The United States has criticised South Africa’s decision to hold military exercises next month with Russia and China as the war in Ukraine rages on.

The exercises – called Mosi, which means “Smoke” in Tswana, one of South Africa’s 11 official languages – will see 350 of South Africa’s soldiers train alongside their Russian and Chinese counterparts.

The drills will happen off South Africa’s coast from February 17 to 27 and will take place during the first anniversary of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

“The United States has concerns about any country … exercising with Russia as Russia wages a brutal war against Ukraine,” Karine Jean-Pierre, the White House press secretary, said on Monday.

The comments from Washington came hours after Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov met with his South African counterpart, Naledi Pandor, in Pretoria.

South Africa defended its decision to hold the drills.

“All countries conduct military exercises with friends worldwide,” Pandor told reporters. “There should be no compulsion on any country that it should conduct them with any other partners.”

She said the exercises were “part of a natural course of relations between countries”, adding that Pretoria should not be denied “the right to participate” in the drills.

Lavrov said there was no need for any country to be concerned about them.

“Our exercises are transparent,” he told reporters. “We, together with our South African and Chinese partners, have provided all the relevant information. We don’t want to provoke any scandals or confrontation. We just want every country to be able to have their own rights in the international systems as provided by the UN Charter.”

South African government officials described Lavrov’s visit, which came a day before US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was due to arrive in South Africa, as an ordinary visit.

Lavrov’s trip has nevertheless been described as insensitive by some opposition parties and the small Ukrainian community in South Africa.

To understand why the trip is getting so much attention within and outside the country, it is important to examine Pretoria’s stance in the war and its relationship with Moscow.

What is South Africa’s position on the conflict?

South Africa says it is impartial in the conflict, which started after Russia sent its troops into Ukraine 11 months ago.

In March, Pretoria abstained from voting on a United Nations resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and calling for Moscow to withdraw its forces immediately.

South Africa, along with 34 other countries, also abstained from a vote at the UN condemning Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territories in October.

“South Africa believes that the only path to peace is through diplomacy, dialogue and a commitment to the principles of the United Nations Charter, including the principles that all member states shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means,” Pandor said in her remarks after the meeting Lavrov.

“It is important, therefore, to mention our sincere wish that the conflict between Russia and Ukraine will be brought to a peaceful end through diplomacy and negotiations as speedily as possible,” she said.

But South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who has offered to mediate in the conflict, has blamed NATO for the war. The alliance ought to have “heeded the warnings from amongst its own leaders and officials over the years that its eastward expansion would lead to greater, not less, instability in the region”, he said in March.

Why is South Africa neutral?

Pretoria and Moscow have long historical ties dating back to the times of white minority rule in South Africa.

South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC) has longstanding relations with Moscow forged during the liberation struggle against apartheid. Many of the ANC leaders were educated or received military training in the Soviet Union. Some, like the late Eric “Stalin” Mtshali, have Russian nicknames thanks to their connections to Moscow.

The Soviet Union backed the liberation movement with arms and money. This was in stark contrast to the West, where the United States labelled the ANC a “terrorist organisation”. Washington considered the liberation hero Nelson Mandela a “terrorist” until 2008.

South Africa is also a member of the Non-Alligned Movement. The 120-country movement, formed during the Cold War, is not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc or superpower.

Since gaining independence in 1994, a core pillar of South Africa’s foreign policy when it comes to conflict resolution has been to call for dialogue. Pretoria has backed peace talks in several conflicts in Africa and most recently hosted peace talks between Ethiopia’s government and rebels from its Tigray region.

Pandor has repeatedly insisted that South Africa will not be dragged into taking sides and has criticised the West for selective condemnation of Russia while ignoring other acts of aggression like the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory.

Are there other ties between Moscow and Pretoria?

