“My body, my choice” is the rallying cry for bodily autonomy. But it’s an apt phrase for another option too, one that hasn’t been of strident public debate. If your body gets a period, there’s a healthy option for not getting one.

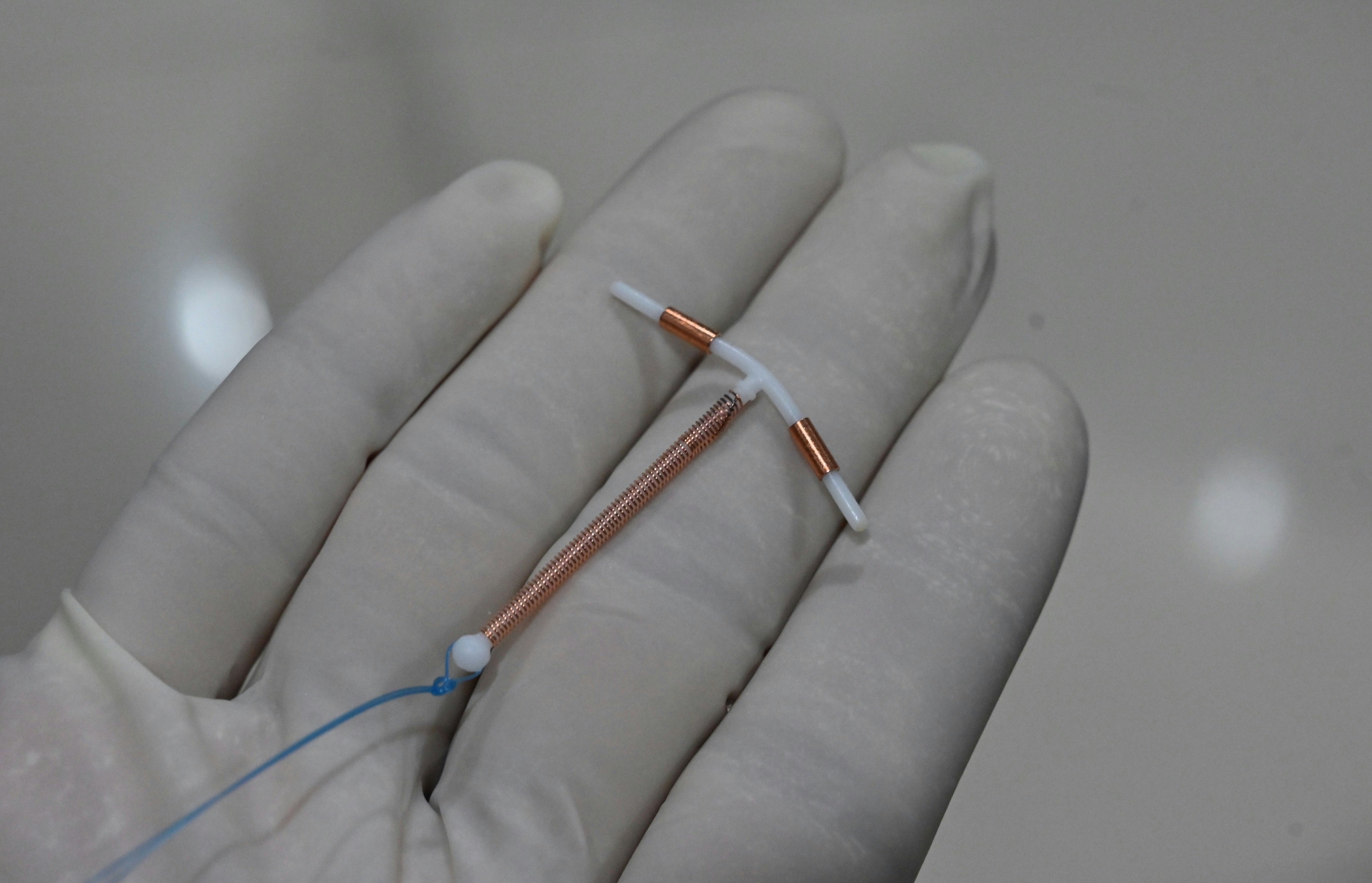

“If I had the option to be like, ‘Hey, you can just turn off your fertility cycle for as long as you want,’ I would have definitely done it way sooner, almost immediately, as soon as I turned 18,” Andrea*, a writer and producer in New York City, tells Inverse. At 35, Andrea now uses an intrauterine device (IUD) that has reduced her periods to regular spotting. (*For privacy, some sources have opted to only go by their first name.)

