Deep in the Congo Basin, having traveled 100 kilometers upriver to the Nki National Park in Cameroon, William Gibbons heard a strange sound: a guttural bellow cutting through the swamp’s silence.

Gibbons was convinced this was no ordinary creature’s call. And indeed, this was no ordinary zoological expedition. It was an expedition to find something barely anyone else in the world believes exists.

Gibbons is a cryptozoologist — a person who pursues beasts thought to be mythological by most, including the scientific community. The most famous cryptid is probably Big Foot, but cryptozoologists also seek out other legendary creatures like the Loch Ness Monster or chupacabras. Gibbons and a small number of other cryptozoologists share another belief that makes their searches even more remarkable: Young Earth Creationism.

Young Earth Creationists are Christians who believe in a literal interpretation of the Bible’s six-day creation story. They believe the world is around 6,000 years old and that humans and dinosaurs once occupied the Earth at the same time.

The quest to prove this reading of the Bible is right is no idle stroll in Jurrasic Park.

For Gibbons and other Young Earth Creationist cryptozoologists, finding a flesh-and-blood, living, breathing dinosaur would not only be a scientific triumph but, they hope, could bury Darwin’s theory of evolution and prove their beliefs right. (Gibbons did not return multiple requests for an interview but has written extensively about his expeditions — these texts help form the basis of this story.)

Imagine dragons

Before Gibbons could find the source of that inscrutable bellow in the Congo Basin in 2013, his search was cut short by a fellow explorer in his crew falling seriously ill. As a result, they aborted the crowd-funded investigation to get their compatriot the urgent medical attention they needed. The creature was never found.

