Fifty one year-old Jin Xing is a pioneering artist.

She is an internationally acclaimed, award-winning contemporary dancer, founder and director of the Shanghai Jin Xing Dance Theatre – China’s first independent dance company – and a celebrated television host of several hit shows in mainland China, such Venus Hits Mars, The Jin Xing Show and Chinese Dating.

She is also the first public figure to undergo sex reassignment surgery (SRS) in China.

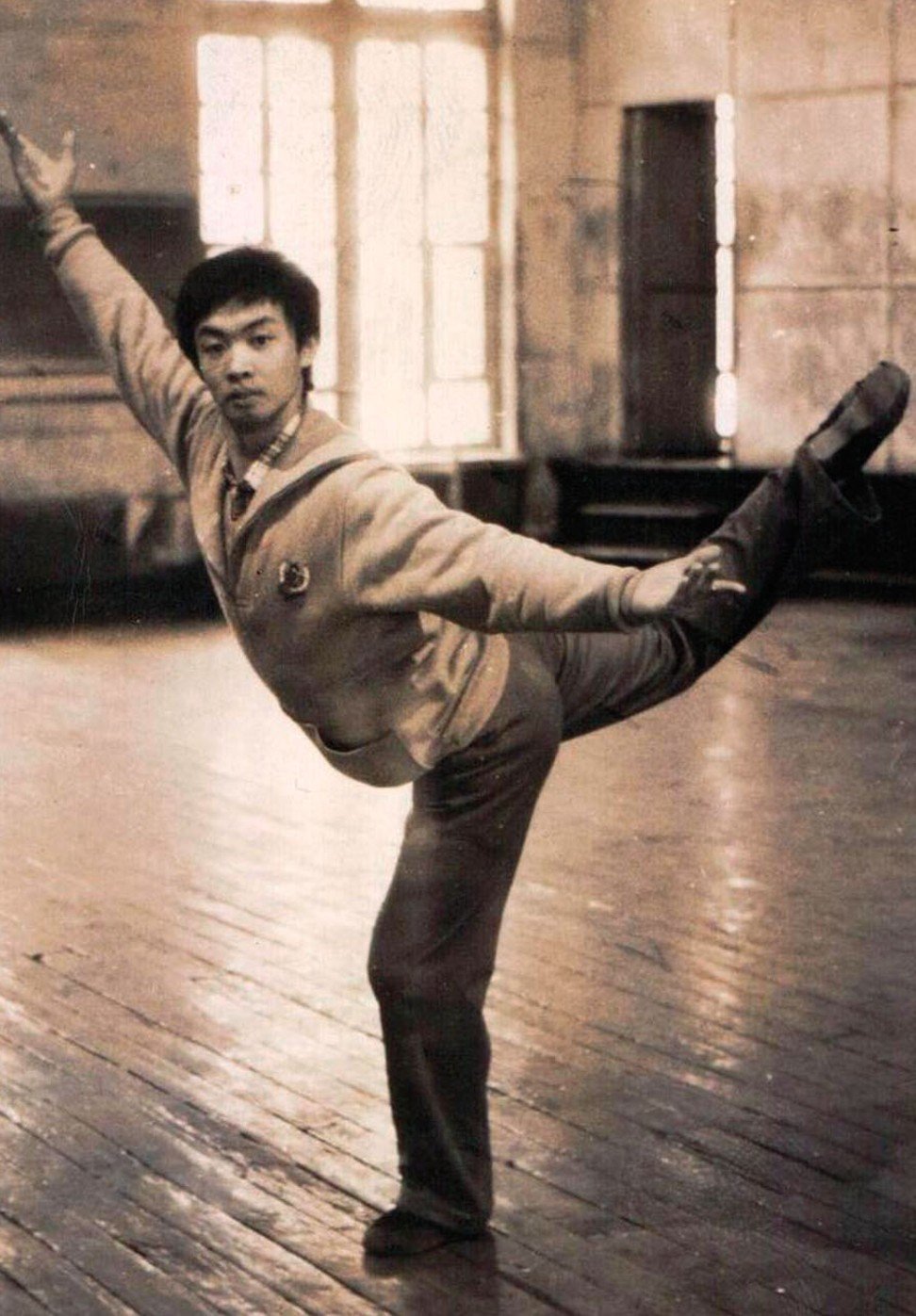

Born in 1967 in Shenyang, Jin has been passionate about dancing since her early childhood.

