From the pioneers of the Golden Age of Alpinism and early exploration of the Himalayas to the conquest of Everest and the development of fast and light alpinism in the Greater Ranges, Britain has played a pivotal role in the history of mountaineering.

It’s an island that boasts only modest peaks when compared to the likes of those found in the Rockies or the Alps, but Blighty has produced a grand array of legendary characters, far too many to name here. We asked our mountaineering expert to reveal some of Britain's greatest ever mountaineers and their achievements.

Who are Britain’s greatest ever mountaineers?

Here is our selection of Britain’s greatest ever mountaineers, from the Victorian trailblazers to the modern-day pioneers quietly shunning the circus of 8,000-meter peaks to climb technical lines on previously unheard of 7,000-meter beauties. As ever, a definitive list is impossible and there are many greats who also deserve a place on the list but haven't made the cut. Special mention has to go to Dougal Haston, Joe Brown, Don Whillans, Hamish MacInnes, Al Rouse, Alex MacIntyre and Alan Hinkes, as well as to Adriana Brownlee who became the youngest woman to have climbed all fourteen 8,000 meter peaks in 2024. Perhaps we’ll need a part 2 somewhere down the line?

Treat the list as a celebration of great characters from across the different eras. Hopefully it will serve as inspiration for some adventures of your own.

Britain's greatest ever mountaineers

Edward Whymper: Figurehead of the Golden Age of Alpinism and leader of the fateful first ascent of the Matterhorn.

Lucy Walker: Trailblazing alpinist who achieved a number of first female ascents, including the Eiger and the Matterhorn.

George Mallory: Early Everest pioneer and the figure at the centre of mountaineering’s most famous mystery.

Sir Chris Bonington: Legendary figure who played a pivotal role, leading many expeditions during a golden age or British mountaineering.

Doug Scott: A true visionary who achieved first ascents of many great prizes in the Himalayas and beyond, applying an alpine ethos to the world’s biggest mountains.

Joe Tasker and Peter Boardman: Partners who took the fast and light approach to the Himalayas and ended up paying the ultimate price.

Alison Hargreaves: First person to climb all six alpine north faces in a single season and first British woman to climb Everest solo and without supplementary oxygen.

Martin Moran: First to climb all of Scotland’s Munros in a single winter, influential Scottish Winter climber and the first to achieve a continuous traverse of all the Alpine 4,000ers.

Mick Fowler and Paul Ramsden: Multi Piolet d’Or winning duo who specialize in highly technical, unclimbed 7,000-metre peaks.

Edward Whymper

Edward Whymper’s name will forever be synonymous with one of the world’s most iconic peaks: the Matterhorn. Born in 1840 in London, Whymper was one of the leading lights during the Golden Age of Alpinism, a period between 1854 and 1865 when many of the major peaks of the Alps were conquered for the first time, often by British alpinists alongside French and Swiss guides. After his time in the Alps, he’d go on to explore the world, with trips to Greenland, the Canadian Rockies and the Andes, making the first ascent of Chimborazo, the 6,263-meter volcano that’s interestingly the farthest point from the Earth’s centre.

Whymper first visited the Alps in 1860, tasked with producing drawings of the majestic scenery. The sight of Mont Pelvoux in the Dauphiné Alps must have inspired him as, in 1861, he was back to climb to the summit. Many expeditions in the Alps followed and Whymper was particularly prolific in 1864 and 1865. He returned to the Dauphiné Alps to claim the first ascent of the Barre des Écrins alongside fellow Brits Adolphus Warburton Moore and Horace Walker, as well as legendary guides Frenchman Michel Croz, and Swiss father-son duo Christian Almer Senior and Junior. Croz and Whymper were particularly formidable as a pair, claiming further important first ascents together in the Mont Blanc range. This included the first ascent of second highest point on the Grandes Jorasses, subsequently known as Pointe Whymper, alongside Christian Almer. Whymper also teamed up with Almer again to claim the first ascent of the iconic Aiguille Verte.

