Vibha Wasandi doesn’t know what to blame for her weight: the fact she may have inherited a genetic predisposition to obesity because her mother and grandmother were both obese, or whether it was because she had three caesarean sections in five years.

“All I know is that I walk around the house a lot, eat small portions of healthy food, don’t drink alcohol or have fried snacks and I’m still obese,” she said.

Wasandi, 62, has given up on diets. “I don’t think they have a lasting effect. You have to just have a healthy lifestyle every day. That’s what I try to do,” she says.

Although she has a maid and cook in her large New Delhi house, Wasandi keeps moving around, doing many chores herself, and walking the dog. Luckily for her, her only ailment is diabetes. No hypertension. No joint problems due to weight. No heart issues.

“I am lucky so far, but if I developed weight-related medical issues and had to go in for bariatric surgery, I would want it covered by my insurance,” she said.

As obesity has rocketed, from a figure of just over one million obese Indians in 1975, so has the demand for bariatric surgery. Surgeons last year performed more than 100 weight-loss operations a day, a 12-fold increase from a decade ago. Doctors say the demand is growing at 29 per cent annually.

The problem of obesity starts early in India. The country has the second highest number of obese children – 14.4 million – in the world after China. A sedentary lifestyle and junk food are the main causes. Indian diets are carbohydrate-heavy and oil-rich.

How Chinese children are at higher risk of obesity from lack of sleep and late bedtimes

What’s distinctive about India, though, is that two cultural factors help obesity take root. One is the mental connection some Indians make between being fat and being “prosperous”. In a poor country, being plump is seen as a sign that you eat well and are, therefore, well off – the reverse of the West, where the rich try to be thin as rakes.

Until some years ago, peasants in Punjab used to drink melted butter as a sure-fire way of getting fat fast and boasting of a wide girth. This sentiment is fading yet remnants of it remain, lurking vestigially in the corners of the mind of many Indians who equate being thin with being poor. Fat children also tend to be regarded as “cute”.

Second – and this factor also has to do with poverty – is the tendency of middle-class Indians to shun physical work as something the “poor” do. Thus, for millions of Indians, sitting at a desk all day in an office is the ultimate dream job (and preferably doing very little, too).

The moment a lower middle class family starts feeling financially comfortable, it hires a full-time maid or a part-time cleaning woman.

Not doing the housework is a symbol of status. There are many well-off women who sit in their drawing rooms with a bell resting on the coffee table. They ring to summon their servants, even to get a glass of water, instead of getting up to speak to them.

“All these women would be better off moving around the house more and doing some housework, but being inactive is seen as a luxury, rather than health hazard,” says gym trainer Alka Pandit.

Why heart attacks are leading cause of death in women, and why many women are unaware of the higher risks they face

Yet another cultural factor, though it may sound trivial, is the nature of the clothing most Indian men and women wear. The petticoat worn under a sari is tied with a drawstring. So is the lower garment – the salwar – worn by women, and the pyjama – worn by men.

It means that waists can expand and all the wearer has to do is loosen the drawstring an inch or two, in what columnist Santosh Desai facetiously called The Great Indian Rope Trick. Since the drawstring can be extended indefinitely, it can never get so short that the wearer has to discard the garment and buy another one.

The realisation that one is overweight can take so long to dawn that the damage is well and truly done by then.

India’s obesity problem is surpassed only by that of China and the US. For India, the difficulty is that it does not make sense for it to spend the scarce resources of an inadequate health care service dealing with the medical conditions that arise from obesity, such as hypertension, diabetes (India has 80 million diabetics), joint problems, heart disease, and respiratory issues. Moreover, the same system has to deal, ironically, with the effects of malnutrition.

Are Hongkongers really getting fatter? The recent obesity alarm explained

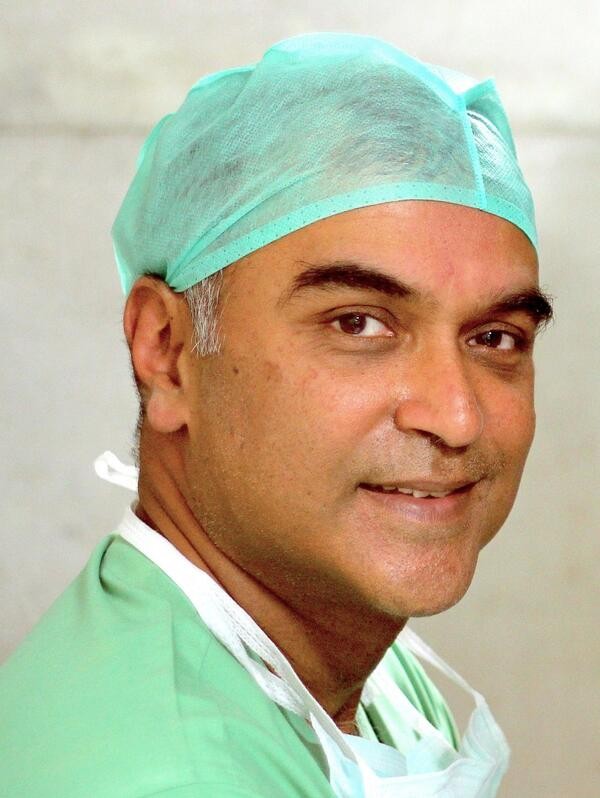

“The cost to the individual and to the nation of obesity are very high – the cost of heart disease, renal transplants, knee replacements and diabetic treatment is colossal. That’s why we want bariatric surgery covered under medical insurance. But somehow the momentum for this among the public hasn’t yet built up, despite politicians and celebrities getting bariatric surgery,” says Dr Arun Prasad, president of the Obesity Surgery Society of India.