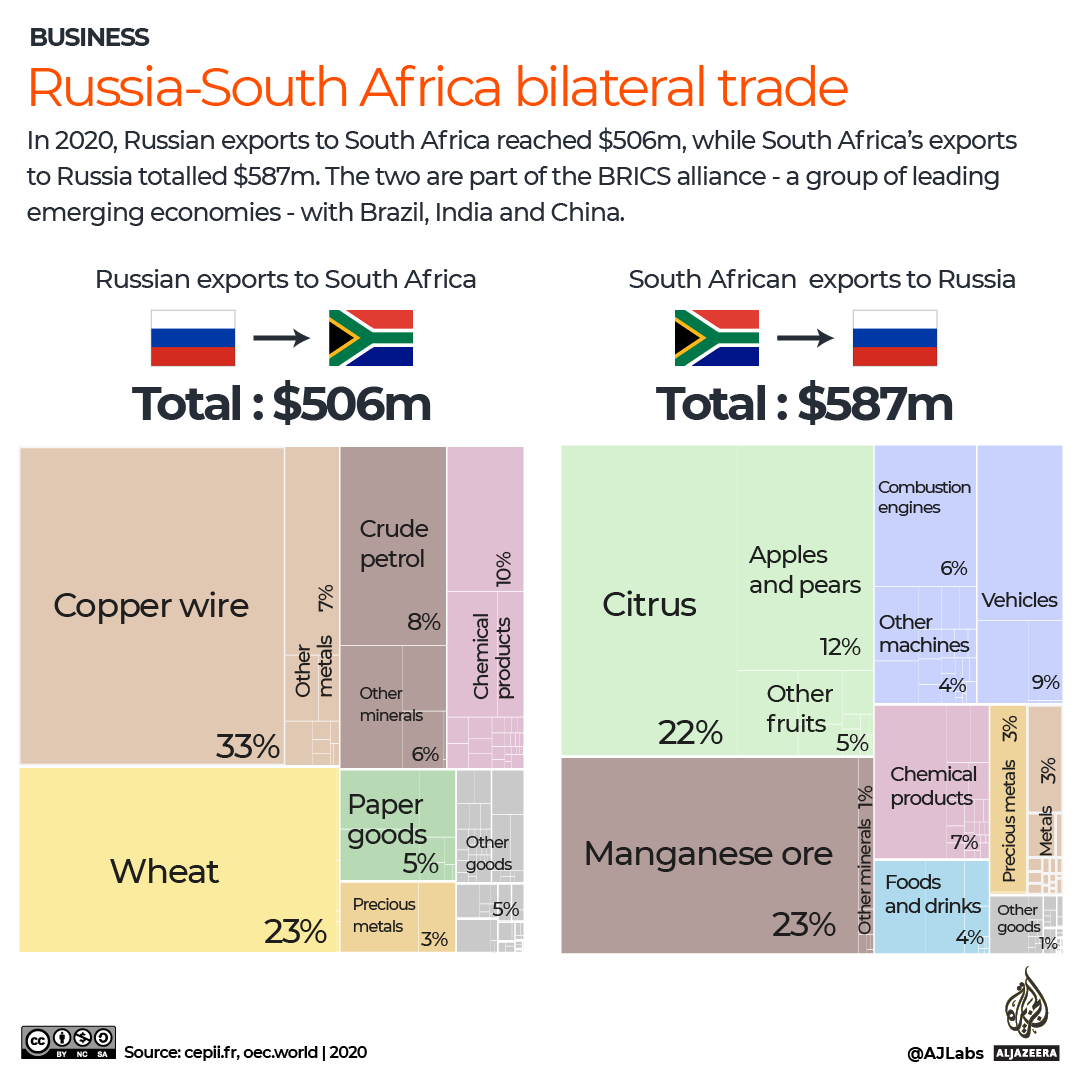

Both South Africa and Russia are members of BRICS, an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. The bloc aims to promote trade and security ties between member countries.

South Africa, the most industrialised country in Africa, has been a trade partner with Russia for years. South African exports to Russia were valued at $587m in 2020 while Russian exports to South Africa totalled $506m.

How is the government’s stance viewed in South Africa?

Last week, the foundation of the late South African Archbishop and Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu criticised the naval exercises, calling the drills “disgraceful” and “tantamount to a declaration that South Africa is joining the war against Ukraine”.

The Democratic Alliance, the country’s main opposition party, has also been vocal in its opposition to the government’s neutral stance, calling on South Africa to side with Kyiv.

“We are already involved in this war,” John Steenhuisen, the party’s leader, told parliament in March. “Our government can’t be seen to be supporting Russia’s aggression.”

“Let’s put the country before party politics and think what this war will mean to us and what will be its impact on our economy,” he said.

Steenhuisen also visited Ukraine in May for a fact-finding mission.