Update: After unionized nurses at Austin’s Ascension Seton Medical Center carried out a one-day strike on June 27, Ascension Health refused to allow them to return to work until July 1. Ascension said this was a requirement of the staffing agency it used to bring in replacement nurses for those four days, but nurses—who’d hoped to return to work the day after their strike—described it as retaliation that could endanger patients.

Kris Fuentes, a registered nurse in Ascension’s neonatal intensive care unit who returned to work with her colleagues on July 1, told the Texas Observer on July 5 that myriad problems occurred while the regular nurses were locked out. In her unit, she observed that blood samples had been collected improperly, requiring additional “sticks” of newborn infants, and that babies on respiratory support had not had their oxygen levels recorded often enough. She also heard from colleagues in other units that adult patients with wounds had gone without dressing changes, that cardiac infusions had been administered improperly, and that surgeries had taken longer than expected.

“Quite honestly, it was appalling,” Fuentes said. “It’s really unfortunate that Ascension chose this route.”

In a statement to the Observer, an Ascension spokesperson said that 30 percent of nurses represented by the National Nurses United union had chosen to continue working rather than participate in the strike. “This support, along with the temporary staff we engaged, ensured we were able to continue to provide quality patient care across all disciplines,” the spokesperson said, adding that Ascension remained committed to reaching a collective bargaining agreement with the union.

Lindsay Spinney was born in the same hospital where she now works in the newborn intensive care unit. A 43-year-old registered nurse at Ascension Seton Medical Center—a 524-bed Catholic hospital in central Austin—Spinney has spent almost six years caring for babies born sick or premature, some so small their weight registers only in grams or ounces. It was her dream job.

Spinney had worked with kids for years as a nanny and teacher, and she grew up spending time in hospitals because of a sibling with disabilities. One day, she shadowed a nurse during a shift and knew instantly that she’d found her calling. Specifically, she wanted to work at Seton, a nonprofit whose roots lie with an order of nuns who moved to Austin more than a century past. After nursing school, she “applied there only; that’s the only job that I wanted.”

But reality at the hospital soon diverged from Spinney’s expectations. Above all, she found the place was understaffed, forcing her to split her time and attention between four fragile infants when she should be charged with one or two. Babies were often left to cry, even though all her training told her to respond immediately. “We’re starting with this blank canvas of this super-delicate being, and we’re not even able to provide the most minimal, basic things,” she said. Sometimes, visiting parents would notice and even offer to help with babies other than their own.

These staffing issues deepened after COVID hit, as veteran nurses left the hospital and were replaced by temporary travel nurses. The understaffing caused a stress at work that soon curdled into a gnawing guilt—a phenomenon that nurse advocates have taken to calling a form of “moral injury,” akin to the experience of soldiers. “It is not uncommon for a nurse to leave their shift and go sit in their car and cry,” Spinney said, as feelings of inadequacy pile up. “It also starts to provoke a lot of anxiety about your next shift. … It’s a really hard cycle to break.”

Last year, Spinney was on the verge of leaving what she’d thought would be her lifelong career. She’d earned a master’s degree related to healthcare leadership, a lifeboat to get her away from hospital bedsides before she drowned. But that’s when she learned her coworkers at Seton were starting the process of unionizing. “Being from Texas, I have very little experience or information with unions, with striking, with the labor movement,” she said. Nevertheless, she saw a chance to turn things around: She ditched her plan to leave and threw herself into the effort.

“It is not uncommon for a nurse to leave their shift and go sit in their car and cry.”

Hospital management opposed the union drive, but last September Spinney and her colleagues voted 385-151 to form the largest private-sector nurses union in Texas, joining the nation’s biggest nurses union: National Nurses United (NNU). Spinney hopes that move will ultimately enable caregivers like her to stay in their chosen profession. For seven months now, she’s been part of the team fighting for a labor contract to make that possible. It’s been slow going, and they’ve already had to call a historic one-day strike in a bid to make some headway against management.

Austin’s Seton hospital, though not run by nuns these days, does remain in Catholic hands: Since 1999, it’s belonged to St. Louis-based Ascension Health, the nation’s fourth-largest hospital chain and second-largest nonprofit chain. Ascension refers to itself as a “ministry” and emphasizes service for the “poor and vulnerable.” By dint of its nonprofit status, which commits the organization to serve the public, Ascension avoids some $1 billion a year in taxes. But recent reporting has called into question the chain’s fidelity to its mission.

In 2021, the news outlet STAT revealed that Ascension was running a “Wall Street-style” $1 billion private equity fund. In 2022, the New York Times reported the nonprofit paid its chief executive $13 million the prior year, had $41 billion in an investment arm, and maintained $18 billion in cash reserves—all after openly pursuing reductions in hospital staffing and lobbying against state-level bills mandating safer nurse-to-patient ratios. (In California, where nurses’ salaries also average about $50,000 higher than Texas, such a law mandates low ratios including 1:2 in newborn intensive care.) Being squeezed by such a profitable nonprofit motivated the Austin nurses to organize.

