The announcement by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to suspend fishing for Atlantic mackerel and spring herring in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence made waves as the fishing season opened.

This decision will have repercussions on the fishing industry at several levels since these species are fished not only for commercial purposes, but are also used as bait in the lobster, snow crab and Atlantic halibut fisheries. Given the precarious state of the adult part of these populations that can be exploited, also called stocks, closing the fishery is the right decision.

As researchers in fisheries ecology, we are interested in the dynamics of commercially exploited fish stocks. Here we explain the causes that led to the suspension of the mackerel and spring herring fishery in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence, as well as its implications for the fishing industry.

High adult mortality

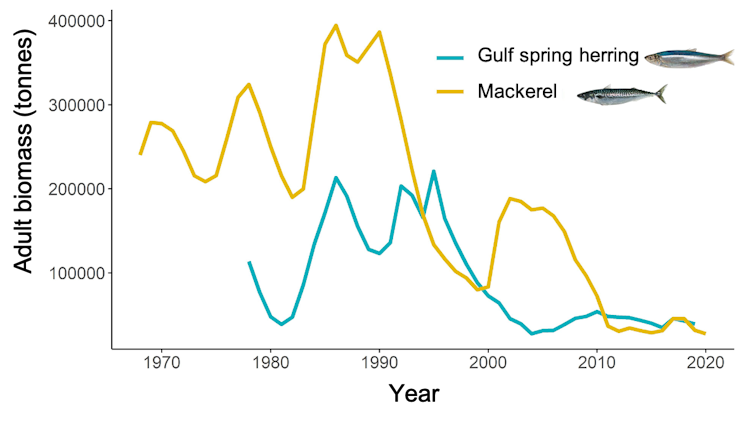

The latest stock assessment of Atlantic mackerel and spring herring in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence revealed high mortality rates among adult fish. Despite large reductions in commercial catches over the past 20 years, with quotas dropping to 4,000 tonnes from 75,000 tonnes for mackerel, and to 500 tonnes from 16,500 tonnes for spring herring, fishing mortality remained too high to promote stock growth, particularly for mackerel.

In addition to high fishing pressure, the natural mortality of fish by predation also increased rapidly, a phenomenon that is well-detailed in the herring of the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The grey seal, now 16 times more abundant than in the 1960s, is the main predator of herring.

Northern gannet populations on Bonaventure Island and Rocher aux Oiseaux (Bird Rock), also major consumers of herring and mackerel, are also at high levels.

Bluefin tuna is another top predator responsible for the high mortality of adult herring. Its abundance has rapidly increased in Gulf waters over the past decade.

Unfavourable environmental conditions

The current record lows of mackerel and spring herring can also be explained by a decline in the recruitment of these stocks.

Recruitment is the arrival of a new annual cohort to the adult stock. It has remained relatively low for herring since the 2000s, and for mackerel since the 2010s. This reduction in recruitment strength is most likely linked to environmental conditions that have become unfavourable for the larvae. Indeed, during the first weeks of life, when young fish are only a few millimetres long and are at risk of high mortality, their survival depends directly on the success of feeding on their main prey, microscopic crustaceans called zooplankton.

However, the rapid warming of the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence over the past two decades has altered the composition, distribution and developmental span of zooplankton organisms. This has led to a spatial and temporal shift between the emergence of mackerel and spring herring larvae, and the production of their preferred prey. This discrepancy weakened larval survival rate and caused recruitment failure, preventing the recovery of fish stocks.

Stock recovery will depend, in part, on the return to conditions that support larval survival and recruitment. Unfortunately, short-term climate projections do not allow us to foresee a return to colder years, which favour larvae survival.

Bait shortage expected

The impact of the spring herring and mackerel fishery closures extends beyond the commercial fishery of these two stocks. These species are the main bait in lobster and snow crab traps, and on hooks targeting Atlantic halibut and bluefin tuna.

These fisheries, among the most lucrative in the Gulf, are enjoying good times, having brought in more than $1.3 billion to Québec and Atlantic fishers in 2020.

This exacerbates the already high demand for bait. The anticipated additional costs related to the supply of bait may accentuate the rapid increase in prices for the most prized resources in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

What are the options?

The ultimate solution to the current crisis is to continue the strict management measures for the mackerel and herring stocks affected by the suspension of fishing, to preserve a sufficient number of spawners while waiting for environmental conditions conducive to their recovery. However, as these species only reach the minimum capture size at the age of three to four years, we cannot expect any short-term effect from management measures. We must be patient.

In the near term, fishers in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence will have to compensate for the bait shortage by sourcing mackerel from abroad. In Europe, for example, the stock is healthier. The direct and environmental costs of this transport do not make it an ideal long-term solution. The fall herring fishery, which remains open, may also allow fishermen to stock up later in the season.

There is an innovative solution under consideration, however. Alternative baits could be developed to completely replace herring and mackerel in shellfish traps.

Research teams are currently working on developing an effective recipe for making such baits using marine byproducts — materials derived from seafood processing that can be used for purposes other than human consumption.

The manufacture of alternative baits from species such as redfish, whose large-scale fishing should soon resume in the Gulf of St. Lawrence following the rapid increase in its numbers, is something well worth considering.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.