While thermometers have been well into the red across the northern hemisphere, people are panicking about the cost of energy bills once winter starts to bite. According to the latest forecasts in the UK, the minimum price cap for households’ electricity and heating costs is set to more than double over the winter.

Other commentators have suggested that these fears are being overdone, and that the weakening global economy and moves to fix energy supply issues will bring down prices. We asked energy expert Adi Imsirovic for his view on where things are heading.

The price of oil has been falling recently – why?

Energy prices don’t like two things: recessions and higher interest rates. At present, the prospects for the global economy are getting gloomier and interest rates are going up.

When interest rates are low, speculators can borrow money cheaply to make bets on energy prices going up, but this becomes less attractive as rates rise. Commodities also always have the disadvantage that you are not paid to hold them, unlike dividends on shares or interest payments on bonds.

The yields on these other assets tend to go up when interest rates rise, which makes commodities relatively less attractive to investors. Even compared to another commodity like gold, oil is much more expensive to store, so you are also paying a lot to hold the investment.

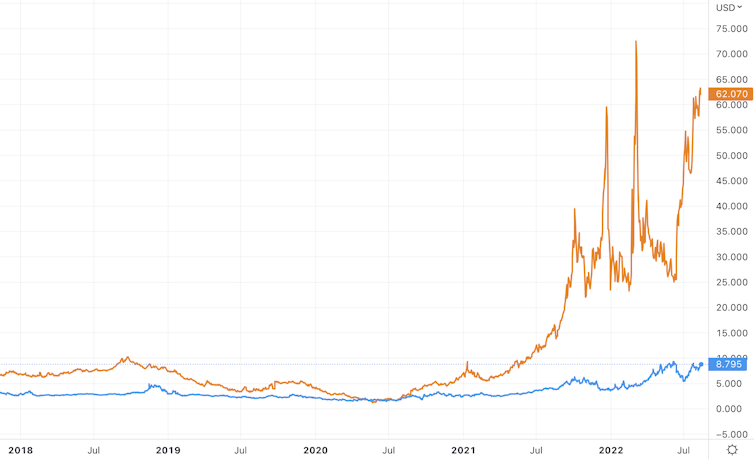

Brent crude (US$/barrel)

Why has natural gas held up better than oil?

Because oil can easily be sold elsewhere. If Europe doesn’t buy Russian oil, it can instead be shipped to Asia. It might be a different story when the European restrictions on insuring ships carrying Russian exports come into force at the end of the year, but that’s for the future.

On the other hand, when Russia decides not to sell its gas to Bulgaria or Poland or Finland, the gas broadly either stays in the ground or gets burned in Russia. In effect, you are losing the supply to the world market, whereas the overall drop in oil exports from Russia during the war has been small.

Europe also doesn’t have many alternatives to Russian gas. It has to buy LNG (liquefied natural gas) from Asia on the spot market, bidding up the price shipment by shipment.

This is very visible to everyone else in the market and therefore increases the sense of panic. It’s a very similar situation to oil in 1979, during the Iran hostage crisis, when majors like BP had too little to fulfil supply contracts and had to go to the spot market and bid for barrels.

What will determine what happens next to gas prices?

Several variables, the first of which is weather. If the winter is mild, then given current European stock levels we might be fine. If it’s very cold, that’s a different situation.

The war in Ukraine will be crucial. Were there to be some kind of peace agreement, gas prices could change overnight. But I doubt that will happen when the stakes are so high. If Putin loses the war, he’s finished.

Then there is China, which is a very big consumer of gas. Europe has been extremely fortunate that China has been struggling with COVID and subprime property difficulties. The most recent news was very poor, suggesting it is heading for recession.

As a result, Chinese demand for LNG across 2022 looks set to fall by at least 10% from the 2021 level. If Chinese demand bounces back and it starts buying more LNG again, prices still have the potential to go up a lot.

As for the US, its LNG production has been reduced by the temporary closure of a major terminal in Texas following an explosion. The latest news suggests it will be back onstream by October, making more gas available to Europe.

But don’t assume that demand in the US stays as strong as it has been. It’s highly unlikely that the US will avoid a recession.

Even if inflation is on a downward trajectory, you still probably need four or five large increases in benchmark interest rates to get to positive real rates [meaning a positive rate after you subtract the rate of inflation], which many would argue is necessary to get inflation under control. Maybe benchmark rates have to double to over 5%. There’s no way the economy is going to stand still while you are doing that.

So some potential pulls in both directions. What’s your best guess about where the price goes?

Whereas oil is very sensitive to economic growth, this is less true of gas because a large amount of it is used for domestic heating and power (the UK is particularly dependent in these respects). Yes, demand for gas falls during a recession but it’s difficult to substitute on the domestic front.

So I come back to Putin. For him the key was to avoid an oil embargo, but that will happen one way or the other by early 2023. That makes it all the more important for him to continue to use gas as a weapon. We’ve seen how he has cut off countries to the east of Europe, and played games over Germany’s supply. We’re very likely to see more of this, and uncertainty makes markets more volatile.

As long as Putin stays in power, prices are likely to stay elevated simply because he will make sure that they do. I think we’re going to continue to see the market trading above prices equivalent to about US$60 (£50) per British thermal unit, which is crazy when you realise that the equivalent US price is US$9.

European vs US gas prices

Are there any reasons for hope besides weather?

We have seen the problem relatively early, so that maximises our chances of addressing it. I do worry when I see Labour and the Lib Dems in the UK, and politicians in places like Italy and Spain, calling for price freezes. That will just encourage more fossil fuel use at a time when we need to be bringing it down. Much better to help poorer people with handouts.

Where do you see oil heading?

All other things being equal, I think it stays around US$100 per barrel plus or minus US$10. I predicted prices would go higher in the early stages of the Ukraine war, which they did, but inflation and the economic outlook have since made a big difference. It’s now more obvious that the growth after the COVID lockdowns was thanks to the stimulus packages, and as I say, benchmark interest rates have to rise higher.

Over the longer term, there are those like Goldman Sachs who say we’re in the early stages of a super-cycle in oil which will see prices go much higher, due to the COVID stimulus packages and a long-term lack of investment in new oil production. But I do not quite agree.

I come at it from the other direction: by 2030 we need to reduce oil production from about 100 million to 70 million barrels per day to be on track to meet net zero commitments. In view of all the policies being put in place to make that happen, I think a decline in demand is inevitable.

Adi Imsirovic does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.