“They have a beautiful mission statement, and they regularly cite it, but they most definitely do not live their mission,” Spinney said about Ascension.

In the six months following the Seton vote, nurses at two Ascension hospitals in Wichita, Kansas, also unionized—part of what labor scholars call an ongoing trend.

“Over the last 20 years or so, nurses have been organizing at a faster rate than any other profession,” Paul Clark, a professor of labor relations at Penn State University, told the Texas Observer in an email. “The issue driving nurse organizing is a desire on the part of [registered nurses] to have a greater voice in patient care.”

In Texas, where just 5 percent of workers are unionized, the Austin election was a blue-moon event. The Seton union was the second-largest union of any kind to form in Texas via a National Labor Relations Board election in the last 16 years. (Many of the other largest elections in that time period stemmed from another hospital organizing campaign about a decade ago in South and West Texas.) Other recent groundbreaking unionizations have unfolded in anti-labor Texas at a trio of daily newspapers and a spate of Starbucks stores.

Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor of labor history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, attributes these developments including rising nurse militancy partly to degraded work conditions. But there has also been a “pro-union ideological shift of a very large layer of well-educated service sector workers, from baristas to museum workers, to grad students, to Hollywood writers,” he wrote in an email. “The pandemic discredited employers in many industries,” he said, adding that the phenomenon is taking place in the country’s North and South alike.

“Y’all are out here on strike making sure that our kids are born safely, that we’re taken care of when we are sick, that our neighbors—in their most desperate moments—get the care that they need.”

Since the union vote last fall, Seton nurses have been fighting for a labor contract, the main purpose of unionizing. Spinney is one of five members on the union’s bargaining team. Progress has been slow: “They have been dragging their feet,” she said. So far, the two sides have only reached tentative agreements on minor issues such as time off work to vote. They have not delved into the core issues that she says are key for nurses and patients: safer staffing ratios, better infectious disease protocols, a nurse-led advisory committee, and higher pay to help retain experienced Austin nurses—some of whom can no longer afford to live in Texas’ pricey capital. Excessive delay is a common tactic for employers in union negotiations.

Facing this glacial progress, the Austin nurses took another historic step. In late May and early June, the NNU said in a statement, Seton nurses voted near-unanimously to engage in a one-day strike, as did nurses in Wichita, setting up the largest nurses’ strikes in both Lone Star and Sunflower State histories. NNU says it represents about 900 nurses in Austin and about 1,000 at two Wichita hospitals. In response, Ascension announced it would bring in temporary replacement staff and striking nurses would not be allowed to return for another three days after the strike, which the hospital chain described as a requirement of its hired staffing agency but that nurses called a retaliatory move that could harm patients.

