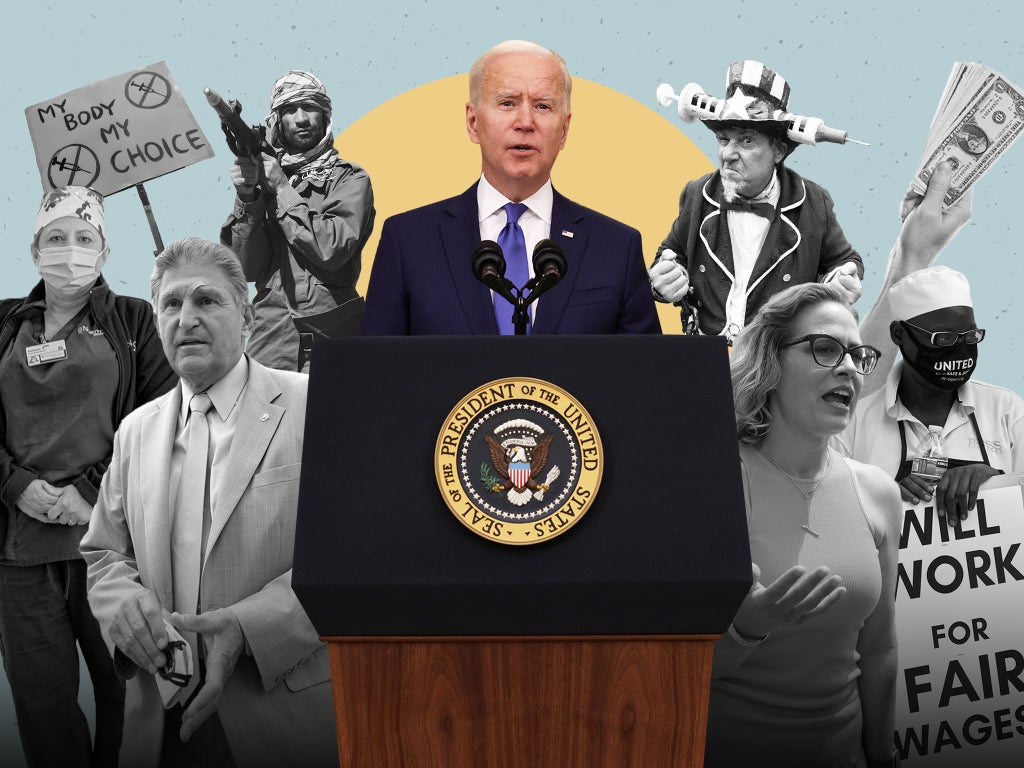

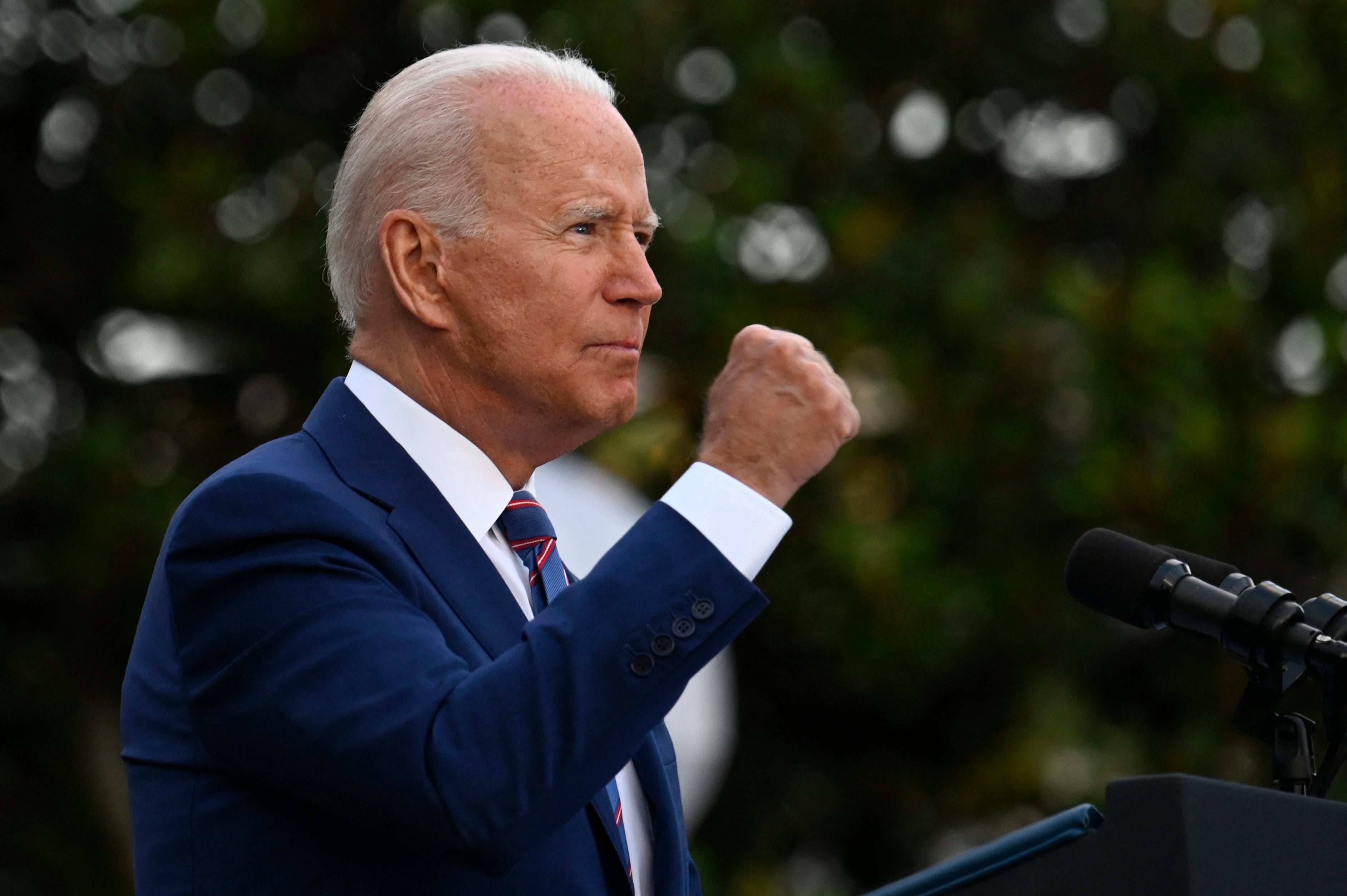

There was a moment in the summer when it seemed as if things were going to be all right. If you listened to Joe Biden as he spoke from the south lawn of the White House, if you imagined that scene bathed in Kodachrome sunshine rather the uncertain clouds that were on duty that day, you might even have felt optimistic. It was 4 July, after all – America’s national holiday.

“Today, all across this nation, we can say with confidence America is coming back together,” said the president, dressed in a navy suit, white shirt and striped tie. “Two hundred and forty-five years ago, we declared our independence from a distant king. Today, we are closer than ever to declaring our independence from a deadly virus.”

He went on: “Together, we’re beating the virus. Together, we’re breathing life into our economy. Together, we will rescue our people from division and despair.”

As he spoke, Biden’s approval rating stood at around 52 per cent, and while health officials were warning of the dangers of a new strain of the coronavirus, the Delta variant, several vaccines were available to every adult who wanted one, as well as to children above the age of 12. The average number of daily cases had fallen to below 3,000.

In the first two months of his presidency, he had signed into law the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, which provided direct payments of $1,400 to help those who had lost their livelihoods. As he stood there and spoke, he assumed similar bills were on their way.

But just a few months later, things are not looking too rosy for either the country or the president. The persistence and contagiousness of the Delta variant, and a new strain, Omicron, have upended Biden’s plan to beat back Covid, as his government has struggled to find a way to compel people to get vaccinated. This week, it was announced that the death toll in the US had passed 824,000.