Abigail Williams-Joseph journeyed to her answer. “I did a 180,” the 31-year-old grad student tells Inverse. “I feel like not having a period is the best thing ever. Why make yourself suffer?”

Experts agree. “It’s absolutely not harmful to not have periods” due to hormonal birth control, endocrinologist Andrea Dunaif at Mount Sinai Hospital tells Inverse.

“The future of hormonal contraception is: Eliminate bleeding if you can.”

Before the first hormonal birth control came out nearly 80 years ago, if you were a person who menstruated, you were stuck with around 12 periods for each of your reproductive years. Now, as hormonal (and non-hormonal) birth control methods have advanced, halting menstruation is easier than ever. In fact, studies show there’s no medical reason for hormonal birth control users to menstruate.

A sense of regularity? Sure. Reassurance that one isn’t pregnant? Definitely. But those boil down to individual comfort. A growing body of research suggests that not getting a period is not only safe but could come with a slew of health benefits, suggesting that continuous birth control could be the wave of the future.

“The future of hormonal contraception is: Eliminate bleeding if you can,” obstetrician and gynecologist Richard Legro at Penn State University tells Inverse.

Why menstruate at all?

As a reproductive health refresher, the menstrual cycle goes round and round in three phases: follicular, ovulation, and luteal. These cycles run on four main hormones produced by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain: the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), the luteinizing hormone, estrogen, and progesterone.

The follicular phase starts on the first day of a period. The brain releases FSH and luteinizing hormone, both of which travel through the blood to the ovaries. These hormones then prompt 15 to 20 immature eggs to grow; the dominant egg will mature and move to the next phase, while the rest expire. In turn, these hormones boost estrogen production.

Ovulation occurs when an egg matures on the follicle. This gives way to the luteal phase when the egg travels through the fallopian tubes to the uterus. In preparation for a possible fertilized egg and pregnancy, the uterus develops a thick mucous membrane called the endometrium, which would nourish a potential little blastocyst. If an unfertilized egg reaches the uterus, then the mucous membrane sheds along with the endometrium in a period. The luteal phase ends on the first day of your period, starting again with the follicular phase.

Periods are different for everyone. They can deplete iron levels and sometimes cause such severe anemia that it lands people in the hospital. For those with polycystic ovary syndrome, in which ovaries are prone to grow cysts (which are extremely painful if they rupture), periods can be wildly unpredictable, skipping months at a time. For those with endometriosis, where the endometrium grows outside the uterus, period symptoms and cramps can be debilitating. Even for those without chronic conditions, periods can knock them off their feet.