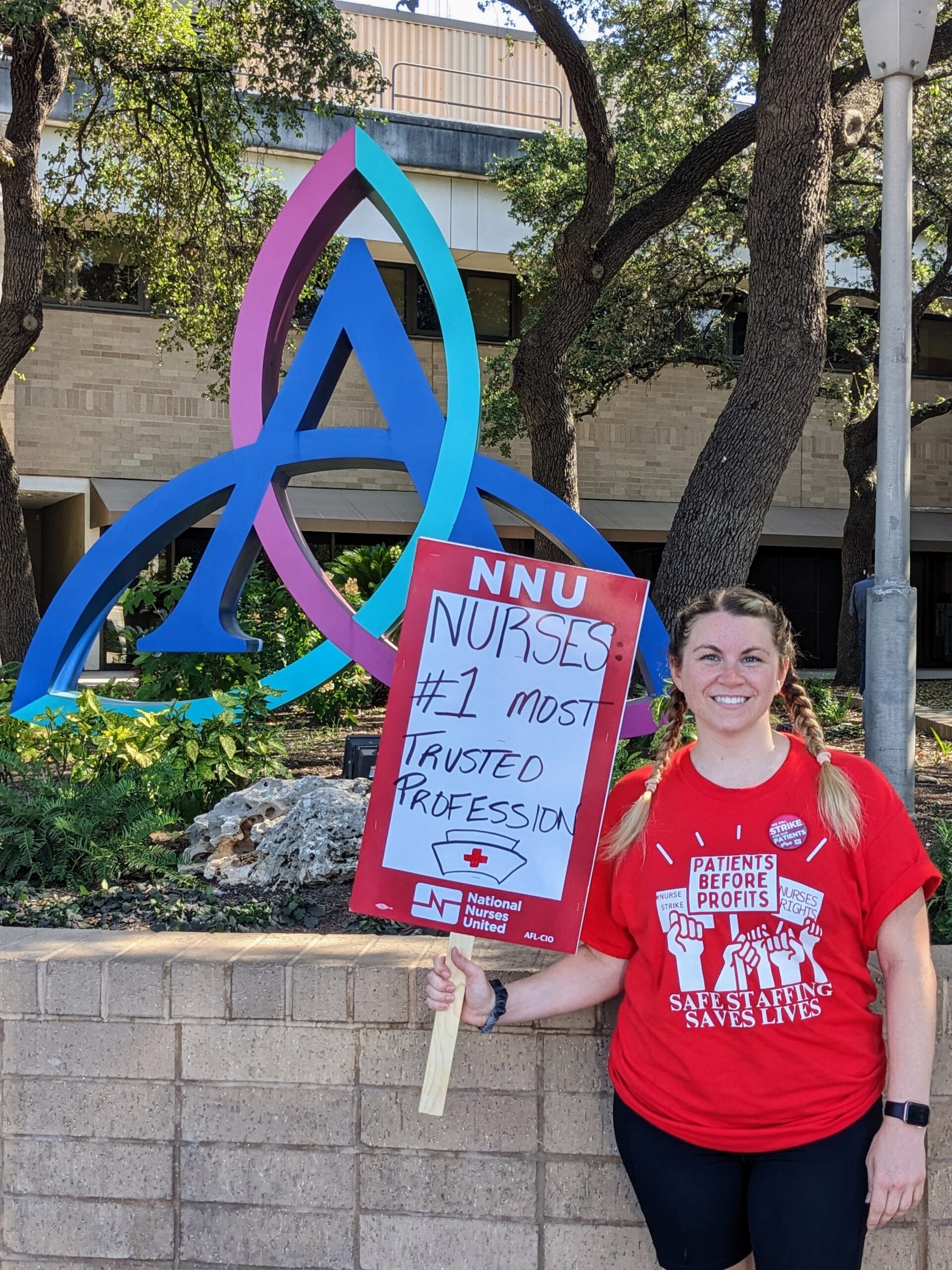

On the morning of June 27, despite historic high temperatures already cooking the city, a jubilant crowd of perhaps a couple hundred striking nurses and supporters took over the sidewalk and grounds along 38th Street outside Seton. Many wore scrubs or red shirts reading “patients before profits.” As they marched up and down the block, they carried signs reading “Heroes strike here” and “Ascension so full of [poop emoji] you need an enema.” Music blared, including “Respect” by Aretha Franklin and Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” They chanted “Hey hey, ho ho, corporate greed has got to go,” and “Don’t mess with Texas nurses.”

Longtime Texas labor organizers told the Observer they couldn’t recall a picket line so large and energetic.

Spinney served as MC during a set of scheduled speeches. Sandy Reding, a president of the branch of NNU that’s organizing in Texas, said the strike was “inspiring nurses throughout Texas to stand up and fight back and demand more of their employers, even those that like to hide behind their ‘ministry.’”

Congressman and ex-labor organizer Greg Casar, D-Austin, told the workers that they were adding a chapter to Texas labor history, noting that César Chávez had marched not far away as part of a furniture store strike in the 1970s. He emphasized that the nurses’ work stoppage would serve the whole community: “Solidarity is a word that we toss around a lot, but what it means is making a sacrifice for something so much bigger than yourselves. … Y’all are out here on strike making sure that our kids are born safely, that we’re taken care of when we are sick, that our neighbors—in their most desperate moments—get the care that they need.”

Austin state Representative Gina Hinojosa, also a Democrat, identified gender discrimination in hospitals’ treatment of nurses. “It just so happens that the workforce here … [is] thought to be predominantly doing ‘women’s work,’” she said. “So do you think it is a coincidence that your voices and your opinions are discounted in favor of businessmen when you are the professionals who know what we need?”

Among the many striking nurses was Jessica Gripentrog, 32, who’s worked about three years in Seton’s so-called float pool, a sort of flex position that requires rotating among understaffed units. She said she’s seen an urgent loss of expertise as veteran nurses have been replaced by new and temporary travel nurses. Specifically, she said she was trained last year in an intensive care unit by someone who’d only been a nurse for six months. Gripentrog wound up having to teach her supposed trainer. “You start to see this trend on the units where all of the nurses are new nurses, and this can be a dangerous situation,” she said.

Gripentrog said she believes Ascension is basing decisions on money rather than patient safety. “I’m a Christian,” she said, and “when you think of a Catholic hospital and what a good Christian might represent, it seems like it represents the opposite of what Ascension is.”

In a statement to the Observer, an Ascension spokesperson wrote: “While as a ministry of the Catholic Church we affirm the right of our associates to organize, we are disappointed that National Nurses United made the decision to proceed with a strike, especially given the hardship this presents for our associates and their families, and the concern this action may cause our patients and their loved ones.”

The spokesperson said there would be “no disruption in service” and reiterated that the company was contractually obligated to employ its temp replacements for four days, so striking nurses could resume shifts only after that period. The spokesperson did not answer other detailed questions.

Early on the morning after the strike, nurses arrived at the Seton hospital anyway in an attempt to work and care for their patients. As Ascension had promised, they were turned away.