Near the grand bazaar in Tehran, over the entrance to the complex housing the ministries of foreign affairs and information, the national museum and the Islamic era museum, is a colourful mural, dating to the time of Reza Shah, depicting symbols of Iranian nationalism including a dignified soldier, a Maxim machine-gun, and crossed Iranian flags.

The flags, sporting the distinctive horizontal bands of red, white and green, have been more recently altered than the rest. On all the flags, the white band in the centre has been painted over with a fresh coat of eggshell white. On the green band below you can see, cut off at the ankles, the paws of a lion and on the red band above you can see the rays of a rising sun.

These are remnants, spared a literal-white washing, of the Shir o Khorshid, or Lion and Sun, a coat of arms that graced the Iranian flag from the mid 19th century until the 1979 Revolution when it was replaced by a stylized version of the word Allah (“God”) written in Arabic script.

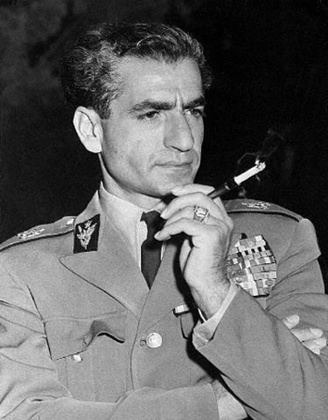

The Shir o Khorshid, a popular Iranian symbol since at least the 12th century, has since the revolution become associated with the deposed monarch Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and his dynasty. After the revolution, the new government of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini systematically eradicated it from public spaces and government buildings, replacing it with Islamic iconography. Today in Iran nostalgia for the Shah and his government, like the paws of the lion, peeks out from under a coat of white paint.

When I visited the Vakil bazaar in Shiraz or the Jomeh bazaar in Tehran, I saw mountains of Shah-related memorabilia at almost every stall. Vintage Iranian rial notes and postage stamps emblazoned with his face, brass busts of him and his infamously fabulous wife Empress Farah, coffee-table books with full-colour photos of the royal family, countless pendants, rings, and wall hangings depicting the Shir o Khorshid, some vintage and some obviously mass-produced more recently.

Displaying or selling the Shir o Khorshid is technically illegal in Iran, but many shopkeepers told me the police aren’t enforcing the law as much as they used to. “It’s definitely much safer now,” said Mohammad, 68, who owns shops in the grand bazaar in Tehran, and the Vakil bazaar in Shiraz. “There was a time when you couldn’t have that symbol anywhere.”

“You can sell them and they won’t bother you,” said Reza, 39, another shopkeeper in Tehran’s grand bazaar. “As long as you don’t make a big deal out of it. You can’t put a flag right out in front of your shop. ”

I bought a Shah-era five-rial coin, engraved with the lion and sun, and I wear it on a silver chain around my neck. It constantly draws comments from people during my daily commute. Once, a man selling socks on the metro came up to me when he saw it.

“God bless his soul,” he said, pointing to my necklace, “I was 11, I remember. The first 11 years of my life were great, the rest have been terrible. I ate good food for the first 11 years and then crap.” He grabbed my collarbone with the firm nerve pinch that some Iranian men use to show affection. “God bless his soul. Don’t lose that.”

Another time, in Shiraz, a bus driver when he saw it delayed everyone 15 minutes so he could expresses in verbose, glowing terms, his love of the Pahlavi family, “They were strong, they came from good blood, from a good tribe, ” he said to me, raising his extended index finger higher and higher into the air as he spoke. “They were powerful, they were able to get things done.”

I was taught in my history classes that the Shah was a tin-pot dictator installed by the CIA to subdue Iran’s leftists and secure American access to the country’s oil. That he was extravagant and capricious. That his secret police, the Savak, tortured and spied with impunity.

Much of this is probably true. Mohammad Reza was definitely the intended beneficiary of an at-least-attempted CIA coup in 1953. And he was definitely a dictator (though whether he was benevolent or tyrannical is debatable).

But I must admit to ambivalent feelings towards the Shah and his government. Under the Shah my grandmother gained the right to vote and to divorce her emotionally abusive, opium-addicted husband. My relatives benefitted from his land redistribution and industrial profit-sharing programmes. My father learned to read from the Shah’s literacy corps and received government-subsidised meals and textbooks.

So who am I to tell them that he was a lousy guy, that he was a despot, that his policies were too pro-western? They don’t care about that. They were starving and he gave them food, that’s all they need to know. In my household I was always taught that Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his father were the greatest leaders Iran ever had. My family loves the man like a grandfather, or even a god. Growing up, we always had a Shir o Khorshid in our house.

“Every aspect of life was better then,” my father loves to say, “everyone was happier.” When he comes to visit Iran he blames every imperfection personally on Khomeini. The teller at the bank is rude? Khomeini. The metro is late? Khomeini. The internet is slow? Khomeini. When he was growing up, people were nicer, food tasted better, the Azadi Tower looked bigger.

When I try to introduce any nuance into his interpretation of history, to suggest that perhaps life wasn’t better for everyone under the Shah, for instance those who were having their eyes pulled out by the Savak in Evin prison, he completely shuts down. “I can’t talk to you about it, because you weren’t there.”

The appeal of the Shir o Khorshid pendant for me is complex and multilayered. On the one hand, the lion and sun motif is perhaps the only symbol that has ever encapsulated the many facets of the Iranian identity. In its design you can find Zoroastrian, Islamic, Jewish, Turkic, and Zodiacal influence. It was used by every dynasty for 800 years, including the Safavids, Qajars and Pahlavis.