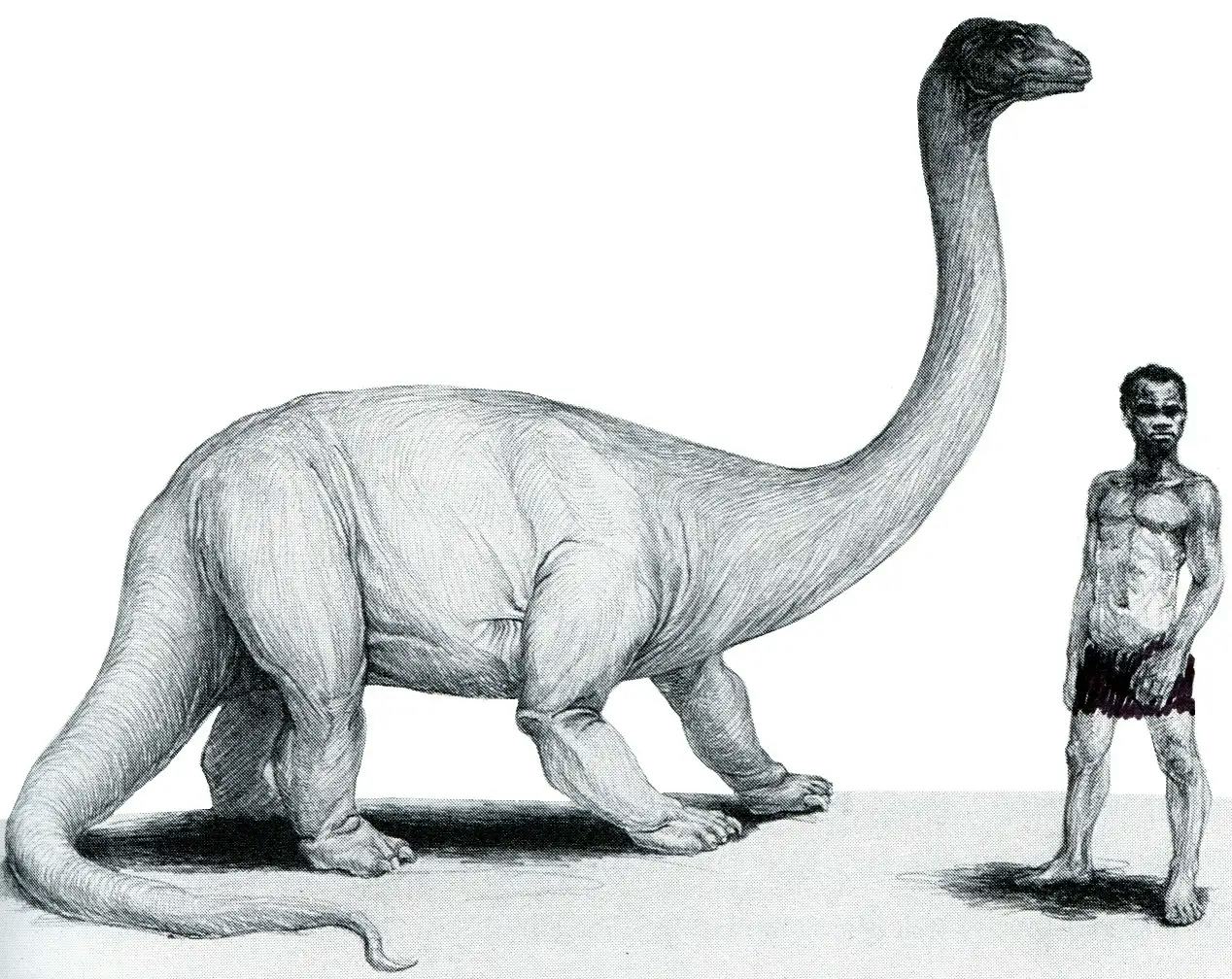

Unlike Scotland’s Loch Ness Monster, which some people believe to be a plesiosaur, Gibbons was looking for the fabled Mokele-Mbembe, a sauropod-like creature reported to have gray skin and be about the same size as an elephant. In Lingala, the language of the region’s nomadic Aka people, Mokele-Mbembe means the “one who stops the flow of rivers.” Whispers of its existence have circulated in Benin, Cameroon, and what’s now the Democratic Republic of Congo for hundreds of years. In 1776, French missionary Abbé Lievain Bonaventure recorded a three-foot-wide claw mark by a riverbank. Since then, there have been at least 50 western expeditions to track down the elusive beast.

“We... have a dangerous crisis in scientific authority and literacy.”

There’s no solid evidence Mokele-Mbembe exists, but eyewitness reports are plentiful. Local accounts range from metaphysical in nature (some claim it is a ghost) to the mysterious. Others argue the creature prowls the Congo Basin — mostly the Lake Tele region, in the Republic of the Congo. In 1992, a Japanese film crew searched for the creature and even gathered aerial shots of a disturbance at Lake Tele, but skeptics claimed it was probably people in a canoe.

Another explanation is that it’s a legend spun out of the true existence of the black rhinoceros. Hundreds of years ago, these large herbivores roamed the same region Mokele-Mbembe is supposed to have. Now, they are almost extinct.

Darren Naish, a former paleontologist at the University of Southampton and the author of Hunting Monsters, tells Inverse that despite eyewitness accounts and a supposed recorded bellow there is no physical evidence supporting the existence of sauropods in the modern era.

“Sightings are vague and could just as well represent observations of the big turtles and snakes cryptozoologists say are present in the same region,” he says.

Naish adds that a bellow “can’t be linked to sauropods” and that an “alleged track which appears on various cryptozoological websites doesn’t look like a real footprint — it certainly doesn’t look like a sauropod footprint.”

And yet, Gibbons has been on four expeditions in search of Mokele-Mbembe — not so much to find the monster as to disprove evolution. As he writes in the blurb of his 2006 book, Missionaries and Monsters:

“Perhaps the most exciting prospect for the world of creation science is the possibility that dinosaurs may still be living in the remote jungles of the world,” he writes. “Evolution… would be hard pressed to accommodate a living dinosaur.”

The evolution of Cryptozoology

Gibbons is not alone in his religiously inspired dinosaur hunting. A missionary named Eugene Thomas reported a Mokele-Mbembe killing in 1959. (Thomas passed away in 2005). Then there’s full-time Young Earth Creationist cryptozoologist Jonathan Whitcomb, who has investigated the possibility of a dinosaur called ‘Ropen’ living on Umboi Island, New Guinea. (Whitcomb did not return a request for comment for this story.)