While unemployment stands at 4.2 per cent, much lower than the 13 per cent seen at the height of the pandemic, consumer confidence stands at just 55 per cent, just a couple of points higher than it did last year. And data collected by the Ipsos-Forbes Advisor tracker suggests that as many as 66 per cent “anticipate that inflation will continue to rise”.

Further, after having campaigned as a candidate who promised a return to a steady hand on the tiller when it came to international affairs, Biden sat and stubbornly watched a troop withdrawal from Afghanistan turn into a deadly debacle. International allies were horrified.

‘Somehow Americans thought Biden would be able to sunset the virus’

At some point, Biden’s approval rating started to plummet. It now stands at just 43 per cent, according to the news site FiveThirtyEight, with a disapproval rating of 50 per cent.

It is almost a historic low for a president at this point in their term; the only person to score lower was Donald Trump, whose approval hovered in the mid-30s for much of his presidency.

Biden’s unpopularity has reached the extent at which many believe his party has little chance of holding on to either chamber of Congress in next year’s midterm elections. With hindsight, those words uttered in July look foolhardy.

Experts say there were several factors during Biden’s first year in office that came together to make life much tougher for him and his party. At the centre has been a pandemic that will not go away.

“Covid is the culprit. Somehow Americans thought Biden would be able to sunset the virus,” says Larry Sabato, professor of politics at the University of Virginia.

“He’s certainly taken important steps to corralling it, but no force on earth can end this scourge right now. And the nearly 40 per cent of Americans – mostly Republicans – who steadfastly refuse to take a vaccine are mainly responsible.”