The Golden Age came to an end with a climb that would define Whymper’s legacy. In 1865, one great prize remained: the Matterhorn. Whymper had tried to climb it several times before, along with John Tyndall and Italian guide Jean-Antoine Carrel, and had become convinced that the Hörnli Ridge on the Swiss side was the key to unlocking the summit, despite its intimidating appearance. In July 1865, he tried to secure Carrel’s services for an attempt via the Hörnli Ridge, but Carrel pulled out at the last minute, lured to instead attempt the Lion Ridge on the Italian side by Felice Giordano.

Undeterred, Whymper assembled his team – Croz, Zermatt locals Peter Taugwalder and son, Lord Francis Douglas, Charles Hudson and Douglas Hadow – and on July 14, they successfully ascended the Hörnli Ridge. However, tragedy struck the roped party during the descent when the inexperienced Hadow slipped, dragging Croz, Douglas and Hudson off the ridge and to their deaths. In a twist of fate, the length of rope linked to Whymper and the Taugwalders snapped, saving their lives. It was an event that would haunt Whymper for the rest of his days.

Lucy Walker

Lucy Walker was the first woman of any nationality to climb extensively in the Alps, achieving a staggering list of female first ascents, including the Eiger and the Matterhorn. She was the older sister of Horace Walker, himself a legend of the Golden Age of Alpinism.

Born in what was then known as British North America (now Canada) in 1836, her family moved back to the UK and she grew up in Liverpool. She was introduced to the world of alpine climbing by her father Frank, an early member of the prestigious Alpine Club, then in its infancy. In the late 1850s and early 1860s she explored the Alps extensively, forming a strong climbing relationship with Swiss guide Melchoir Anderegg, who was a constant presence during her alpine career.

Between 1860 and 1873, she’d claim a string of female first ascents that included notable peaks like the Eiger, Weisshorn, Aiguille Verte and Taschhorn. Meanwhile, on 21st July 1864 – along with her father, brother Horace (fresh from his successful first ascent of the Barre des Écrins with Whymper et al), Anderegg and his cousin Jakob – she achieved the first ascent of any kind of the Balmhorn in the Bernese Alps.

However, her greatest prize was won on 21st July 1871 when she, in a party that included Anderegg and her father, beat rival American mountaineer Meta Brevoort to the summit of the Matterhorn, becoming the first woman in history to stand on the iconic summit.

Unsurprisingly, Walker had to overcome many social barriers to achieve her great feats. Victorian society dictated that a woman’s place was in the home, certainly not gallivanting about on alpine peaks. Walker had to be accompanied by a family member on all of her expeditions as being alone with an unrelated man would have been awfully unbecoming. She also had to wear a long flannel skirt for modesty, a far cry from the hiking pants and shorts of today!

Meet the expert

George Mallory

Just as Whymper will forever be associated with the Matterhorn, so too George Mallory will be ever associated with the world’s highest mountain: Everest. He is the figure at the centre of one of mountaineering’s greatest mysteries, when he and climbing partner Sandy Irvine were spotted ascending towards Everest’s summit on 8th June 2024 by fellow mountaineer Noel Odell. They disappeared into the clouds and were never seen alive again. No one knows for sure whether they made it to the top or not.

Introduced to Alps during his time at college, Mallory quickly developed a passion for the mountains. In the early 1900s, he developed his climbing skills on the relatively modest peaks of Eryri (Snowdonia), the fells of the Lake District, and the mountains of the Scottish Highlands . These adventures were punctuated by several expeditions to the Alps, where Mallory achieved a number of firsts, including new lines of the Aiguille du Midi and the Aiguille des Grands Charmoz on the Mont Blanc massif.

