For the past few months, farmers protesting in India’s capital, New Delhi, have been demanding the repeal of three farm laws that were passed last year. These largely peaceful protests have been referred to as a “satyagraha” by many in the Indian media, politicians and activists.

As a political scientist who writes on Indian politics and society, I argue that the choice of this word, which means “embracing the truth,” is important to note.

It evokes a long political history that goes back to the Indian nationalist movement against British rule.

The first satyagraha

In 1917, Mahatma Gandhi, one of the leading icons of the Indian nationalist movement, started a political protest in the village of Champaran in what is today the eastern state of Bihar.

The movement was on behalf of poor farmers who had been forced to grow indigo used in the making of dyes. The British colonial authorities who saw this as a lucrative trade coerced the farmers into growing the crop even as they were poorly paid. If the farmers refused, they were heavily taxed.

Gandhi organized a nonviolent protest on behalf of the farmers. That was when the word satyagraha was used for the first time in the context of a political protest.

The use of this form of protest was both ethical and instrumental. The moral dimension sprang from Gandhi’s convictions. The practical element had to do with the realization that violence against the might of the British colonial empire was counterproductive.

Gandhi had first arrived at the idea of using nonviolent protest as a tactic in his early years as a lawyer in South Africa, where he was concerned with the maltreatment of the Indian community under British rule.

The concept of satyagraha was in turn drawn from his extensive reading of the works of the British poet and social critic John Ruskin, the Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy and the American philosopher Henry David Thoreau.

Gandhi melded their ideas into what he had learned from the ancient Jain faith about the concept of “ahimsa,” which involves minimizing harm to all living beings.

Dandi march

In Gandhi’s view, and that of his followers, satyagraha involved a passionate commitment to nonviolent civil disobedience. To that end, he and his followers not only shunned all violence but steadfastly fought against social injustices.

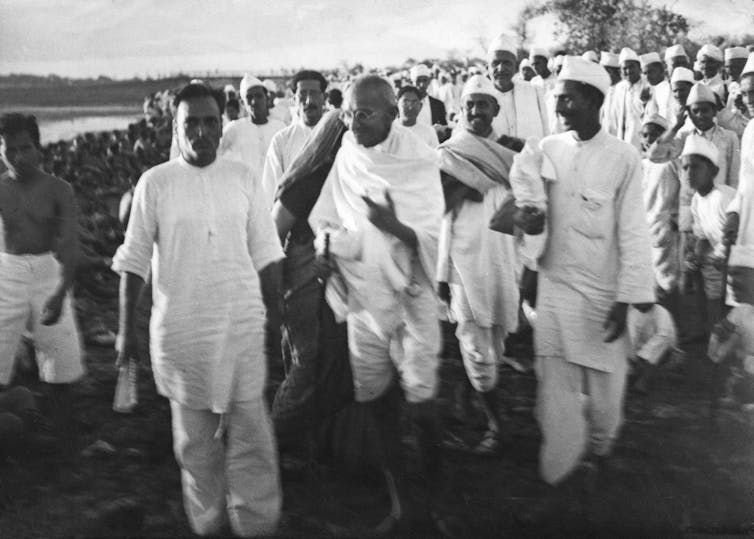

Gandhi used the concept effectively in a protest against the colonial salt tax laws.

The Salt Law under colonial rule had prohibited the private production of salt, forcing Indians to buy this vital dietary staple at high market prices set by the British.

In 1931, Gandhi organized a march that went across much of the country to the seaside town of Dandi, in the western state of Gujarat. In a gesture of defiance to the Salt Law, Gandhi and his followers picked up natural salt from the beach as a way to demonstrate that they had a right to produce their own salt.

The British colonial authorities met this resistance with considerable violence and imprisoned Gandhi along many of the protesters. However, Gandhi and his supporters refused to back down. They conceded that they had broken the law by collecting salt from the seashore and were prepared to suffer the legal consequences.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

The memories of this episode have become part and parcel of the history and folklore of the Indian nationalist movement. Accordingly, it is hardly surprising that the protesting farmers embraced the concept of satyagraha as part of their protests.

For over six months they have led protests as a tactic and have steadfastly refused to budge from their principal demands, which involve repealing the three new farm laws that the Indian Parliament passed in September 2020 which, if implemented, would dramatically cut back on government support for agriculture and move farmers toward an open national market.

Farmers fear these drastic changes and, despite government entreaties as well as crackdowns, they have refused to budge.

Sumit Ganguly receives funding from the U.S. Army War College.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.