There’s Kent Hovind, an American preacher who co-authored Claws, Jaws, and Dinosaurs with Gibbons. Hovind also runs Creation Science Evangelism Ministries (an education company) and an adventure park called Dinosaur Adventure Land that hosts “boot camp” events designed to “combat the lies of evolution and defend the truth of creation.” (Hovind spent eight years in jail for tax fraud, attempted to sue the federal government for half a billion dollars, and was arrested recently on domestic assault charges.)

Geologist and author Sharon A. Hill, who previously ran a skeptical blog and newsletter charting the paranormal, tells Inverse that her interest in dinosaurs led her to notice that a minority of people, like William Gibbons, repeatedly talk about living dinosaurs — and indicate they are experts on the subject.

Their attempts to capitalize on others’ skepticism is emblematic of a wider problem with how people view science, she says.

“We know more about the Moon than we do about life in the oceans.”

“We already have a dangerous crisis in scientific authority and literacy where supported theories and reason are discarded in favor of ideas that people prefer for ideological reasons,” Hill says. “The pandemic death toll and climate crisis are examples of where that path can lead us.”

“Young Earth Creationists don’t like orthodox science because it goes against what the Bible says in most cases. Their main purpose is to blow up science as a way of knowing, and they want to go back to the Bible as a way of knowing instead.”

Not all the explorers who search for Big Foot and other mythological creatures are out to disprove Darwin. Some pursue cryptozoology as a science. Some are after Mokele-Mbembe, too.

In the 1980s, University of Chicago biologist Roy Mackal and International Society for Cryptozoology founder Richard Greenwell searched for Mokele-Mbembe. They failed to turn up first-hand evidence but reported hearing anecdotal accounts. Others have set out to find the elusive creature, like cryptid researcher Adam Davies — but following expeditions in the 2000s, he too failed to produce evidence. There is even a 2020 documentary, The Explorer, about a French quest to find the creature — also a failure.

Rory Nugent, a cryptozoologist explorer and author of Drums Along The Congo, searched for Mokele-Mbembe at Congo’s Lake Tele in 1986. While he didn’t find conclusive evidence of the creature, he considers the trip a success as he was “hoping to lend credence to the idea of dinosaurs, and any search to find one’s dreams — to reify the experience of hunting for a lost piece of the distant past.”

However, Nugent tells Inverse that he finds Young Earth Creationism dubious at best.

“Young Earth Creationists? The very idea of such a living creature is boggling to me, and more far-fetched than that of Mokele-Mbembe itself,” he says.

While the cryptozoologist says his expeditions were the “perfect fit for his desire to document the obscure,” he considers his efforts very different from those of more religious cryptozoologists.

“Frankly, I believe in science and evolutionary theory, and consider Young Earth Creationists as massively misinformed and misguided,” Nugent says.

Missing link still missing

While it may seem humans have discovered all there is to discover, swathes of our biome are still being cataloged.

“There’s plenty ‘out there’ to be discovered,” Nugent says. “All sorts of insects and flora — it’s not so much that things are hiding, but more we don’t know where to look.”

“Cripes, we know more about the Moon than we do about life in the oceans,” he adds.

Multiple creatures once considered mythical beasts have made the leap from the realm of the cryptozoological to the plain old zoological. Take the Komodo dragon, thought by the European zoological community to be a legend until one was shot and killed in 1910. Or the okapi, which, although occasionally glimpsed by European explorers in central Africa, was not officially described until 1901 — it is on the logo for the International Society of Cryptozoology.

Then, in 2005, another discovery sent shockwaves through the scientific world — and had the unintended consequence of injecting Young Earth Creationists with a newfound sense of confidence. They felt on the cusp of the discovery of their dreams.

“By some estimates, there are 11,000 to 18,000 species of dinosaurs alive today.”

Molecular paleontologist Mary Schweitzer discovered what appeared to be remnants of blood vessels and fragments of blood-cell walls inside a largely intact T-Rex femur. Her discovery seemed to fly in the face of scientific understanding: How could these soft-tissue structures survive for millennia?