Following the First World War, the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club established the Mount Everest Committee with the intention of finding and achieving a route to the summit. Mallory was invited on the first expedition in 1921. Although reluctant at first – after all, Mallory had a wife and children to think of – he eventually accepted. He became enraptured by the idea of climbing Everest and the mountain’s pull would mean he’d return in 1922 and, fatefully, in 1924. In 1923, when asked by a reporter why he wanted to climb Everest, he uttered perhaps the most famous words in mountaineering history: “Because it’s there”.

After 75 years on the North Face of the world’s highest mountain, Mallory’s body was discovered by American mountaineer Conrad Anker in 1999. In October 2024, American mountaineer and filmmaker Jimmy Chin discovered Sandy Irvine’s boot. Despite these discoveries, conclusive evidence of whether or not Mallory and Irvine made it to the summit or not has yet to be found.

Sir Chris Bonington

Sir Chris Bonington is a heavyweight of British mountaineering who achieved an almost unrivalled record in the Greater Ranges and across the world during the 1960s and 70s. Along with the likes of Doug Scott, Dougal Haston, Don Whillans and Joe Brown, he was a leading figure during this golden age of mountain exploration.

Early achievements in the Alps included being part of the first British team to climb the Bonatti Pillar on the Dru in 1958; being part of the first British team climb the North Face of the Eiger, also in 1958; and in 1961, achieving the first ascent of the Central Pillar of Freney on Mont Blanc with Don Whillans, Ian Clough and Jan Dlugosz. His Himalayan exploits in the early 1960s were hugely impressive, achieving summits during the first ascents of Annapurna II in 1960 and Nuptse in 1961. He took his rock climbing prowess to Patagonia, claiming the first ascent of Chile’s staggering Central Tower of Paine alongside Whillans in 1963.

His skill and personality meant that he’d soon become expedition leader for many British forays into the big mountains. He was at the helm for the extremely ambitious 1970 British Annapurna South Face expedition, which successfully placed Whillans and Haston on the summit. It was the first ascent of an 8,000-meter peak to require big wall climbing techniques and its success was widely praised by the mountaineering community as Britain’s most important achievement since the conquest of Everest in 1953.

The mid 70s were particularly fruitful for Bonington. In 1974, he was part of the all-star line-up with Scott, Haston and Martin Boysen that claimed the first ascent of Changabang, a staggering peak in the Garwhal Himalayas. Then, in 1975, he led the British Everest Southwest Face expedition, which saw Haston, Scott, Peter Boardman and Pertemba Sherpa make it to the summit. The ascent of Pakistan’s Baintha Brakk with Scott in 1977 turned into an epic during the descent when Scott fractured both his legs and the team were forced to retreat through a storm. Both Scott and Bonington survived, though Bonington broke his ribs during the effort.

More successful climbs followed in the 1980s, with first ascents of Kongur Tagh in China and Shivling, a striking peak that’s been coined ‘the Matterhorn of the Garwhal Himalaya’. In 1996, he received a knighthood for services to mountaineering and, in 2015, he was honoured with the Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement Award, the second Brit to receive the accolade, after a certain Doug Scott…

Doug Scott

Born in Nottingham in 1941, Doug Scott holds the accolade of being the first English person to reach the summit of Everest. He and Scottish mountaineer Dougal Haston achieved the summit as part of the pioneering 1975 South West Face of Everest expedition and then were forced to bivouac on the South Summit after it’d become too dark to continue. This was the highest forced bivouac in history and propelled Scott and Haston to wider renown.

He was an early proponent of taking lightweight alpine approaches to the world’s big mountains and his list of achievements and first ascents is truly remarkable. His most fruitful period was in the 1970s and early 80s, where he participated in many of the significant British climbs in the Himalayas and beyond. A year before the Everest South West Face expedition, he’d been a vital cog in the team that reached the summit of Changabang in the Garwhal Himalaya.

