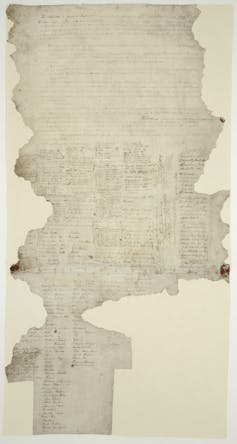

All three parties in New Zealand’s new coalition government went into the election promising to diminish various Māori-based policies or programs. But it was the ACT Party that went furthest, calling for a referendum to redefine the “principles” of te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi.

The referendum didn’t make it into the coalition agreement, but National and New Zealand First have agreed to a Treaty Principles Bill going to a select committee for further consideration.

Meanwhile, NZ First negotiated a review of all legislation referring to the Treaty principles and to “replace all such references with specific words relating to the relevance and application of the Treaty, or repeal the references”.

These proposals are significant because they would reverse a decades-long bipartisan trend towards increasing the Treaty/te Tiriti’s influence in public life.

The Treaty and its principles

Over the past 50 years, the treaty/tiriti principles have been developed by parliament, the courts and the Waitangi Tribunal. The principles include partnership, reciprocity, mutual benefit, active protection of Māori interests, and redress for past wrongs.

ACT argues that these principles give people “different political rights based on birth”, meaning Māori have a bigger say in political decisions, and that this affronts political equality.

Others have argued the principles overshadow the substance of te Tiriti, meaning Māori have less say, and that this is actually where inequality lies. This in turn explains why, for example, Māori die an average six to seven years younger than other people.

When te Tiriti was presented to Māori chiefs (rangatira) in 1840 by the Anglican missionary Henry Williams, he stressed the protection of Maori authority over their own affairs was a serious and unbreakable promise.

Most importantly for the current debate, people were given reasons to believe the government would not interfere with a Māori right to be Māori.

Specifically, the British Crown would establish a government (Article 1 of te Tiriti). Māori would enjoy tino rangatiratanga over their own affairs (Article 2) – the inherent authority to make decisions, not the government’s gift to take away as it pleased.

Māori would also enjoy the rights and privileges of British subjects (Article 3), and there would be “equality of tikanga” (cultural equality). By now, “subjecthood” has come to mean New Zealand citizenship, and the concept continues to evolve.

Political equality requires cultural equality

ACT’s alternative principles do not use the language developed to deal with te Tiriti’s/the Treaty’s meaning over the past 50 years. They state:

All citizens of New Zealand have the same political rights and duties.

All political authority comes from the people by democratic means including universal suffrage, regular and free elections with a secret ballot.

New Zealand is a multi-ethnic liberal democracy where discrimination based on ethnicity is illegal.

These could be interpreted to support the idea that cultural equality means Māori people are allowed to be Maori when they participate in public life. But ACT’s election campaign rhetoric, and the coalition government agreements, suggest the opposite intent.

The plan to abolish the Māori Health Authority is an example. It was established in 2022 to ensure Māori experts could make decisions about funding and providing Māori primary health services.

This was based on findings by both Waitangi Tribunal and parliamentary select committee inquiries that health policies were failing Māori – partly because there was no sufficient mechanism for Māori to systematically contribute to decisions about services and delivery.

Health services will remain universally available. But it’s not clear they are intended to work equally well for everybody, given the government has provided no alternative to address the policy void the Māori Health Authority was intended to fill.

In other words, there’s no space for specific Māori leadership in making decisions about what works and why, and what should be funded as Māori primary health services. Māori culture won’t count in decision making.

Diminishing that cultural perspective means democratic equality is, in effect, conditional on not bringing a Māori perspective to public life.

Policy that works equally well for Maori

Equality means every citizen should expect a policy to work for them as well is it works for anybody else. Te Tiriti may help achieve that. But without it, there may be a gap between the language of equality and the policy intent.

For example, the government plans to repeal the Treaty section of the law governing Oranga Tamariki, the state’s child care and protection agency. This section says te Tiriti requires Oranga Tamariki to recognise the cultural backgrounds of Māori children in its care.

Oranga Tamariki must also recognise it’s also the job of Māori families, iwi, hapu and other agencies to support Maori children who need care and protection.

Read more: Who are the 'kōhanga reo generation' and how could they change Māori and mainstream politics?

There’s nothing in this section to support ACT’s election campaign statement that the previous government’s Treaty policies contributed to an “unequal society [where] there are two types of New Zealanders. Tangata Whenua, who are here by right, and Tangata Tiriti who are lucky to be here”.

This section says no more than that Māori people should expect state care and protection policies to work for them. Yet it is the only section of any legislation the government is explicitly committed to repealing.

To avoid doubt, and affirm the substantive equality of all people, the government could simply replace references to the Treaty with the words: “This Act will be applied to work equally well for Māori as for all other citizens.” After all, if this is not the intent of any law, then equality per se is not its intent either.

Political authority and people

ACT’s second proposed principle states that “all political authority comes from the people”. But as I argue in my recent book Sharing the Sovereign, that means all people must be able to express that authority in ways that are personally meaningful.

People’s actual experience of the democratic system must give them reasons to believe it works as well for them as for anyone else. Those reasons cannot arise –for anyone – in a cultural void.

We all think and reason about what governments should do, and what they should leave for others, through a cultural lens. If some people may only participate in public life through a cultural lens someone else has imposed, then they are not among the people from whom “all political authority comes”.

Dominic O'Sullivan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.