Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why do we bleed? – Michael, age 9, Seattle, Washington

“Ouch!” I cried out, looking down at where my family’s puppy, Hercules, had just bitten me. Two tiny dots of red started to bloom where he had sunk his canine teeth into my finger.

“Bad dog,” I said to him. He looked up at me sheepishly. “Well, I guess I’m a bad human for putting my finger near your mouth,” I admitted. He wagged his tail and licked my arm.

I put pressure on my finger until the bleeding stopped. Three weeks later the area had healed, and we had taught Hercules to heel, too!

I am a doctor who specializes in hematology – the study of blood. Here, I’ll share with you how blood travels through the body, how we bleed and, more importantly, how we stop bleeding.

What’s inside blood?

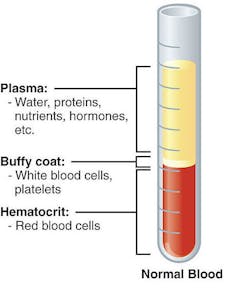

The blood in our bodies is a complex fluid. It contains red blood cells, which bring oxygen to our body’s tissues; white blood cells, our body’s infection-fighting army; and platelets, which clump together to help stop bleeding. A special protein called hemoglobin in red blood cells is what gives our blood its beautiful red color.

The yellowy, liquid portion of blood is called plasma. Most of it – over 90% of it – is water, but the remaining portion contains molecules that help our blood clot and stop bleeding.

Where does blood live and where does it travel?

The bone marrow, located in the center of our bones, is the factory that makes the cells circulating in our bloodstream.

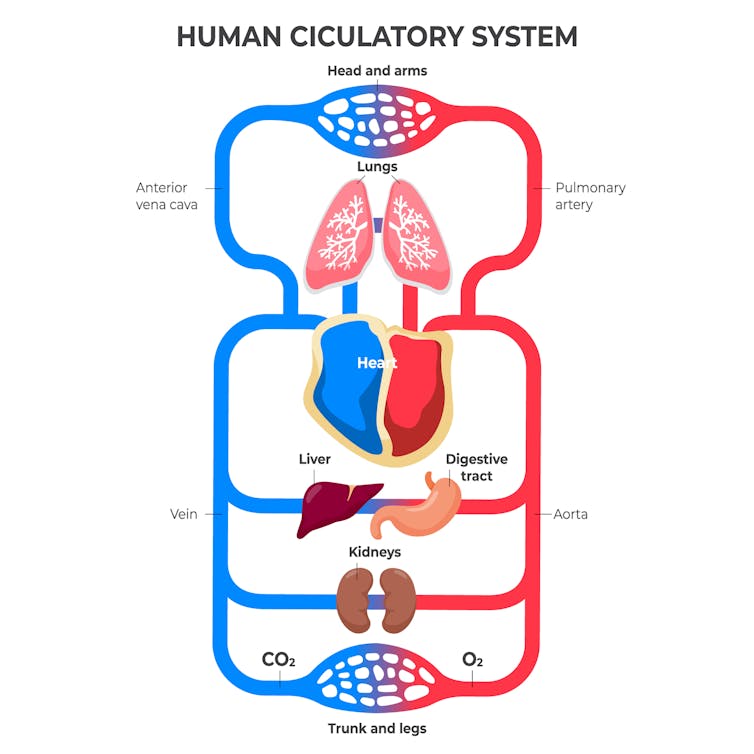

Once blood cells are made, they move into blood vessels – rubbery tubes that form roads traveling through our entire body. Veins are the vessels that carry blood to the heart, while arteries carry blood to the rest of the body. The biggest vessels can be the width of a garden hose, while the smallest can be tinier than a human hair. Blood travels 12,000 miles through the vessels of an adult every single day!

The heart is the powerful engine that pushes blood through those tubes to deliver oxygen and nutrients to our organs and skin. First, the right side of the heart pumps the blood into the lungs, which contains oxygen from the air we breathe. Here, the hemoglobin in red blood cells grabs oxygen and take it back to the heart.

The left side of the heart then pumps that oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. After red blood cells drop off their oxygen cargo, they are pumped back to the right side of the heart to get more oxygen and repeat their tour of the body again.

Why do we bleed?

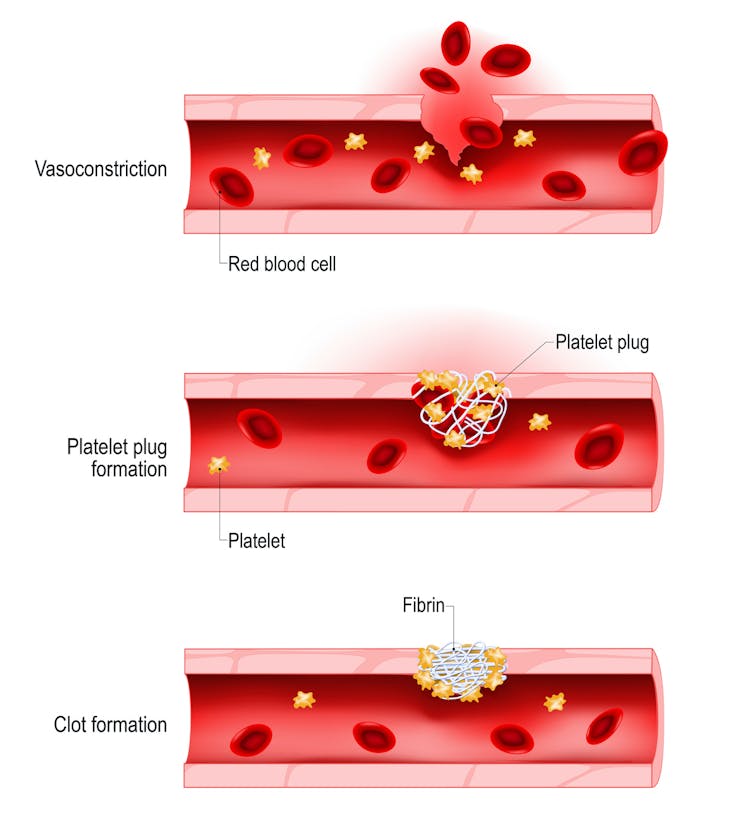

The skin forms a protective layer over our bodies. When that layer is damaged, the blood vessels immediately underneath it are torn, allowing blood to leak out.

A small cut tears just the small vessels near the skin, and only a tiny amount of blood drips out. A deep cut might tear larger vessels and cause more bleeding. When we bang an arm or a leg, tearing the smaller vessels without damaging our skin, blood collects under the unbroken skin to form a bruise.

Because the heart is still pumping blood throughout the body, more blood will continue to leak out until the damage is patched up. To stop the leaking, a torn blood vessel releases chemicals that activate proteins that clump together and form a plug to fill the hole. This seals up the blood vessel and prevents more blood from getting out. You’ve seen the results of this on your skin before: the scab that forms on top of a scrape or cut.

Applying pressure to a wound helps stop bleeding because it pushes the walls of the vessel together to slow the flow of blood. This helps form a clot to plug the tear, starting the healing process.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Mikkael A. Sekeres does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.