Then, in 1977, came the epic of Baintha Brakk or, as it is more commonly known, the Ogre. Chris Bonington and Scott reached the summit but Scott fractured both his legs just above the ankle during an icy rappel from the summit. The pair managed to get down to a high camp and meet up with the rest of the team but a terrible storm blew in. With dwindling supplies, the group made an improvised retreat, eventually making it back to basecamp after descending for a week. The mountain would not be climbed again for 24 years.

The first ascent of Kanchenjunga’s North Ridge in 1979, alongside Joe Tasker, Peter Boardman and Frenchman Georges Bettembourg, was perhaps his crowning glory. The climb was achieved in alpine style with no supplementary oxygen. With Rick White, Bettembourg and Greg Child, he opened up a stunning new route, the beautiful Ganesh arête, on Shivling in 1981. Similarly, a 1982 alpine style ascent of Shishapangma’s South Face, alongside Alex MacIntyre and Roger Baxter-Jones, was widely lauded.

In 2011, he was awarded the Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement award, the third recipient of the prize after Walter Bonatti in 2009 and Reinhold Messner in 2010. The judges described him as a ‘visionary’. In his later life, Scott founded Community Action Nepal and worked tirelessly to improve lives in the region. It was a cause that was understandably close to his heart. He died from cancer in December 2020.

Joe Tasker and Peter Boardman

The 1970s and early ’80s were something of a golden era for British mountaineering at a time when siege style expedition tactics were making way to a fast and light approach in the Greater Ranges. Many notable first ascents occurred during this period by characters such as Al Rouse, Brian Hall, Rab Carrington – the founder of popular outdoor clothing brand Rab – and Alex MacIntyre. Two of the most prolific British mountaineers during this time were Joe Tasker and Peter Boardman.

Tasker’s first foray into the Himalayas in 1975 turned into something of an epic. After successfully climbing Dunagiri in India’s Garhwal Himalayas, he and partner Dick Renshaw ran out of food and became separated during the descent, with Renshaw suffering frostbite in his fingers. During the trip, Tasker’s eye had been caught by a stunning nearby peak, Changabang, the Shining Mountain. He returned the next year with Boardman and the pair pulled off an audacious climb of the mountain’s west face – an incredible achievement.

Prior to Changabang, Boardman had taken part in the Bonington-led expedition on the South West Face of Everest in 1975, the first to successfully ascend one of the mountain’s faces. He summited the day after Dougal Haston and Doug Scott alongside Pertemba, the expedition’s principal Sirdar. By 1979, Tasker and Boardman had been partners on various expeditions and they joined forces once more, along with Scott, to successfully ascend the unclimbed North Ridge of Kanchenjunga – a career highlight for all three. Further success followed in 1981 with an alpine style ascent of China’s Kongur Tagh, the highest peak in the Pamir Mountains.

On May 17, 1982, while attempting a new route on Everest’s North East Ridge, Tasker and Boardman were seen moving towards the second of The Three Pinnacles, a hugely difficult section of the ridge above the yawning abyss of the Kangshung face. It was to be the last time they’d be seen alive. Boardman’s body was discovered by expeditions in 1992 and 1995. Tasker’s body has never been found.

Both were talented writers and their adventures live on in their books Savage Arena and Everest the Cruel Way (Tasker), and The Shining Mountain and Sacred Summit (Boardman). Boardman’s The Shining Mountain, which tells the tale of the 1976 ascent of Changabang, is considered a classic. Their legacy also lives on in the Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature, which is an annual award presented at the Kendal Mountain Festival.

Alison Hargreaves

Born in Derbyshire in 1962, Alison Hargreaves’ love of the mountains began from an early age when she’d go hiking and scrambling with her father. With the English Peak District’s excellent rock climbing on her doorstep, she had the ideal training ground for the adventures to come, though it was mountaineering that would capture her imagination.