“So instead of normality, which Americans voted for in electing Biden, we face months or even years more of pandemic restrictions,” he adds.

Sabato suggests that with 10 months remaining until the midterms, conditions might change for the better.

But he says: “Even though Republicans have really done nothing to deserve recapture of Congress, and they continue to support ex-president Trump’s dangerous lie that he was cheated out of a second term, Biden’s ratings – and the Democratic Congress’s performance – have made the GOP [Grand Old Party, or Republican Party] the favourite to retake both houses.”

‘I was horrified. It was like when the Taliban first came to power’

Organisations that track the president’s approval figures day by day point to a moment somewhere around May when Biden’s rating began to dip, after the first early months of optimism usually afforded to a new commander-in-chief.

Yet it was in the latter part of August 2021 when the two differently coloured lines – one orange, one green – marking Biden’s approval and disapproval scores actually intersected, and the fraction of Americans who felt good about the president’s handling of events became smaller that of those who did not.

The moment came after Biden had gone ahead with a plan to withdraw all US troops from Afghanistan, a policy he had actively campaigned on, and which the overwhelming majority of Americans supported.

Some of his advisers, particularly senior officers in the military, had argued to keep a small number of US troops in the country, perhaps just a few thousand, to continue overseeing the training of Afghan forces. Biden believed he was duty-bound to stick to a peace deal signed with the Taliban by his predecessor’s administration in February 2020.

As it happens, this was one of the subjects on which Biden and Donald Trump concurred, and he wanted to have a complete withdrawal by 11 September 2021, the 20th anniversary of the al-Qaeda attacks that had led to the invasion of Afghanistan by the US and its allies.

“I will not send another generation of Americans to war in Afghanistan with no reasonable expectation of achieving a different outcome,” he had argued in July.

However, it rapidly became clear that without those US forces, and without the sense that Washington was committed to the future wellbeing of that nation, all the years of training, along with the $80bn said to have been spent to equip Afghanistan’s armed forces, would count for little.

As summer wore on, city after city fell to the Taliban with barely a fight. On 16 August, its fighters took control of Kabul, and thousands of Afghans rushed to the airport to try to find their way on to one of the planes dispatched by the US and other nations to evacuate their citizens and those Afghans who had visas to leave the country.

In scenes witnessed in horror around the world, several Afghans fell to their deaths after chasing a vast Boeing C-17 and trying to cling to the aircraft’s landing gear.

More than 100,000 people would eventually be flown out in little over two weeks, the final evacuation leaving shortly after midnight on 30 August. Biden spoke to the nation, defending his decision, even if he said events had “unfolded more quickly” than the intelligence community had expected.

The president was widely condemned for an apparent lack of planning or preparedness. Trump, naturally, was among those who sought to use the episode to attack Biden, calling the botched episode a “humiliation”. Former British prime minister Tony Blair said the Afghan people had been subjected to a “tragic, dangerous, and unnecessary” abandonment. Anonymous US intelligence officials told newspapers that Biden had been warned about the likely rapid fall of Kabul once US troops left.

Nura Sediqe, a lecturer at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, has family members in Kabul and Herat, part of Afghan society that benefited from the stability created by two decades of foreign troop presence. A generation of young women had been able to go to school.

She recalls being deeply worried as she watched the Taliban retake Kabul.

“I was shocked, I was horrified,” she says. “I come from families that were from the urban areas that had seen stability, [where] women were going back to school. And I have cousins who are physicians and working for NGOs. There had been a renaissance of young musicians and artists, and an intellectual community emerging.

“And then to see that happen. It was like we’re just literally going back. It was almost like re-experiencing the initial shock of the Taliban coming into power in the 1990s all over again.”

‘People’s memories don't go back to Jimmy Carter and Jerry Ford’

Neil Newhouse is a Republican pollster who advised the campaigns of both John McCain and Mitt Romney in their failed bids to beat Barack Obama.

He says no single factor is behind Biden’s poor approval figures, but rather it is the “cumulative effect” of several crises he has endured. He says that three things are really harming the president – the level of perceived competence, or incompetence; the failure to really get on top of the pandemic, and the economic and political ramifications that go with that; and now inflation.

“The cost of living is now the No 1 economic issue Americans are concerned about in the country. They’re paying more, and this is really important, because it’s the first time anybody under the age of 45 has ever experienced significant inflation,” he says.

“People’s memories don’t go back to Jimmy Carter and Jerry Ford, and the first part of the Reagan administration, when we were dealing with rampant levels of inflation. Yet now we are facing it again. And so the wallets and pocketbooks aren’t going as far as they used to.”

