The sporting mega-event often held up as a cautionary tale for prospective hosts is the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal. In 1970, the moustachioed Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau confidently declared: “The Olympics can no more run a deficit than a man can have a baby.” Several years and $1bn (£580m) of debt later, a cartoon in the Montreal Gazette depicted a pregnant Drapeau telephoning an abortion clinic.

Montreal finally paid off its Olympic debt in 2006. The corrupt and chaotically organised Games were a financial disaster and marked the start of an era of excess and overpromise, when Olympic bids became more and more extravagant: bigger and better, bigger and better. Increasingly, hosting international sporting events like the Olympics, the Fifa World Cup and the Commonwealths has become a gamble – cities must weigh up the vast and often uncontrollable costs against the benefits of a two-week economic boom, some investment in sporting facilities and infrastructure, and intangibles such as a boost to local pride.

The monetary gamble rarely pays off. India apportioned $250m for the 2010 Commonwealths in Delhi; they came in at $11bn, the most expensive in history. Olympic Games average almost double their initial budget. And so when Daniel Andrews, the premier of the Australian state of Victoria, cancelled plans to host the 2026 Commonwealth Games on Tuesday, perhaps he was taking a decision before it was too late to back out.

“What’s become clear is that the cost of hosting these Games in 2026 is not the $2.6bn which was budgeted and allocated,” Andrews said. “It is in fact at least $6bn, and could be as high as $7bn.”