In 1986, she headed for the Himalayas with American great Jeff Lowe. Along with Tom Frost and Mark Twight, they put up new routes on Nepal’s saddle-shaped Kangtega. Incredibly, in 1988, she climbed the notorious North Face of the Eiger while five months pregnant with her son, Tom. She was back on the alpine north faces in 1993, this time achieving the incredible feat of climbing them all in a single season – the first person in history to do this. Fittingly, her son, Tom Ballard, would later emulate this achievement becoming the first person to solo climb all six of the Great North Faces of the Alps in a single winter season, between December 2014 and March 2015, but that’s another story…

Perhaps her most celebrated achievement came on May 13, 1995, when she became the first British woman to climb Everest solo, without Sherpa support and without the use of supplementary oxygen. She followed this up by travelling to Pakistan to climb K2 the same summer. After waiting out the weather for a suitable window, she achieved the summit on August 13. However, conditions deteriorated in devastating fashion, lashing the mountain with winds in excess of 100mph. Seven mountaineers lost their lives, including Hargreaves, her burgeoning career cut short at the age of 33.

In a cruel twist of fate, her son Tom also died while attempting to climb Nanga Parbat in 2019. Alison’s and Tom’s stories form the subject of the 2021 documentary film The Last Mountain, which features in our list of the best climbing films.

