His fellow villagers were bewildered.

In the orange orchards, on top of a hill on the outskirts of their small scenic town, they saw a man in a cowboy hat standing on a rock, talking passionately at his smartphone screen for hours.

Two years on, many are joining in.

Zhong Haihui, a 40-year-old farmer, was one of the first people in Hunan province to start selling his fruits through live streaming. Now he's just one of many live streamers in rural China doing the same, reaching millions of customers from across the country on short video app Kuaishou and ecommerce app Taobao.

(Abacus is a unit of the South China Morning Post, which is owned by Alibaba, owner of Taobao.)

Zhong is more talkative and energetic when he's chatting to his followers online. Chubby and smiling like a buddha, he refers to himself as "Uncle,'' a nickname that his viewers gladly use.

He also cordially calls his viewers "bao bao" -- literally meaning "baby" in Chinese. It's a common way Taobao live streaming hosts address their viewers to appear friendly and build rapport.

"Welcome, new babies! Tap follow if you haven't! Follow Uncle and there will be more tasty food later!"

That's a line he goes back to almost every other minute. For the rest of the time, he restlessly promotes his tasty, fresh fruit, points his camera at the surrounding mountains, and occasionally hums a random tune or asks viewers if they've eaten.

A popular tourist destination of a little more than 1.4 million residents, Zhangjiajie is famous for its craggy mountains, including some peaks that bear a striking resemblance to those in the blockbuster 2009 movie Avatar. Trying to cash in on the movie's success, local officials drew backlash in China in 2010 when they decided to rename one of the mountains the "Avatar Hallelujah Mountain."

Born and raised in the town, Zhong worked at a gas station and in a factory before opening an ecommerce shop on Taobao in 2011. Selling local farm products, his sales didn't take off until late-2017, when he discovered live streaming.

That's because apps in China tend to do everything. It's normal to shop in a short video app like Kuaishou, or watch live streams in a shopping app like Taobao.

Taobao and Kuaishou both said they don't yet have official numbers for how many farmers are selling products through live streaming on their platforms, but they're both pushing to cultivate more farmer live streamers.

Taobao said it aims to "incubate" 1,000 farmer live streamers in 100 counties in 2019, helping each of them earn more than 10,000 yuan (US$1,400) in monthly income. And Kuaishou said there are 1.15 million rural users selling local products on its app through both short videos and live streaming. They earned 19 billion yuan (US$2.75 billion) altogether in 2018, according to Kuaishou.

Another reason for the rising interest is rising concern over food safety in China, so people tune in to see the places their produce comes from.

We visited right before Chinese New Year, when all couriers had suspended operations for the holiday. Zhong had also temporarily stopped live streaming and shipping his fruits.

Zhong and Xiaoqiang, his 21-year-old business partner, started an unscheduled live stream at around 10am. Hundreds tuned in within a few seconds.

In turn, the two hosts busily addressed almost every single comment popping up on his phone, most of which asked about what fruits they were selling that day or when they would resume business. Some comments simply offered holiday greetings to the two hosts. When Zhong said he had to sign off in a few minutes, viewers tried to keep him online.

"Don't leave, Uncle. Stay and chat!" Zhong laughed as he read the message.

Zhong has been expanding his business on Taobao by partnering with local orchards around the country. He plans to live stream and ship fruits from the places he partners with. He also wants to become a live-streaming tour guide since his city is full of popular travel destinations.

China saw explosive growth of live streaming in 2016, when the market was valued at 20.8 billion yuan (US$3 billion), a 180% increase over the previous year. Tech companies were raking in billions by taking cuts from tips given to streamers by viewers.

But the industry started cooling recently because of waning user interest and stricter online censorship. In 2018, China had 396.76 million users of live streaming, a 6% decline from 2017, according to an annual internet report by CNNIC. It was the only online service category that saw a decline in users that year. (Users of online ride hailing, in contrast, grew 40.9%.)

As people lose interest in watching typical streamers sing and dance, the focus seems to be switching to more off-beat streamers like farmers. It seems that viewers in big cities are intrigued by the village lives shown by rural live streamers.

Early on, Kuaishou was the subject of controversy for being full of videos showing rural users' crude and silly stunts. Now it seems people are happy to tune in and even buy products from people in remote areas of China.

