The koala is a much-loved species and lucrative tourism drawcard. Yet, for all its popularity, koalas are forecast to be extinct in NSW within 30 years.

Understanding the koala-human relationship might go some way to saving the species. My research examined the dynamic by tracing the representation of koalas in natural history books, children’s stories, postcards and tourism brochures.

I found that “anthropomorpism” – attributing human qualities to a non-human animal – has helped shift attitudes towards the koala away from the scientific and economic to a more romantic, emotional view. In particular, koalas share physical characteristics with human babies, which further endears them to us.

Anthropomorphism can trigger positive emotions in humans which helps with conservation actions. Ultimately, however, threats to koalas are the result of political decisions in which sentiment plays little part.

Seeing ourselves in koalas

When humans see themselves in other animals, this can engender greater empathy and concern for the species. And the koala, with its human baby-like qualities can be readily anthropomorphised.

Indeed, koalas exhibit “neoteny”, whereby mature animals retain juvenile physical features. This has been shown to trigger positive emotional responses from human adults.

These features include:

- a prominent forehead with eyes positioned below the centre of the head

- rounded head and body

- soft elasticity of the body surface

- a vertical posture.

Newspaper articles published in the first half of the 20th century often infantilised koalas. For instance, an article in the Glen Innes Examiner refers to koalas as “little bears” that sit “up like babies in the trees”.

Koalas even make a crying sound when hurt or upset, adding to their baby-like qualities.

A scientific curiosity

Koalas have not always endeared themselves to post-colonial Australians.

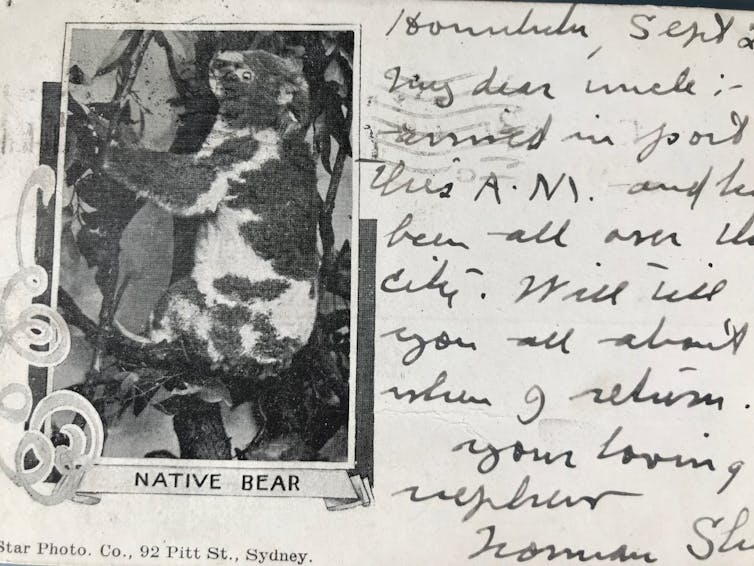

European settlers sought to understand the animal with frames of reference available at the time. As such, the earliest accounts of the koala variously referred to it as a monkey, a sloth, a lemur and a bear.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Australians viewed the koala predominantly through a detached, scientific lens. Scientific illustrations and paintings were made of koalas, and information and images were published in natural history and zoology publications.

At the same time, the koala was also seen as an economic resource. From the early 1800s until the 1920s, hundreds of thousands, if not millions, were slaughtered for the fur trade.

Into the 1900s, zoological representations of the koala continued to be published in natural histories. They included Le Souef and Burrell’s The Wild Animals of Australasia, published in 1926, which stated:

The quaint koala, or native bear, a creature which, perhaps, holds the affection of Australians more than any other of their wild animals – a fact for which its innocent, babyish expression and quiet and inoffensive ways are largely responsible.

This passage indicates a shift towards a more romantic view of koalas as akin to humans.

The love affair

Two books published in 1918 encouraged public affection for koalas. Norman Lindsay’s The Magic Pudding, featured an anthropomorphised koala character called Bunyip Bluegum, who wore smart slacks, a jacket and a bow tie. May Gibbs’ Snugglepot and Cuddlepie also included friendly koalas.

The books reached a far wider audience than natural histories. They helped fuel outrage when the open season of koala hunting was declared in Queensland in 1927.

The emergence of the very popular Blinky Bill koala character in 1933 helped further humanise the species.

The rapid rise of photography in the 20th century also helped cement koalas’ public appeal. Groups of koalas were arranged for photos to be reproduced as postcards, often captioned “Australia’s teddy bear”.

Zoologist Ellis Troughton, in his landmark 1931 book Furred Animals of Australia, recorded the special place koalas occupied in the national psyche:

This attractive and rather helpless orphan which has become world famous in caricature and story, holds the affection of fellow Australians more than any other animal of their adopted country.

The popularity of koalas fed into an emerging tourism industry eager to create national distinctiveness in the global tourism market.

Today the koala’s image is still reproduced on tea towels, t-shirts, postcards and other souvenirs. Pre-COVID, the economic value of the koala to Australian tourism was estimated at up to A$3.2 billion a year.

Unlike other native species, koalas now have their own dedicated “hospitals” in three states. At the time of writing, a crowd-funding campaign for the Port Macquarie Koala Hospital, set up after the Black Summer bushfires, had raised almost A$8 million.

And koalas attract far more government funding than most species. For example, research last year showed conservation funding for the koala far outstripped that for the northern hairy-nosed wombat. The wombat is listed as critically endangered while the koala is off less conservation concern – listed as vulnerable in parts of Australia.

Read more: Scientists find burnt, starving koalas weeks after the bushfires

Saving what we love

Anthropomorphism can be a powerful way to generate concern and action for a species. However, there are limits to its effectiveness.

For all their popularity, koalas face extinction in NSW within 30 years. Estimates of the wild national koala population vary from 140,000 to 600,000.

It might seem baffling that such a well-loved animal could be headed for extinction. But the koala’s continued survival depends on political decisions where emotion and public sentiment are so often overridden by economics and vested interests.

Australians clearly care deeply for their koalas. But that sentiment must translate into collective political pressure if the species is to survive.

Read more: Stopping koala extinction is agonisingly simple. But here's why I'm not optimistic

Kevin Markwell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.