How Chinese actress Zhou Dongyu rose from rookie to starlet

Dance and the arts were seen as propaganda tools in China at the time and Jin’s gift was so apparent that by the age of nine, she was accepted into the People's Liberation Army to train in the dance troupe.

Jin graduated in 1984 and was granted the rank of colonel.

It was at this time, when she won her first national dance championship and was crowned the number one male dancer in the country, that she became aware of a dance scholarship in New York that was funded by a cultural exchange programme.

That allowed Jin to leave China, and a strict military regimen, and to consider her sexuality for the first time.

“Now I was free to discover myself. Maybe I'm gay? But I didn't think so,” she told Hollywood Reporter in 2016.

“Then I went to the gay bars, met a gay friend, but I said, ‘No, no, I'm not gay’.

“My sexuality is still like a female’s. That's when I discovered words – transsexual, transgender.

“I said, ‘OK, I belong to that small island’. Then I started researching.”

Torn by the feeling since she was young that her mind did not belong in her body, Jin used to fantasise that she could change her sex by being struck by lightning.

‘Modern Family’ star Sofia Vergara tops the list of highest-paid TV actresses

It was after her time in the United States that she decided to undergo SRS, although it was not until she was 28 that the transition finally happened.

“In China, to change gender, there is a requirement for SRS,” says Marc Rubinstein, co-founder’s of the Hong Kong Gay and Lesbian Attorneys Network.

“Under regulations issued in 2009, the prerequisites to being eligible for SRS include diagnosis of gender identity disorder by a psychiatrist and demonstration of an intention to change gender for at least five years.

“Hospitals may also require family consent even for young adults who have passed the age of 18.”

While Jin underwent such a revolutionary transition in 1995, the conditions to have access to SRS in China have not progressed much in the last two decades.

“[The requirement to complete SRS to change gender] is a relatively restrictive regime in regards to gender recognition, compared to global best practices [in] jurisdictions such as Argentina and Malta where a self declaration model has been adopted,” Rubenstein says.

Jin’s journey, though, was not an easy one.

Already a prominent figure in the art scene, Jin’s decision to undergo SRS became a national sensation.

Her transition was documented by the press and she became the first openly transgender person in China.

While all this attention could be misconstrued as acceptance, entertainers in Chinese culture have a long history of being an ostracised social class.

“Entertainers were historically treated differently in China,” says Arthur Tam, former film and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender editor at Time Out Hong Kong.

“They had social fluidity due to their access to different social classes because of what they do, but at the same time they’re not fully accepted; seen either as exotic or subordinate.”

To make things worse, a mishap during her 16-hour surgery left her leg paralysed, which could have ended the award-winning dancer’s career.

To Jin, dancing was not just what she did, it was her whole life.

“I wanted to jump to my death at that moment,” she says.

“Dancing is my life. How can I live without it?”

K-pop singer-actress Suzy Bae donates US$90,000 to sick children

And all of this happened in the full glare of the public eye.

Jin immediately began intense physiotherapy after her release from hospital.

Her determination and fighting spirit triumphed, though: she was able to make a full recovery and danced on stage in Beijing only a year later – as a woman.

“I've never cried onstage, but that time I cried, when I took the final bow,” she says.

“I was thinking, ‘Yes, I got back my [place on] stage and I've got back my leg’.”

Today, she has her own dance company and her achievements in art of dance are recognised by institutions around the world.