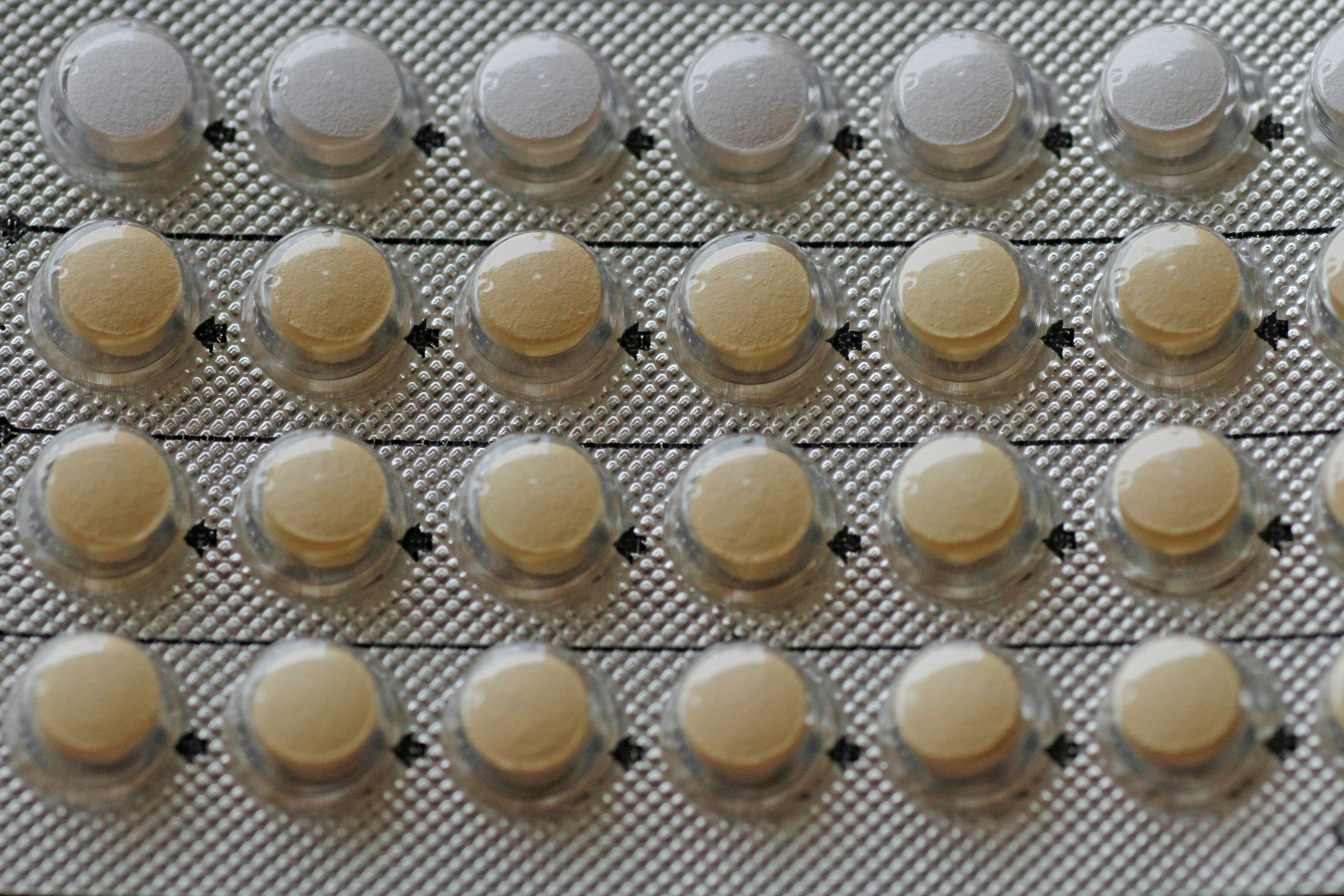

Hormonal birth control pauses this process in a few different ways. There’s the pill – some are combination pills because they administer estrogen and progesterone, while others are progesterone. A risk of progesterone-only pills may be bone density loss because estrogen boosts bone density. Some argue that this loss leads to a higher fracture risk later in life, but there isn’t enough evidence to support that.

Hormonal IUDs don’t affect reproductive glands. Users still have their regular cycle, but eggs cannot fertilize and attach to the uterine wall. They also thicken cervical mucus so that sperm can’t travel through. Some prefer this method because their hormonal cycle continues, but is still highly effective at preventing pregnancy.

Injections like depo medroxyprogesterone acetate, a.k.a. Depo-Provera, stop follicle development, so cycling and uterine buildup halt. If there’s no mature egg, then there’s no endometrium creation and no period.

A history of misconception

First-wave feminist Margaret Sanger holds the title of the mother of birth control. She opened the U.S.’s first birth control clinic in 1916. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, she followed contraceptive scientific research and contributed money to the efforts. In 1960, the FDA greenlit the sale of oral contraceptives. Five years later, 25 percent of married women under 45 had it, signaling a new era for bodily autonomy.