As soon as the findings were published, a torrent of creation-science articles and blog posts followed. Authors believed there was no way these biological materials could have survived so long. Rather, they must have been far younger than conventional science had thought.

It was not the “gotcha moment” that Young Earth Creationists had hoped for. Instead, Schweitzer proposed that a combination of the iron content in the dinosaur’s blood and the environment it was fossilized in may have helped preserve these soft-tissue fragments from the Cretaceous period. But the discovery still spurred Young Earth Creationist cryptozoologists to continue looking for living dinosaurs.

The entire incident, however, reveals a different problem with these cryptozoologists’ beliefs, however: A living, or recently deceased, dinosaur does not contradict evolution.

“There is a belief among creationists that the finding of a live sauropod or pterosaur would kill the theory of evolution by natural selection stone dead,” Naish says.

“I think this shows they don’t know what the theory of evolution by natural selection actually is, and that they haven’t done their homework on our understanding of animal diversity and evolutionary history.”

A living, or recently deceased, dinosaur does not contradict evolution.

Even if a sauropod was found alive somewhere, this would hardly disprove evolution, Evan Saitta, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago, tells Inverse.

“While it certainly would be surprising to find a living dinosaur, other than birds, such a discovery would not be inconsistent with evolutionary theory,” he says.

“Some modern organisms show relatively little anatomical change from their fossil relatives and are described as ‘living fossils.’”

“It’s not uncommon for gaps to exist in the fossil record of a particular evolutionary lineage — known as the ‘ghost lineage.’ In fact, amazing discoveries have already been made of presumably extinct species being found alive, much like those that the cryptozoologists seek,” he adds.

The irony is, Saitta adds, that birds are the direct descendants of small, feathered, ‘raptor’ dinosaurs. By modern naming conventions of biology, they are “by definition” dinosaurs, he says.

“This means that, by some estimates, there are 11,000 to 18,000 species of dinosaurs alive today,” Saitta says.

Jurassic larks

Finding a Mokele-Mbembe probably wouldn’t win former Young Earth Creationist, Reverend Dan Banks, vicar of St. Lawrence’s Church in Chobham, England, back into the Young Earth fold.

Banks tells Inverse that he sees cryptozoology as being more on the “conspiracy side of things,” and that he has “no interest in theories that are just not true.”

When he first became interested in a more literal interpretation of the Bible’s creation story, he found the struggle to square his religious beliefs with people and dinosaurs living together just a few thousand years ago a test of his faith.

“They’re not muddying the waters of science because they’re not doing science.”

“Not only did I have to persuade people of God’s existence and what Jesus had done for them, but I now had to throw images of triceratops with riding saddles into the mix too,” Banks writes in a blog post. He previously wrote for Biologos, a Christian group whose members believe in evolution.

Commenting on the cryptozoological efforts of Gibbons and his ilk, former Young Earth Creationist Luke Barnes, author of The Cosmic Revolutionary's Handbook, and an astrophysics lecturer at Western Sydney University in Australia, isn’t optimistic about their chances of success.

"I’m an astrophysicist. I have no idea, but I don’t hold much hope,” Barnes tells Inverse.

While cryptozoologists, wanna-be explorers, and film crews remain enamored with the potential thrill of discovering a creature like Mokele-Mbembe, Young-Earth groups continue to fund their own dinosaur-hunting expeditions, however fruitless they may be.

Young Earth Creationists’ cryptozoological expeditions “tell us a lot about belief systems in creationism,” says Naish, “but it isn’t presenting anything useful in a scientific sense.”

“The people doing these trips aren’t getting publishable results of any sort, and they seem just to potter around in the jungle, visit a few locations, and talk to the same groups of Congolese people. They’re not doing anything that’s of scientific interest or value, in other words, they’re not muddying the waters of science because they’re not doing science.”

For fans of prehistoric creatures who would love nothing more than confirmation of a living pterosaur or two, unless the Young Earth Creationists are able to offer more than indistinct bellows and eyewitness reports.

Until then, the Mokele-Mbembe will have to keep inhabiting the world of folklore.