Does Newhouse, co-founder of Virginia-based Public Opinion Strategies, believe Biden is suffering particularly because he campaigned as the “can do” candidate? He says he believes any president would pay a price, but that there is a “contradiction, between how he campaigned and how he has now governed, that is concerning to people”.

He adds: “In nautical terms, he’s lost control of the country’s rudder.”

Matthew Schmidt is an expert on politics and national security. He says that in many ways Biden has been a victim of things outside his control, so much so that the president might assume the “universe has conspired against him”.

He suggests that the continuation of the pandemic, which he says is partly a national security issue, has directly affected many if not all of Biden’s efforts in regard to his domestic agenda.

He says he believes that inflation, which may be driving Biden’s bad numbers now more than anything else, is also driven by the pandemic, adding that Democratic officials he has spoken to in Washington DC are very pessimistic about holding onto the Senate or the house in the 2022 midterms.

In regard to Afghanistan, he says the administration failed to communicate well with the American people, but that while the president had policy options, “they were impossible choices”.

Schmidt, an associate professor at the University of New Haven, rejects the criticism from the GOP over what happened in south Asia.

“I think that the Republican critique that we failed in Afghanistan, or that Biden failed in Afghanistan... it conveniently forgets history,” he says.

“The biggest at-fault president for Afghanistan is George W Bush, and his decision to invade Iraq – a country that had nothing to do with 9/11, but which pulled momentum away from Afghanistan. But you know, Biden owns it.”

‘The main improvement has been alleviating the constant spectre of government-sanctioned violence’

Biden had also vowed to take action on issues such as gun control, the climate crisis and immigration, and to seek to promote racial justice.

Yet on many issues, from protections for voting rights to an endeavour to move the nation, he has been hampered by factions within his own party – in particular, the refusal of two key senators, Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, to vote in support of several bills the president considers critical.

Just in the last few days, Manchin has announced again that he will not support Biden’s signature $2.2 trillion social safety net and climate bill, part of his Build Back Better legislation. (In November, Biden signed a $1 trillion infrastructure bill into law, thereby funnelling billions to states to upgrade aged roads, bridges, and public transport.)

In some areas, activists give Biden credit for at least trying to improve the situation. Sheerine Alemzadeh is co-founder of a grassroots Chicago-based group, Healing to Action, that works to stop gender-based violence, defend the rights of the LGBT+ community, and support people with disabilities.

Asked to point to how things have improved under Biden, she says: “The main improvement has been alleviating (not eliminating) the constant spectre of government-sanctioned violence in [people’s] daily lives. Whether it was undocumented communities, Asian Americans, women, Muslims, BLM activists, or other groups that were being targeted for violence, there is some relief in knowing that the president is not actively fuelling this violence.”

Where has he failed to deliver?

“The national responses to the pandemic are disproportionately privileging whiter, wealthier men,” says Alemzadeh.

“For example, the Build Back Better bill has so far failed to successfully win key protections for caregivers – predominantly women – and paid care workers, [who are] predominantly women of colour. Instead, the focus has been on infrastructure, a historically male-dominated industry.”

‘Biden needs to show firm leadership – people are clamouring for it’

Is there anything Biden can do to help the challenges facing America, and try to put his party in a better situation for next year’s midterms?

Juliette Kayyem, who served as Barack Obama’s assistant secretary for intergovernmental affairs in the Department of Homeland Security, argues that many of the issues the president is struggling with were inherited from his predecessor.

Yet she says she warned a year ago that Biden’s top three priorities upon entering the White House needed to be “Covid, Covid, Covid”.

In every metric in regard to the response to the pandemic, such as vaccine distribution and getting the science right, she says “Biden has done well”. She suggests that this is failing to translate into a bump in public approval because the public is still looking for an end to the pandemic.

“If I could recommend anything to the Biden administration, it would be to help the American public begin to process that we’re moving forward, but it’s not linear,” she says. “That’s the challenge he’s having.”

Kayemm, a lecturer in international security at the John F Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, also says Biden could probably do better with fewer presentations from the scientists and more speeches from himself, to show leadership and explain the challenges still being faced.

She also thinks Biden needs to show greater energy in regard to threats to US democracy, particularly in relation to the 6 January riot, though she understands why Biden has left it to the Department of Justice to take the lead on prosecuting those involved in the storming of the US Capitol.

At the same time, she says, there is great unease among Democrats over this issue. In the last couple of months, it has become clear that “this was not just a riot gone wrong”.

“[Biden] is the caretaker of our democracy, and I would like to see him really embrace that role. That is what a president does.”

Kayyem thinks the president ought to be ordering vaccine mandates, and speaking out about what happened when hundreds of supporters of Trump stormed into Congress, seeking to stop the certification of his win.

“[We need him] on more of a wartime setting, both over democracy and for Covid,” she says.

“That may not be consistent with his personality, but it’s definitely what people might be clamouring for now.”