Even back then, researchers knew that the pill didn’t need to include a monthly bleed. The Catholic Church gets some of the blame for those placebo pills. Catholic obstetrician and gynecologist John Rock aided biologist Gregory Pincus with clinical trials for the pill. Rock believed everyone had a right to contraceptives but knew that the Catholic Church would deem the pill unnatural and deter prescription. Indeed, in 1968 Pope Paul VI denounced birth control. In 1970, Rock campaigned for the Vatican’s approval. These pills were no more unnatural than the Catholic-approved rhythm method, he argued, because they still mimic a monthly cycle.

“It was felt that this might fly easier with the Catholic population if indeed there was a period,” gynecologist Malcolm Munro at the University of California, Los Angeles hospital tells Inverse. “So this was a social decision…to perhaps make it more palatable for the Catholic Church.”

He says that into the 70s, when other hormonal birth control came on the research scene, researchers already knew that continuous hormone administration was safe. “This whole notion of continuous is in no way new,” he says.

The benefits of continuous birth control

It’s tricky to pinpoint what makes suspended menstruation icky. “Unnatural” is a commonly floated word. A clear part of the ick factor is a sense that something — menstruation is the monthly shedding of the uterine lining that builds up in case a fertilized ova needs to float in it — isn’t getting flushed out.

“Patients say to me, ‘Oh my god, I’m not flushing out my system, there must be buildup,’” Mount Sinai’s Dunaif says. “But no, there’s no buildup. It’s an atrophic uterine lining.” Endometrial atrophy occurs during menopause when the body stops producing as much estrogen. The difference is that when a pill is doing the work, it’s fully reversible.

So when should doctors begin to offer zero period as a legitimate option, not just as a side effect?

“We need to do much better education, to say you have a choice.”

It’s undeniable that more people are starting contraceptives for a purpose other than pregnancy prevention. In a 2018 survey of over 72.5 million people between the ages of 15 and 49 who menstruate, 65 percent used contraceptives. Twenty-one percent of these contraceptive users took the pill, and 16 percent relied on long-acting reversible contraceptives, such as the hormonal IUD or implants.

Increasingly, users choose contraceptives for reasons unrelated to birth control, such as cycle regulation, symptom management, and skin clearing. For some, it makes sense to halt menstruation: Those with a gynecological disorder that results in painful periods and those with clotting disorders or excessive bleeding could benefit from contraceptives.

“We need to do much better education, to say you have a choice,” Dunaif says.

Martha, a 27-year-old library science graduate student in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, has endometriosis, a condition that affects an estimated 11 percent of Americans with uteruses between 15 and 44 — more than 6.5 million people. Their IUD treats the debilitating pain and halts their period entirely. “It does freak my mom out,” Martha tells Inverse. “[She] thinks that not having the period must not be good for me because I’m not going through the regular cycle in my body.”

And that’s before considering the money, the waste, the fretting, and the time that goes into tending to a period. A 2017 paper in the Rhode Island Medical Journal found that, on average, one spends $20 per period. From an environmental perspective, pads and tampons long outlive their one-time use. Pads take 500 to 800 years to decompose, though their plastic never biodegrades. That, plus plastic tampon applicators and sleeves holding new pads and tampons, generates about 400 pounds of menstrual waste in one person’s lifetime.

Period-specific underwear and reusable silicone cups can ease some of these issues. There are ibuprofen and home remedies, though not everyone can safely use painkillers. None of that fully compensates for the fact that you still have your period. For those who see their period as a problem, eliminating it may be better than compromising.

But nobody needs to justify why they do or don’t want a period, or want to use hormonal birth control at all. “The psychic well-being that may give somebody – that’s enough of a reason to do it,” Legro from Penn State tells Inverse.

What is the future of periods?

That said, getting a period is not necessarily bad, and a period isn’t excruciating for everyone. Some enjoy the regularity, and even if the body isn’t flushing out toxins the way Dunaif’s patients are concerned, a feeling of shedding something internal can bring personal comfort. Assurance that you’re not pregnant is another big one.