In 2012 Jin received the honour of “Literature and Arts Knight” from the French Ministry of Culture, while in 2014 she was granted an honorary doctoral degree in dance arts by the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, formerly the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama.

Yet these awards were just tip of the iceberg in terms of her growing appeal and profile.

Famous for her sharp tongue, candid personality and dancing talent, Jin was approached to host her own television talk show, The Jin Xing Show, in 2012.

Its success rocketed her to national fame, amassing more than 1 million viewers each weekend, and was considered a family show for mainstream audiences.

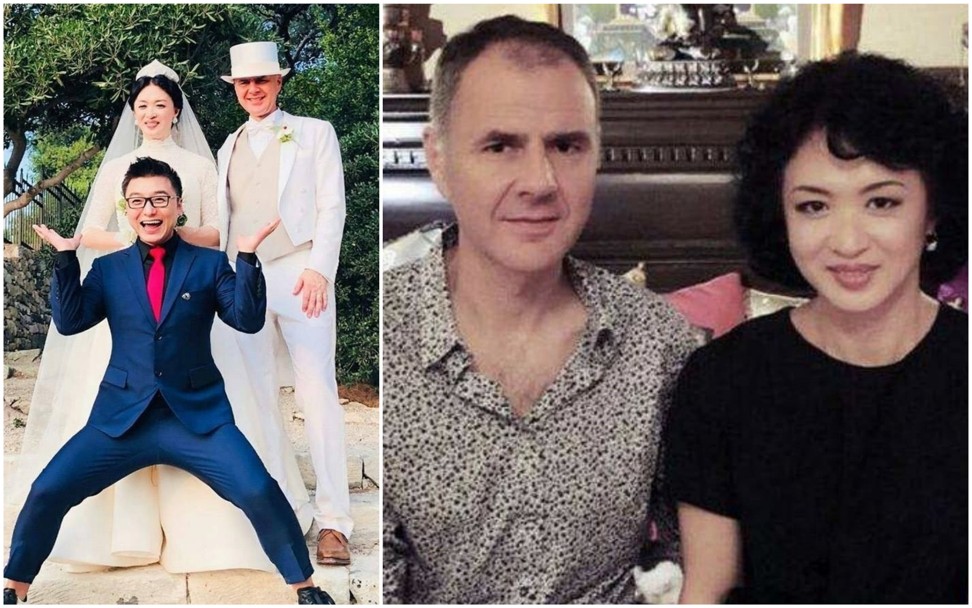

Jin is now the mother of the three adopted children named Leo, Vivian and Julian, and married her German husband Heinz-Gerd Oidtmann in 2005.

While her transition has been a great success story and she has successfully overcome the resulting problems, Jin’s story does not have a happy ending just yet.

A shadow is now looming over her career.

Han Ji-min goes from sweetheart to angry convict – and is loving it

Jin had enjoyed her high profile and success in China and had never been censored by the Chinese government or any other authority.

This was widely seen as tacit permission – until July 2017, when The Jin Xing Show was suddenly cancelled without any explanation.

Being openly gay or transgender is still risky and also widely considered as taboo subject in China.

A report funded by the United Nations Development Programme released in August found that there are still lots of policies and practices involving inequalities towards China’s transgender community.

While the show’s cancellation has been a blow to Jin personally and professionally, she knows that social progress takes time.

“When I did the gender reassignment surgery two decades ago, only 30 per cent of people sided with me,” Jin told the South China Morning Post.

“Nowadays, I think about 80 per cent of people recognise my choice.”

7 things you didn’t know about ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ actress Victoria Loke

In a global climate where transgender issues are being used as a scapegoat to advance political agendas, stories such as Jin’s and greater representation are needed more than ever.

“It’s important for individual stories to be told,” Rubinstein says.

“Stories have the ability to connect and, if Jin Xing had never transitioned and made her story public, nobody would be able to identify with her as someone they already knew and loved.”

Want more stories like this? Sign up here. Follow STYLE on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter