Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why can’t it always be summer? – Amanda, age 5, Chile

With its long days just itching to be spent by water doing nothing, summer really can be an enchanting season. As Jenny Han wrote in the young adult novel “The Summer I Turned Pretty”: “Everything good, everything magical happens between the months of June and August.”

But all good things must come to an end, and summer cannot last forever. There’s both a simple reason and a more complicated one. The simple reason is that it can’t always be summer because the Earth is tilted. The more complicated answer requires some geometry.

I’m a professor of geography and the environment who has studied seasonal changes on the landscape. Here’s what seasons have to do with our planet’s position as it moves through the solar system.

Closeness to the Sun doesn’t explain seasons

First, you need to know that the Earth is a sphere – technically, an oblate spheroid. That means Earth has a round shape a little wider than it is tall.

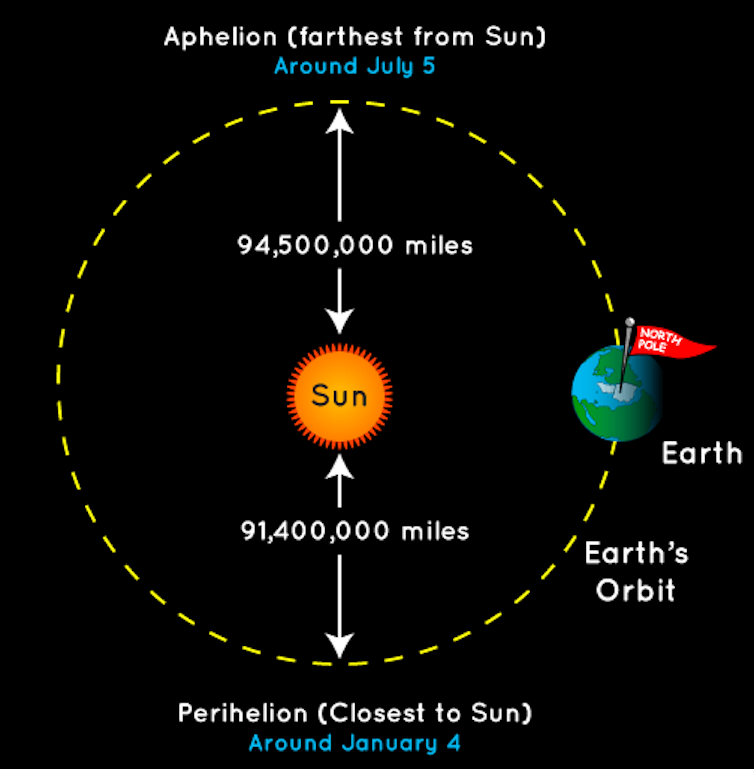

Every year, Earth travels in its orbit to make one revolution around the Sun. The Earth’s orbit is an ellipse, which is more like an oval than a circle. So there are times when Earth is closer to the Sun and times when it’s farther away.

A lot of people assume this distance is why we have seasons. But these people would be wrong. In the United States, the Earth is 3 million miles closer to the Sun during winter than in the summer.

Spinning like a top

Now picture an imaginary line across Earth, right in the middle, at 0° latitude. This line is called the equator. If you drew it on a globe, the equator would pass through countries including Brazil, Kenya, Indonesia and Ecuador.

Everything north of the equator, including the United States, is considered the Northern Hemisphere, and everything south of the equator is the Southern Hemisphere.

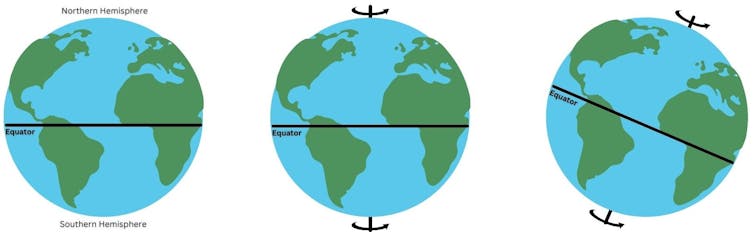

Now think of the Earth’s axis as another imaginary line that runs vertically through the middle of the Earth, going from the North Pole to the South Pole.

As it orbits, or revolves, around the Sun, the Earth also rotates. That means it spins on its axis, like a top. The Earth takes one full year to revolve around the Sun and takes 24 hours, or one day, to do one full rotation on its axis.

This axis is why we have day and night; during the day, we’re facing the Sun, and at night, we’re facing away.

But the Earth’s axis does not go directly up and down. Instead, its axis is always tilted at 23.5 degrees in the exact same direction, toward the North Star.

The Earth’s axis is tilted due to a giant object – perhaps an ancient planet – smashing into it billions of years ago. And it’s this tilt that causes seasons.

It’s all about the tilt

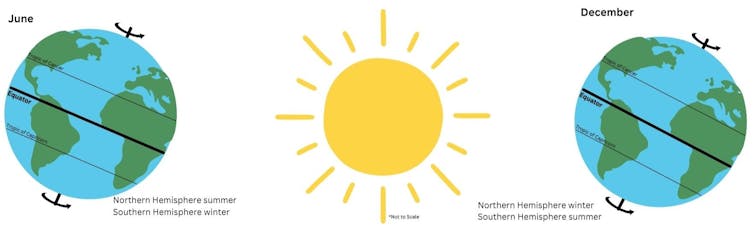

So that means in June, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun. That tilt means more sunlight, more solar energy, longer days – all the things that make summer, well, summer.

At the same time, the Southern Hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun. So countries such as Australia, Chile and Argentina are experiencing winter then.

To say it another way: As the Earth moves around the Sun throughout the year, the parts of the Earth getting the most sunlight are always changing.

Fast-forward to December, and Earth is on the exact opposite side of its orbit as where it was in June. It’s the Southern Hemisphere’s turn to be tilted toward the Sun, which means its summer happens in December, January and February.

If Earth were not tilted at all, there would be no seasons. If it were tilted more than it is, there would be even more extreme seasons and drastic swings in temperature. Summers would be hotter and winters would be colder.

Defining summer

Talk to a meteorologist, climate scientist or author Jenny Han, and they’ll tell you that for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, summer is June, July and August, the warmest months of the year.

But there’s another way to define summer. Talk to astronomers, and they’ll tell you the first day of summer is the summer solstice – the day of the year with the longest amount of daylight and shortest amount of darkness.

The summer solstice occurs every year sometime between June 20 and June 22. And every day after, until the winter solstice in December, the Northern Hemisphere receives a little less daylight.

Summer officially ends on the autumnal equinox, the fall day when everywhere on Earth has an equal amount of daylight and night. The autumnal equinox happens every year on either September 22 or 23.

But whether you view summer like Jenny Han or like an astronomer, one thing is certain: Either way, summer must come to an end. But the season and the magic it brings with it will be back before you know it.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Stephanie Spera receives research funding from NASA.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.