Laura Kuenssberg's move from the BBC to ITV again demonstrates the sensitivities around using social media – which is principally designed for individuals to communicate – for professional purposes.

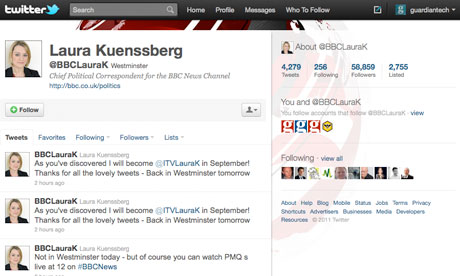

The BBC's chief political correspondent – at least until September when she leaves for ITV – Kuenssberg has built up a significant following of 58,800 on the account @BBCLauraK since she signed up in July 2009. That audience of followers will be some of the BBC's most engaged political news junkies, but also fans of her specifically, following her on Twitter for extra personality, colour and breaking news that they have come to associate with her style of reporting.

Rather than handing her old account login back to the BBC to start from scratch with a new ITV account, the sensible thing to do is to change the name of the account. The BBC's next chief political correspondent could hardly step in and take over the account anyway – that's not what Kuenssberg's followers signed up for, and that next reporter is likely to have their own account.

ITV confirmed that @ITVLauraK and @laurakitv have both been registered by the online team, though Kuenssberg does not have to use either. There is no fixed guideline on using ITV News branding in Twitter accounts; @tombradby doesn't, while Bill Neely does.

Setting up an account that blends professional and personal is a risky move. Though it may help for identification and promotion to use the BBC's name, for example, it implies some kind of ownership and control. Thanks to social media, there is a shift towards the autonomy of reporters that affords many benefits in engagement and interaction with readers. It's a move towards openness and individualism that, for relevant subject areas of reporting, helps break down the overly formal walls between readers and a news brand. While a reporter works for a specific brand, they will direct traffic and influence to their own news stories, and when they move on, they take that with them. That transfer works to and from organisations, and is far cleaner for the public and for the brand.

Where brands can now have dedicated pages on Facebook, which appears to fulfil the demands of brands more than the priorities of users, that principle doesn't translate so well to Twitter, which is designed for individuals to communicate. Bland "company line" messages don't work – what does work is a real conversation with a real, named, identifiable person who works for that brand.

The New York Times, much like the Guardian, has only very loose social media guidelines for reporters, preferring to allow them to explore and engage with readers in what is still a very new medium but one that is a powerful way of gathering tips, feedback and spreading influence. Reuters, on the other hand, instructs reporters not to break news via Twitter, preserving its exclusivity for traditional full news stories – but then Reuters is arguably less focused on "personality" journalism.

On the micro-management end of the scale, the Toronto Star's Twitter policy details how reporters must not discuss stories in development or "editorialise on topics they cover", which sounds rather like a blanket ban on anything outside tweeting a link to a story.