If you thought energy bills in Britain were capped at £2,500, you are not alone. Even Prime Minister Liz Truss recently made the same mistake, incorrectly claiming that no household would pay more.

What Britain has actually done, in common with many other countries facing an energy crisis this winter, is cap the price of units of energy – the amount you pay per watt of electricity or gas. An energy bills support scheme now caps electricity and gas prices at 34p per kilowatt-hour (kWh) and 10.3p/kWh respectively.

However, the way this has been communicated has led to widespread confusion. Importantly, there is no cap on overall bills – if you use lots of energy, you will still have a large bill, albeit less than without a cap.

Yet rather than express the interventions as a cap on unit costs, there has been a tendency to refer to the average cost of energy, per household, per year. For instance, for an average household in the UK, the latest cap equates to around £2,500 for a whole year. That meant the price cap is often reported as £2,500 per year – especially in headlines and in short news clips, when space and time are short.

Such reports perhaps explain why Truss and others thought the figure is a maximum, not an average. In response, businesses, charities and government agencies have launched public communications campaigns to stress that bills will depend on usage.

People are assumed to be energy-illiterate

Besides the waste of energy and effort caused in the near term, this exemplifies a broader, problematic approach to public engagement when it comes to energy, about which the average citizen is assumed to be largely illiterate. There is an assumption held by politicians and the media, and not helped by those in the industry, that energy is a highly technical issue, and units such as kWs and kWhs are beyond the comprehension and interest of the general public.

This assumption is self-fulfilling. It also goes against the need for greater public engagement on issues of energy and climate change, and related concepts such as efficiency and sufficiency (not using any more energy than needed) that will be crucial if the transition to net-zero emissions is to be inclusive and just.

Energy doesn’t have to be complicated. Like any major commodity and essential service, there are various technical aspects relating to generating technologies, electricity transmission and so on. But as a resource that underpins everyday life, it is also a regular topic of conversation. Meaningful public engagement must be underpinned by accessible language and relatable concepts, but it doesn’t need to avoid any technical information.

During the COVID pandemic, technical concepts like R (reproduction) numbers and infection risk factors were regularly communicated to the public, which helped encourage the widespread behaviour change needed to control the pandemic. In the case of the UK government’s energy price caps, attempts to keep things simple has backfired, generating misinformation and widespread confusion.

People are already engaged

While providing information is important, what is needed are more varied modes of engagement. This should begin with the observation that people are already engaged with energy systems in the course of everyday life, have many diverse capabilities, and have a critical role to play in achieving net zero.

What you know about energy probably comes through everyday experience, rather than technical detail. For instance, people tend to categorise appliances by function, such as cooking or entertainment, rather than by energy consumption.

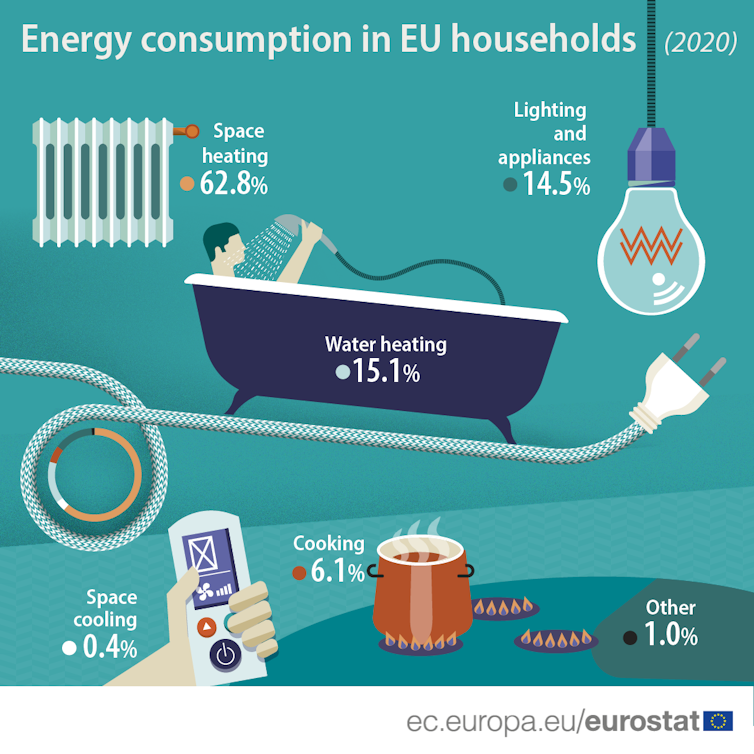

We should build on this, without dumbing down how energy is discussed in the media. Infographics such as the one below produced by Eurostat can help improve understanding about where most energy is used in the home, and help people to focus on where they might make savings (no, it’s probably not worth unplugging your phone charger).

Our research shows that most people in the UK agree that people need to change their domestic energy use to tackle climate change, while the link between energy and emissions is broadly understood. We also find strong support for phasing out gas boilers, and for many other net zero policies that would require behaviour change.

Support for these measures tends to increase when people are given accessible information and time to think about different options, for example, as part of moderated discussions between a representative sample of the population, known as citizens’ assemblies.

The report from the UK Climate Assembly emphasised the need for education, fairness and choice to underpin the path to net zero. When it comes to the price cap, people don’t want to be condescended to, but provided with the information they need to fully understand what the government is doing to help them.

Sam Hampton receives funding from the Economics and Social Research Council, the UK Energy Research Centre, and Innovate UK.

Jan Rosenow is affiliated with the Regulatory Assistance Project.

Lorraine Whitmarsh receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council and the European Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.