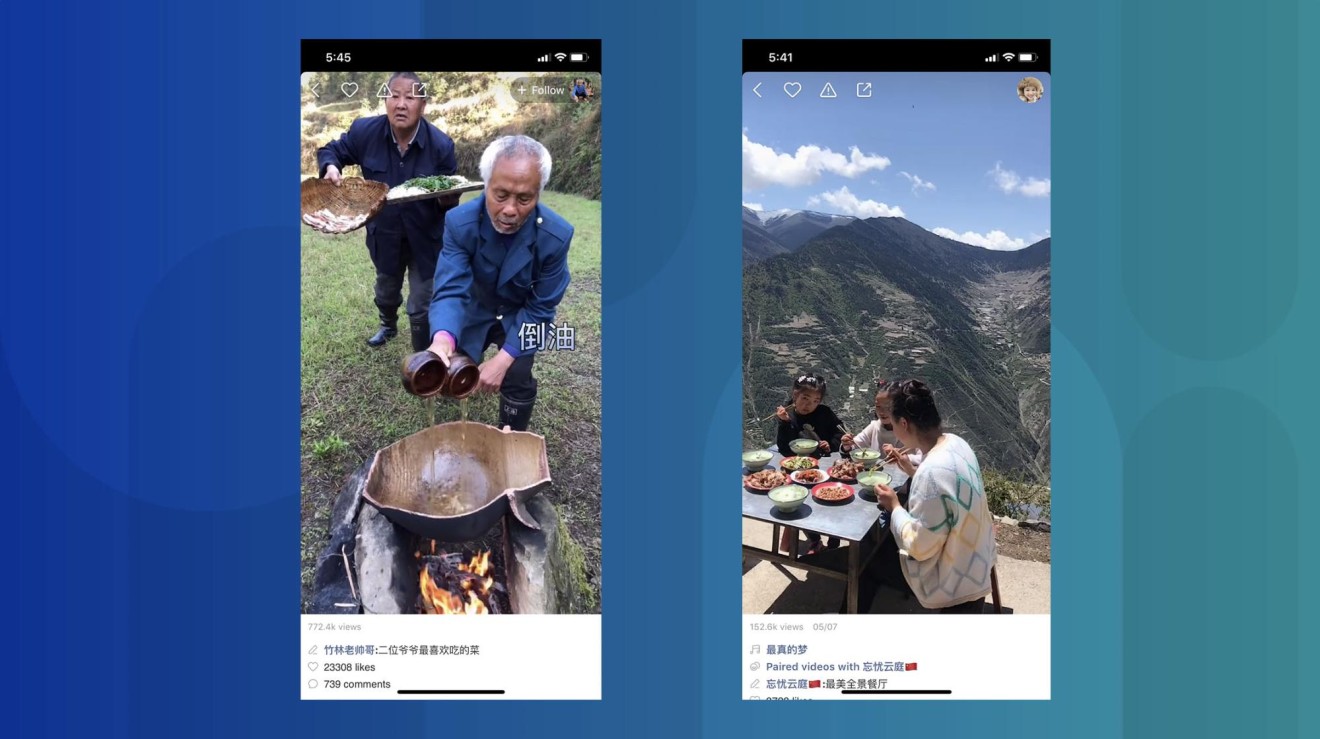

There are girls in Guizhou villages posting videos of cooking in the mountains, families living on the Sichuan Tibetan highlands having family dinners on the edge of a cliff, and small-town men producing Avengers parodies. Many of them have shops on Kuaishou selling local products.

Zhong's channel now has more than 82,000 followers. But it was no easy feat to get there, especially for someone who isn't used to being on camera or familiar with internet culture.

"Everything felt awkward when we first started," Zhong recalled when driving us out of the town to his orchard. "It was so difficult to start calling people 'baby,' especially since I'm not young anymore. But we see that everybody else is doing it."

Zhong said he and Xiaoqiang would spend a lot of time watching other streamers and replays of their own live streams. Then they'd talk about how to do it right, sometimes until 2am. And that's after 10 hours of live streaming every day.

"Coming home from a live stream, I usually don't want to say a word anymore," Zhong said. "I've run out of things to say."

For more on China tech visit abacusnews.com or subscribe to our newsletter via abacusnews.com/newsletter for the latest China tech news, reviews and product launches.

Copyright (c) 2019. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.