On the other hand, the necklace is a simple tribute to my father and his singular, uncompromising view of the world. There’s also of course a stylistic appeal: I mean, what’s cooler than a lion holding a sabre standing before the rising sun?

And of course I must admit to an intrinsic love of things that are vaguely subversive. I love walking around knowing that I’m wearing something illegal. I love the raised eyebrows and knowing winks I get when people see it. I love asking a soldier for directions knowing that I’m displaying the standard of the vanquished on my chest. It just appeals to my contrarian ethos.

Recently I was at my uncle’s apartment in Tehran. He was watching a documentary about the Shah on illegal satellite TV from Turkey. The narrator was talking over stock footage of how the Shah’s health corps eradicated malaria in the countryside, of how he modernised Iran’s rail infrastructure, of how he took its natural resources back from foreign interests.

“Everything that is functioning in this country today is because of him and his father!” my uncle said to no-one in particular. He turned to me: “Before the Shah, your grandfather used to have to go fight people, with guns and knives, just to get a bucket of water for his family to drink. The Shah made sure that everyone had clean water.” A presenter in suit and tie appeared on the screen, sitting in front of the pre-revolutionary flag and a statue of a lion.

“In the Shah’s time, when I went to Italy, they stood up for me, they talked to me with respect,” the presenter said, slamming his fist on the table. “When I went to France they respected me as an Iranian. Now when I go anywhere in the world they think we are terrorists, they think we are barbarians.”

Pictures of the Shah came across the screen, set to a triumphal march. Pictures of him with the royal family, of him attending state dinners with Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter, surveying a public works project somewhere. “For 37 years during his rule,” the presenter said, “the price of the dollar didn’t change at all. In 1979 the exchange rate was 70 rials to a dollar, now it is 33,000 rials to a dollar.”

“He was a great man,” said my uncle, “these stupid mullahs have set us back 1500 years.”

Nostalgia for the shah among those who actually remember him is at least intelligible. What took me entirely by surprise is that even among those born after the revolution, the Shah has taken on almost mythic status. I was hanging out in front of the Artists’ Forum near the old American embassy - a popular place for hipsters, artists and intellectuals.

I was talking to a guy in his mid to early twenties who was selling bootleg Lars Von Trier DVDs. He noticed my necklace and got very excited. He called it mashti, an old Farsi word for someone who has made the pilgrimage to Mashhad but which young Iranians use to mean cool. “He was a great man,” he said, “it was a much better time for everyone.”

Another time I struck up a conversation with a skate boarder in Laleh Park and he noticed it. “These fucking mullahs man, they don’t give a fuck about us,” he said. He had a septum piercing and tattoos up his right arm. “The Shah cared about his people. He was a real leader. ”

“I can’t say anything for sure, but what I know is that he was far better than the current government,” said Amir, a 26-year-old English teacher who was arrested and tortured for participating in the Green Movement protests after the disputed 2009 presidential election. “All governments are dictatorships, but you can judge them based on the situation of society and the country during their rule. Most of the development that happened in Iran happened under him and his father. And least he was Iranian, I know that much. He wasn’t Arab, now Arabs control the government.”

Revisionist history in an oppressive theocracy is not surprising. What’s unusual about this zeal for the Shah is that it’s revising in favour of the government that lost, the government that was called decadent and corrupt and swept into oblivion by a wave of populist fervour.

What’s more, admiration for the Shah is almost always expressed to me in diametric opposition to the current regime in Tehran. No one ever seems to calls the Shah good, they call him better than. Better than now. Richer than now, fuller than now, more comfortable than now. More fun than now. The Shah drove around in luxury Cadillacs, in tailored suits and Ray Ban sunglasses. His wife was the Jackie O of the east. When he celebrated the 2500th anniversary of the Persian empire, he flew in the finest chefs from Paris to prepare breast of peacock for royalty and world leaders. He pedalled an intoxicating fantasy.

In his time, Lalezar Street was filled with cabarets, night clubs, bars. Packed most nights until morning. Googoosh, Ebi, Dariush, all the greats played there. The women wore tight skirts and let their hair flow and get tussled. Today Lalezar is filled with shops selling expensive chandeliers and it’s dead by 10pm. The Crystal Cinema still sits there, boarded up and laconic - a constant reminder that the party is over and no one’s cleaned up the mess.

Iranians don’t seem to remember the Shah as he was, but as they need him to have been. They need to remember a time when everyone was drunk and in love, cruising the streets on the backs of Vespas, with Serge Gainsbourg wafting through the air and the bar not closing for hours. It’s a seductive dream and a potent antidote to the creeping malaise of life in the Islamic republic.

People need to believe that there was some time better than now. Better than bootleg arak out of a water bottle with the same five people every Wednesday night. Better than constantly worrying about breaking one of the arbitrarily applied rules that govern every part of life in Iran. Better than hijab in the summer time, and the morality police, and being afraid to dance in the street.

The Shah’s main appeal is that he’s the exact opposite of everything the Islamic republic represents, he’s all for rock and roll and miniskirts and stiff drinks. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi has become a repository for people’s pent-up anger and frustration, a canvas on which to paint a better version of Iran – even if it’s one that never really existed. It’s nostalgia as subversion.