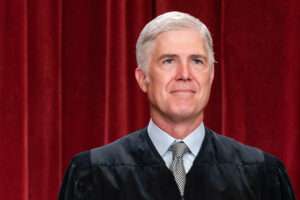

In a recent post, co-blogger Josh Blackman notes that Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch has never ruled against Indian tribes or their members since getting on the Court in 2017. Because of this record, Josh goes on to write in a follow-up post, he is "skeptical of any Gorsuch opinion that rules for an Indian tribe or member." The implication is that Gorsuch is biased in cases involving Indian interests and rights. His consistent record of ruling in favor of Indian interests proves it.

But does it? A Supreme Court justice who always or almost always rules in favor of one type of litigant could well have unbiased reasons for doing so. Consider a Supreme Court justice 100 years ago who virtually always ruled in favor of black litigants in civil liberties and antidiscrimination cases. Perhaps such a justice acted as he did because he had a bias in favor of blacks (or against whites). But the more likely explanation is that the justice thought existing precedent on these issues was itself biased against black rights (which was in fact the case!).

Supreme Court cases are not a random sample of the possible universe of legal issues. Most are chosen by the justice because they involve matters where existing precedent is unclear on the issue in question or does not cover it, or (less often) attempts to reverse or limit current precedent. If existing precedent is heavily biased towards one side, it makes sense for a justice who objects to that bias to always (or almost always) rule for the other.

In Gorsuch's view, what was true of precedent on black civil rights a century ago is true of Indian issues today. He believes existing precedent shortchanges Indian tribes and other Indian interests on a wide range of fronts. And, as in the case of blacks back then, the bias is the outgrowth of a long history of discrimination and oppression. Gorsuch sets out much of that history in his lengthy concurring opinion in Haaland v. Brackeen.

I think Gorsuch is right about the horrific history, but perhaps wrong about some of the implications for legal doctrine. Among other things, I am skeptical that Congress's power over Indian issues should be as broad as Gorsuch suggests, and I am particularly opposed to provisions of the Indian Child Welfare Act that authorize extensive racial and ethnic discrimination in making adoption decisions respecting children with Indian ancestry. On that latter point, I agree with co-blogger David Bernstein. But the issue here is not whether Gorsuch is right about these issues, but whether his votes in Indian cases are the result of bias.

Although Gorsuch may be wrong, it seems clear he has a principled stance on how existing doctrine gives short shrift to Indian tribes and other Indian interests, and seeks to correct that bias. It's not a matter of special favoritism for Indians, as such.

In the same way, I think property rights claims deserved to prevail in almost every Takings Clause case involving property rights in land, or personal property, that reached the Supreme Court over the last several decades. Do I have a special bias in favor of landowners' interests? Maybe. But my position on this is that it is existing Supreme Court precedent that is biased against property rights in various ways, for historical reasons arising from the Progressive and New Deal eras. I set out some of the relevant history in my book The Grasping Hand. While things have improved somewhat over time, it is still true that property rights often get weaker protection than most other constitutional rights, and takings cases that reach the Supreme Court are therefore still almost always ones the property owners deserve to win.

Could I be wrong about that? Sure. But if so, it's not because of a special bias in favor of landowners. To the contrary, much of my work emphasizes that the biggest victims of judicial neglect of property rights are often people who don't themselves own land, such as victims of exclusionary zoning and renters forced from their homes due to abusive use of eminent domain.

Things are different if we focus on lower court judges, rather than Supreme Court justices. If a district court or circuit judge virtually always votes for Indians, blacks, whites, landowners, or some other identifiable social group's interest, that is much stronger (though not conclusive) evidence of bias. Or at least that's true if the judge has heard any significant number of cases involving members of those groups.

Lower court cases are a much less carefully selected sample than those that reach the Supreme Court. Many lower court cases involve highly dubious claims or "Hail Marys" that have little or no merit under any plausible legal theory.

There are a number of areas of constitutional law where serious arguments can be made that current precedent is unjustifiably biased in on direction. A justice who believes existing doctrine is flawed in that way may have good reason to act as Gorsuch does in Indian cases. At the very least, the justice's voting pattern cannot easily be dismissed as biased in favor of a particular group.

The post Why a Supreme Court Justice Who Always Votes for One Type of Litigant isn't Necessarily Biased appeared first on Reason.com.