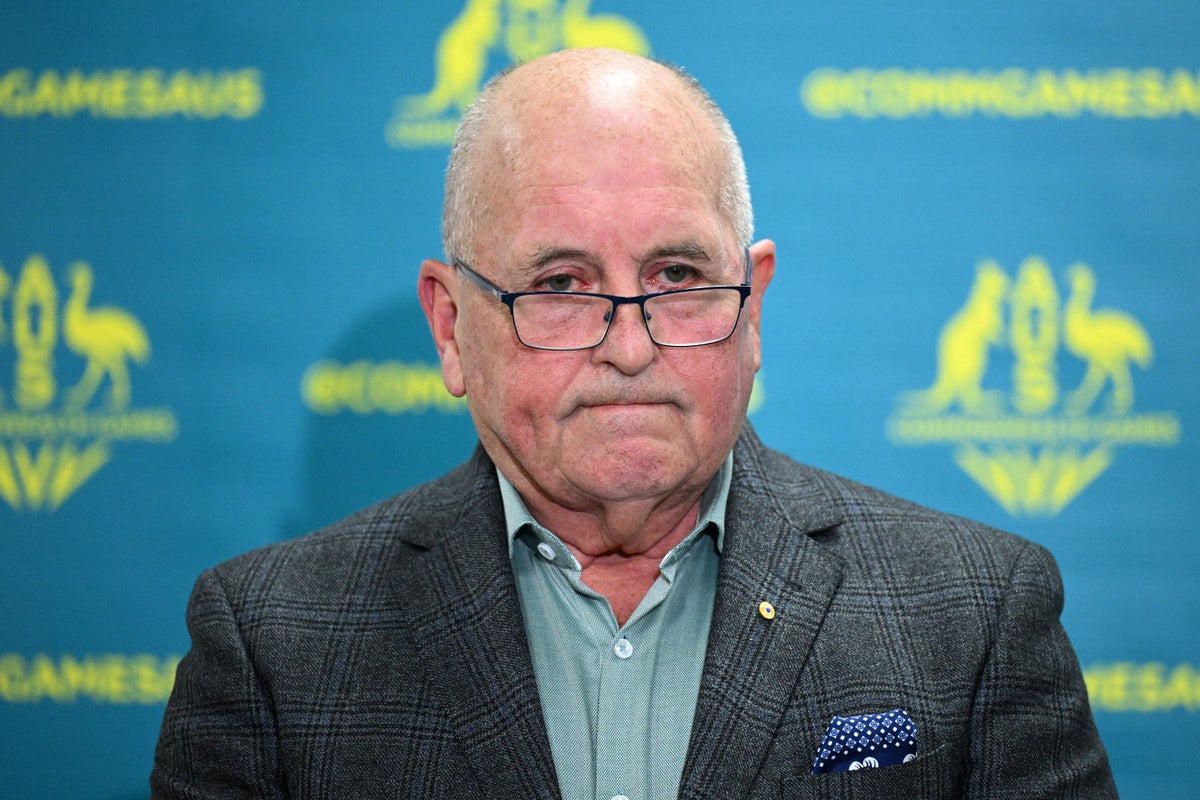

Victorian state premier Daniel Andrews announcing the news— (AP)

The sudden termination sparked a spat. The Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) replied by accusing him of “gross exaggeration”, claiming he had cited costs of $4bn in a meeting only last month. The CGF was also angry to have been given only eight hours’ notice before the announcement was made.

Andrews’ political opponents declared a “humiliation” for the state of Victoria, while Commonwealth Games Australia CEO Craig Phillips claimed the state government had “wilfully ignored recommendations to move events to purpose-built stadia in Melbourne and remained wedded to proceeding with expensive temporary venues in regional Victoria”.

The internal politics suggest that this is not just a financial decision, but about popularity, too. Hosting major sporting events is increasingly unpopular among local populations who are wise to the costs, and politicians are reluctant to become the face of a debt-laden Games. When bids are put to the populace, they are consistently rejected. In 2018, the people of Calgary voted “no” in a referendum on staging the 2026 Winter Olympics – the 11th successive city to vote against hosting an Olympic Games.

The Commonwealths’ bidding process currently conjures an image of a very unenthusiastic game of musical chairs. Victoria only stepped in late because Birmingham had to be moved from 2026 to 2022, to replace Durban, which had failed to make its finances stack up. Durban was only a back-up choice, replacing Edmonton, which quickly ran out of funding and had to withdraw.

A Commonwealth Games should, in theory, be cheaper than an Olympics, but the finances are still difficult to stack up. An independent report commissioned by the UK government found that the 2022 Games in Birmingham contributed more than £870m to the UK economy, which is roughly what it cost, a rare balancing of the books when most cities around the Commonwealth are not so well prepared to host.

Birmingham hosted the previous Commonwealth Games in 2022— (PA Archive)

The reputational benefits of playing host are complex in the modern world. The Commonwealth Games are sometimes referred to as the Friendly Games, but that does not disavow their imperial roots. That history will only be highlighted by the centenary edition coming in 2030, marking 100 years since the first, when they were called the British Empire Games.

The CGF’s website declares that the Commonwealth is beginning an “era of renewed relevance”, whatever that means. In reality, it is an event that feels lost in the 21st century. Last year, Tom Daley criticised the raft of countries involved that still outlaw homosexuality. In sporting terms, it is hard to explain why we need to know who is best at coastal rowing among some British territories and former colonies.

And so the appetite to embark on such a project is increasingly limited. It is financially risky and politically dangerous. As Andrews explained on Tuesday: “We are simply not going to invest that sort of money and take it from ... other parts of government in order to deliver a 12-day sporting event.”

With only three years to go, there is no obvious taker for the 2026 Commonwealths. Rather than kickstarting a fight to own the first Games since King Charles III took the throne, Victoria’s announcement has seen other locations line up to rule themselves out. New Zealand won’t be hosting; Sydney is not interested; Melbourne can’t make it work. Across Australia, state governments have said no. At such short notice, only a major city with existing infrastructure – most likely in the UK or Canada – could step up to avoid the Games being cancelled entirely for the first time since the Second World War.

And even if the 2026 Games is rescued at the last, the CGF’s problems are far from over. The Canadian city of Hamilton’s bid for 2030 has already collapsed: there is still plenty of time for the Centenary Games to become a bigger, better game of pass the parcel than those before it.