Some even exalt their period. They revel in the process that comes with their body, delving deep into how their hormonal cycles affect every aspect of their mood, syncing up with other friends, or the lunar cycle.

Erica, a copywriter in St. Paul, was happy to start menstruating regularly after years of unpredictability. After the 25-year-old started the pill in 2022 after being diagnosed with PCOS, she got a regular period for the first time in her life. “I have periods again, and they're pretty chill,” she tells Inverse.

It’s also important to note that medically induced amenorrhea — the medical term for not getting your period from birth control — is different from one’s period just stopping one day. Professional runner Tristin is familiar with this concept. “As an athlete, getting a period has always been a signal to me that I’m hormonally healthy, that I’m giving myself enough nutrients,” Tristin, a 28-year-old living in Boone, North Carolina, tells Inverse.

Typically when one’s period stops without medical intervention, it means something’s off. It could be a side effect of an eating disorder or an outcome of an athlete pushing themselves too much. This could partly be why so many shudder at the thought of halting periods.

Tristin started using hormonal birth control at 16. In 2019 she started using the low-hormone Kyleena IUD, which gave her a “super light” period, and in June 2022 switched to the Mirena IUD, which suspended her period entirely. Even for an elite athlete, no period from an IUD is a different story than no period, period.

Before using an IUD, Tristin had “pretty painful” periods. “I felt like it was affecting my athletic performance,” she says. “If I had my period during a competition, I had worse digestive issues and just cramping and felt like my stomach was just not cooperating.”

What is the future of birth control?

As more methods of hormonal birth control come about, and more people gain access to them, more people have suspended their periods. In 2015, writer Alana Massey published an essay in The Atlantic about deliberately halting her period.

In the works are a new injection and a new vaginal ring. Diana Blithe, chief of contraceptive programming at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, describes that the primary goals for these contraceptives in development are to further reduce the profile of side effects. In other words, make it even safer and more pleasant not to get a period, if that is the choice you want to make. With the injection as a long-acting reversible contraceptive and the ring as a wearable device, these developments do away with the risk of increased pregnancy from unintentionally skipping pills.

The injection, Blithe says, is in active clinical trials, though still in early stages. What distinguishes it is it doesn’t interfere with the glucocorticoid pathway, which regulates gene transcription, metabolism, and immune response in nearly every cell. Blithe also says that so far, participants aren’t showing weight gain as a side effect. Both glucocorticoid interference and weight gain are associated with Depo-Provera. She says that trial participants have been Depo users in the past, and they like this new injectable much better. Like Depo, it could be managed as self-administered injections every three months.

The current ring on the market, NuvaRing, contains a synthetic estrogen called ethanol estradiol, which is associated with a higher incidence of blood clots. The ring in development administers natural estrogen, which Blithe says would be a much safer option for those at risk of venous thromboembolism, meaning they’re prone to blood clots in veins.

The future of hormonal birth control defies the notion that everyone who menstruates must suffer through one bloody week each month and that the only consolation is a common bond.

The future of hormonal birth control defies the notion that everyone who menstruates must suffer through one bloody week each month and that the only consolation is a common bond. They can commiserate and scold non-menstruators – usually cis men – who cruelly underestimate the pain.

But even better than a consolation prize is not having a period if you don’t want one. Why be forced to look for a silver lining when you can dissipate the cloud altogether if you wish? There’s nothing inherently bad about having a period, but it’s foolish to coerce everyone to have one when there’s another option available. For some, menstruation needs no consolation prize because it’s meaningful in itself, whether that’s simply reassurance that one isn’t pregnant or a sense of reverence for this function.

Safe medical amenorrhea as an option isn’t a call to cancel periods wholesale, nor does it demonize the process. Menstruation can be sacred, but that’s in the eye of the menstruator. The future of hormonal birth control simply allows those who don’t want a period to live as they wish. Their body, their choice.

THE FUTURE OF YOU explores the tantalizing advancements in personal health, from a future without periods to computers in our brains. Read the rest of the stories here.