International students make billions of pounds for the UK economy and help open up a window on the world to domestic students. That’s apparently why universities are supposed to recruit them, according to government policy.

Yet international students are at risk because of the government’s ‘hostile environment’ to migration and because of the way the sector recruits them.

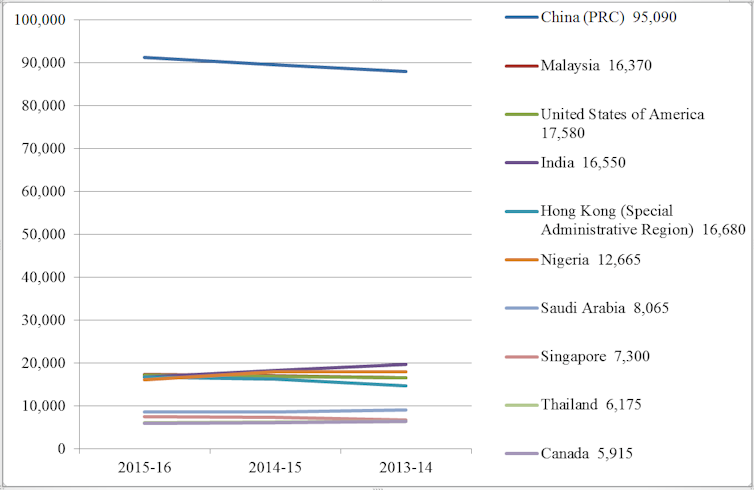

International student recruitment is entirely driven by demand and so relies heavily on students from a small number of countries (see graphic). It concentrates students in particular subjects and universities and focuses on income generation rather than education.

This is a risky proposition for a sector that relies on reputation, as future students could see this country as using them as cash-cows instead of valued partners. An alternative vision of ethical student recruitment would not only be morally sound, it would be economically and educationally sustainable too.

More is not always better

Success is often defined as growth. Policy on international students has in the past often set goals for increased numbers of students. For many institutions increasing numbers is a key indicator of success.

This growth can only be sustained if the supply of students keeps expanding. But population growth in the UK’s single most important market, China, is slowing down.

True, economic growth in key countries (such as China and India) which send students to the UK suggests growing middle classes. Middle class students tend to seek international education to gain an advantage in tough job markets. And – more importantly – they can afford it.

But as the middle classes expand, so too does the domestic provision of higher education in such “sending” countries.

Historically, the UK has been seen as “the” destination for quality higher education. But as education quality in the “sending” countries improves, the UK will gradually lose this advantage. So the UK cannot define its success in recruiting international students exclusively based on growth.

New competitors

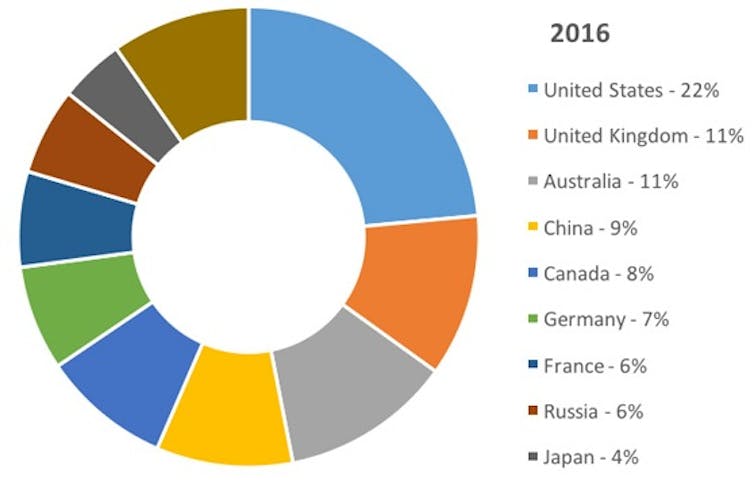

Competitive success means outdoing other providers and growing the market share. For the last decade, the UK has held second place to the US, recruiting 11% of globally mobile students (see below graphic).

But rival countries are constantly changing their strategies and policies on recruitment and new competitors are entering the market. Japan, South Korea, India, China and Malaysia now all attract significant numbers of students. Seeking to gain market share against competitors then becomes a perpetual arms race.

No perfect number

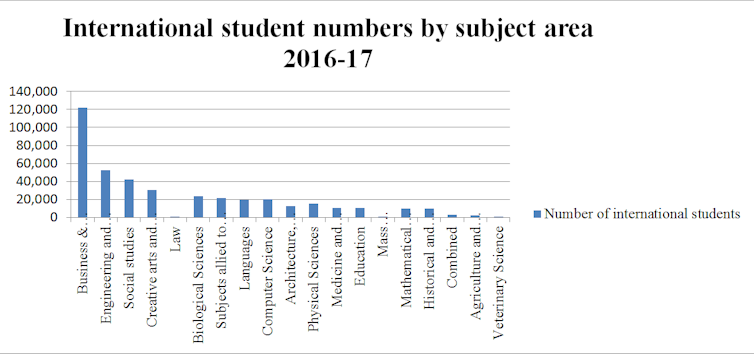

There is no perfect number or ratio of international to home students. For a start, international students are concentrated in particular subjects, like business studies (see below graphic).

International students are also concentrated in particular universities, from as few as 15 non-EU students at universities such as Leeds Trinity to over 11,000 at institutions like University College London.

Some have suggested that “too many international students” affects the “quality” of the university experience. This implies that all international students are less academically able than home students, ignoring their achievements and capacity to study in second and third languages. A more positive but equally simplistic assumption is that because there are international students in a classroom, beneficial “intercultural” exchanges will happen.

This flawed simplicity of the imagined impact of international students was made clear in a survey by the UK Home Office which asked British home students whether international students had a positive or negative impact on their “university experience”. The survey had to be withdrawn after criticism that it was flawed and “open to abuse”.

By positioning international students at odds with home students, the survey deepens a sense of exclusion within UK universities, rather than inclusion. Initiatives like this create the impression that universities are xenophobic and hostile places for international students. They should be egalitarian, diverse and hospitable environments for learning.

What would success look like?

Universities need to decide for themselves what successful international student recruitment looks like. For some, this will mean large populations in particular courses. Other institutions may be more strategic in considering numbers and distribution, linked to curricular aims, graduate outcomes and teaching approaches. Raw numbers are not a helpful indicator for this decision.

The government’s role should be to support universities by establishing a welcoming environment for international students. Committing to secure funding for higher education, rather than proposing frequent changes would offer the sector the stability to engage in long term financial planning, including – but not exclusively reliant on – international recruitment.

The sector and the government need to commit to developing international student recruitment ethically. Currently, international students achieve fewer good degrees than home students do, yet pay significantly higher fees.

International students can come to study in the UK in the full expectation of experiencing a “British” education, only to find themselves on a course with an entirely international cohort, potentially of students from the same country.

They can also start the application process, expecting to be welcomed as a guest, and find instead a confusing, expensive visa process and a hostile media and political environment.

A commitment to ethical international student recruitment would start from the premise that international education should equally benefit all students. It would mean universities putting international recruitment in service to education. And it would mean the government leading the way on valuing international students as part of a sustainable internationalised higher education sector.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.