problems that Ukraine has faced over the past six months with western military aid.

At the same time, President Xi Jinping of China has reassured Putin of his continuing support during a high-profile state visit on May 16-17 2024. The seemingly strong bond between Moscow and Beijing, and between Xi and Putin personally, also appears to be more sustainable than the relationships that Kyiv has with western capitals. Within the EU, Slovakia and Hungary have repeatedly set out their opposition to continued western support for Ukraine.

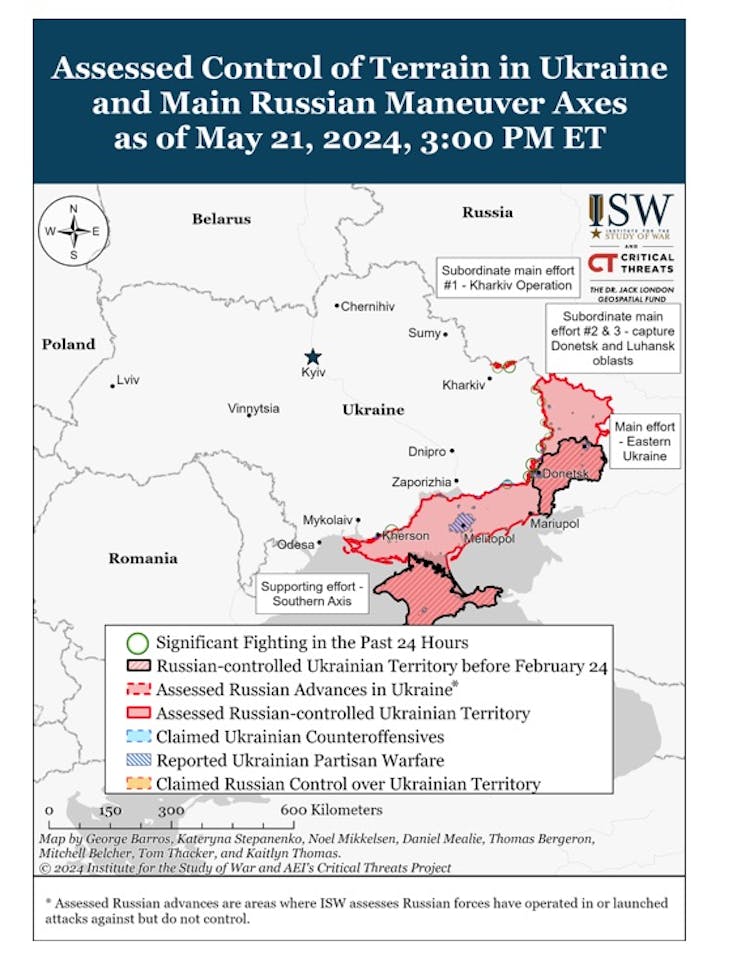

Russia’s offensive in the Kharkiv region, which began on May 10 2024, has enabled Moscow to capture several villages and drive some 10 kilometres deep into Ukraine. More than 10,000 people have been displaced amid constant Russian bombing and infantry assaults, adding pressure on already stretched humanitarian aid operations in the area and the city of Kharkiv in particular, which already hosts 200,000 displaced people.

Russian successes around Kharkiv come in the wake of territorial gains elsewhere along the 1,000km-long frontline over the past several months. While not a game changer in the Kremlin’s war of aggression against Ukraine, Moscow appears to have significant momentum behind its ground operations as Kyiv struggles to hold off Russian troops.

Russian advances this year have all but wiped out the Ukrainian gains from last year’s counter offensive. While Russia has only captured one major town — Avdiivka — since it took Bakhmut a year ago, it has captured some 500 square kilometres of Ukrainian territory over recent months.

As the Kremlin keeps up the pressure, Ukraine continues to suffer from shortages of weapons and ammunition even as more US supplies are finally beginning to reach the frontlines.

Future western support for Ukraine is far less certain than it seemed a year ago. Consequently, future-proofing aid for Ukraine is high on the agenda for Kyiv’s allies, especially with an eye to upcoming presidential and congressional elections in the US, where Trump and his supporters have suggested cutting off aid to Ukraine. President Joe Biden remains staunchly committed to Kyiv for now, but it is far from certain that he will win a second term in November this year.

Western wavering

The EU has managed to agree on a deal on how to use the profits from frozen Russian assets to support Ukraine. By contrast, G7 countries struggle to agree on how to finance ongoing support for Ukraine, especially over the use of frozen Russian assets in the west.

What appears as Russia’s strength is, in part at least, Ukraine’s and the west’s weakness. While Russia has mercilessly struck targets across Ukraine for more than two years now, Kyiv has been constrained by the types of weapons and munitions supplied by the west and by the rules of engagement attached to these deliveries, such as where they can be used. This may slowly be changing with more arms deliveries now reaching Ukraine with fewer strings attached to how Kyiv can use them.

The Kremlin has had no qualms in using convicts at the front and mobilising large numbers of young Russians for its war effort. Or in sacrificing their lives in holding off Ukraine’s counter-offensive last year and achieving its own territorial gains this year.

By contrast, Ukraine only updated its mobilisation laws in April, lowering the age of conscription from 27 to 25 years. This has yet to translate into tangible gains on the battlefield in the form of fresh, well-trained and equipped troops.

Putin makes his own decisions, almost completely unconstrained within his political regime. Buoyed by the resources that Russia can muster domestically and source from his allies, he has been able to recover from strategic and tactical mistakes.

What passes for strategy in the west is often no more than the best deal that can be agreed among 32 Nato and 27 EU members who all push and pull in different directions. The resulting permanent crisis management has, so far, prevented a defeat of Ukraine. But it has not, and will not, pave a way to victory.

Putin’s strength is relative, rather than absolute. And therein lie both a danger and an opportunity for Ukraine and the west.

More muddling through by the west will make Putin look stronger than he is and could further increase the pro-Russian narrative of an unwinnable war for Ukraine and the west. But if Kyiv’s western allies finally muster the will to provide the resources Kyiv needs, the balance of power could decisively shift to Ukraine’s advantage.

Stefan Wolff is a past recipient of grant funding from the Natural Environment Research Council of the UK, the United States Institute of Peace, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the British Academy, the NATO Science for Peace Programme, the EU Framework Programmes 6 and 7 and Horizon 2020, as well as the EU's Jean Monnet Programme. He is a Trustee and Honorary Treasurer of the Political Studies Association of the UK and a Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre in London.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.