After lobbying by the society, one insurance company has accepted bariatric surgery as eligible for insurance. A government insurance scheme covering civil servants has also accepted it. But there is a long way to go before the big national insurance companies stop treating bariatric surgery as a cosmetic procedure.

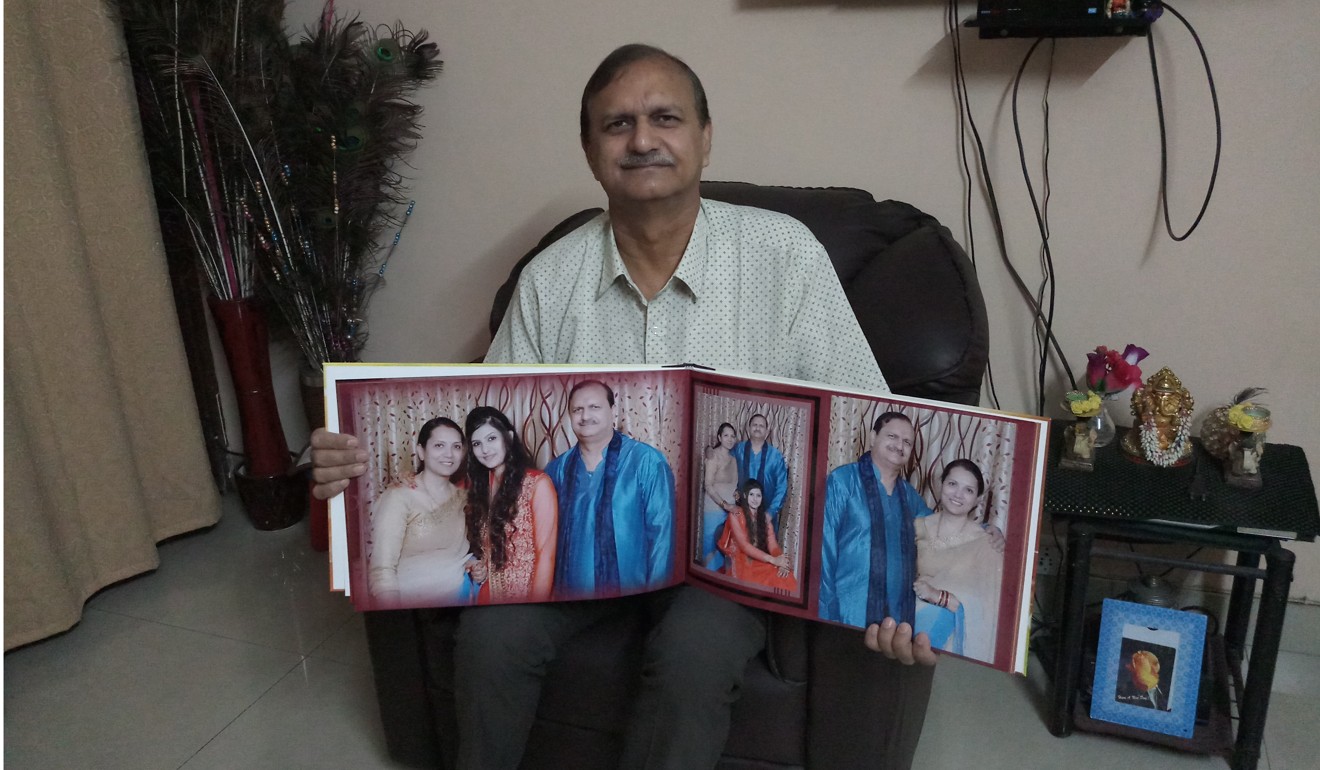

Dr Rajiv Sinha, 57, a paediatrician at Apollo Hospitals, is all too aware of the irony of this juxtaposition. Malnourished mothers often bring their malnourished children into his room. Sitting behind his desk, his bulk, when he weighed 110kg (243lbs), used to loom uncomfortably large against the skinny mothers with their stick-thin children.

Sinha’s weight gain was gradual but inexorable. He is a gregarious man who loves socialising. Endless drinks parties and dinners invariably resulted in a high intake of fatty food, quite a lot of alcohol and eating late at night.

He tried eating less. He bought a treadmill and did 3km (2 miles) a day on it. But his weight simply would not go down.

How bariatric surgery helped a star Singapore chef lose 55kg

Nine months ago, he had bariatric surgery, not so much because his weight was excessive but because he wanted to avoid the complications brought on by surplus weight. He was already diabetic and hypertensive. After surgery, he weighs 85kg and takes just one pill a day, for his diabetes.

“I feel well. My knee pain has gone. It’s good that now I can continue my social life but can’t eat as much as before because my stomach has shrunk in size,” he said.

Sinha agrees with Prasad that the cost of covering bariatric surgery under medical insurance is more than outweighed by the costs to patients of ongoing treatment for weight-related conditions. “If you are paying for diabetes and heart disease problems, the cost of daily medicines and treatment is high and just keeps getting higher,” says Sinha.

He concedes that bariatric surgery is not the ideal solution; a healthy lifestyle is the solution. But he supports Prasad in saying that the government should not stand aside while people develop a range of serious health problems caused by obesity because they cannot afford bariatric surgery.

Prasad and other obesity surgeons are waiting for the government’s response to their petition, handed to the country’s health minister at last month’s conference, demanding that obesity be classified as a disease and not a cosmetic condition.