Martin Moran

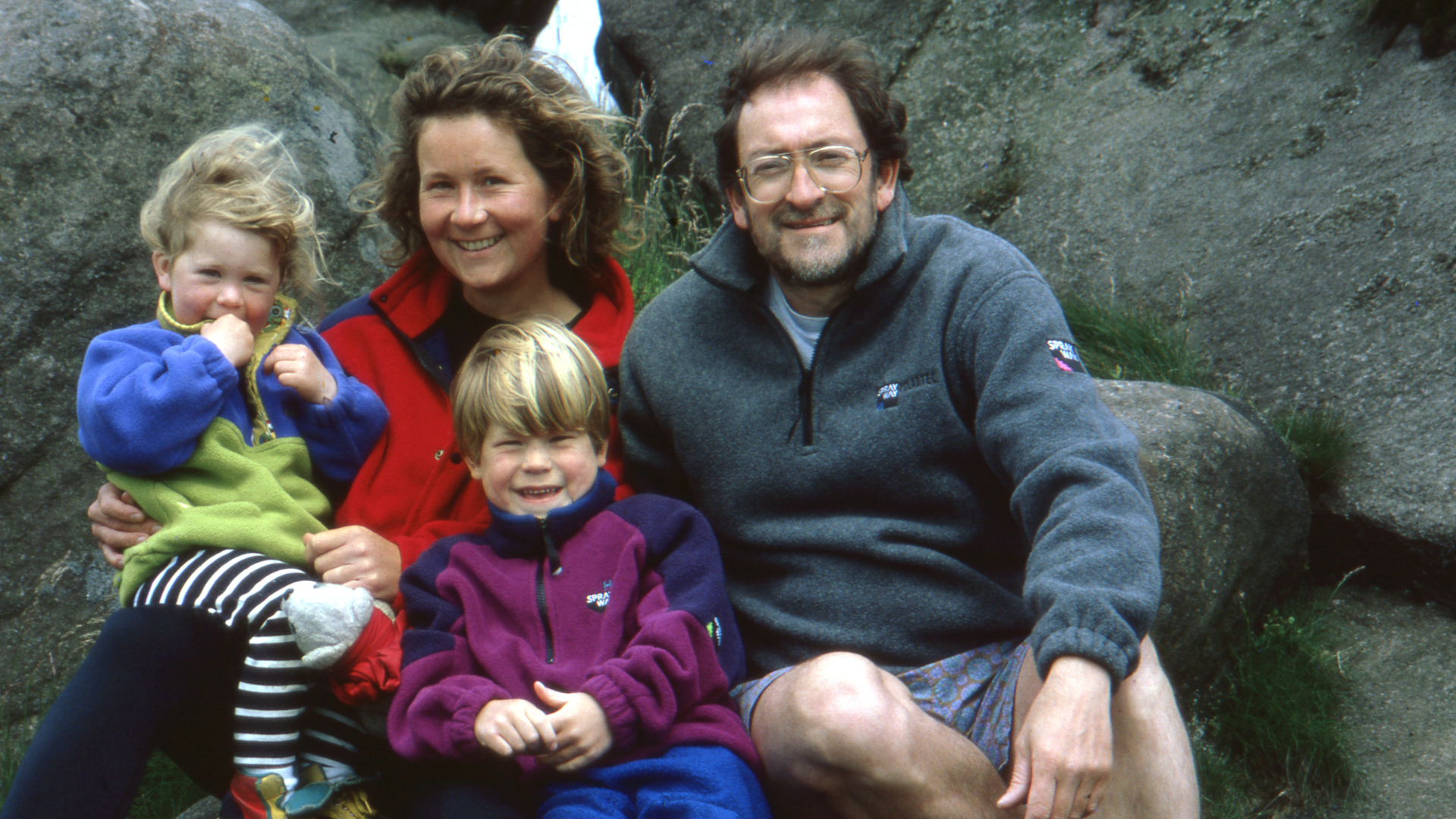

Martin Moran, born in 1955, appeared on the mountaineering radar when he became the first person to climb all of Scotland’s Munros (prominent peaks over 3,000 feet) in a single winter season, a feat of endurance and skill that’s only been repeated a handful of times to this day. It took him just 83 days, ably assisted by his wife Joy, who drove a campervan to provide a mobile basecamp for the effort.

Both a prolific climber and someone who moved with incredible speed in the mountains, he’d go on to achieve great things in the Scottish Highlands, where he lived with his wife and children. He made a significant contribution to Scottish Winter climbing, putting up over 100 new routes and climbing some of the hardest winter routes imaginable, particularly up on the spectacular big walls of the Northwest Highlands.

However, his legendary exploits weren't fixed to the Highlands. In 1993, he and climbing partner Simon Jenkins achieved a continuous traverse of the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps, the first people to do so in a single push. It was a similar undertaking to Kilian Jornet’s remarkable 19-day effort in summer 2024, as Moran and Jenkins travelled between the different ranges on foot or by bicycle, taking 52 days to complete the adventure.

He also made several first ascents in the Indian Himalayas, including Nanda Kot in 1995 and Nilkantha in 2000. His life was tragically cut short when he was killed in an avalanche on Nanda Devi in May 2019.

Mick Fowler and Paul Ramsden

The fact that this pair have scooped no less than eight Piolets d’Or awards – very much the Oscars of mountaineering – between them is a measure of Mick Fowler and Paul Ramsden’s talent and achievements.

Ramsden is the most decorated alpinist in the award’s history, with five wins. Three of these were alongside Fowler, for their alpine style ascents of the north face of China’s Siguniang in 2003 and India’s Prow of Shiva in 2013, as well as for the first ascent of Nepal’s Gave Ding in 2016. Ramsden then went on to win two further awards for his ascents of Tibet’s Nyainqentangla South East with Nick Bullock in 2017 and the Phantom Line of Nepal’s Jugal Spire with Tim Millar in 2023.

Fowler, born in Wembley, London in 1956, first garnered recognition as a leading trad climber. He was one of the first British climbers to free an E6 graded route when he sent Linden on Curbar Edge in the Peak District National Park in 1976, while he’s made many notable first ascents on technically challenging sea cliffs and stacks. His winter climbing exploits saw him free the first consensus Scottish Winter grade VI route on Ben Nevis’ The Shield Direct in 1979. His later career has seen him take lightweight alpine tactics to unclimbed 6,000 and 7,000-metre peaks in the Himalayas. More recently, in September 2024, despite having recently recovered from cancer, Fowler achieved a first ascent of Pakistan’s Yawash Sar alongside 74-year-old Victor Saunders.

Yorkshire-born Ramsden, despite his accolades, shuns publicity, with no sponsors or presence on social media. Like Fowler, his preferred approach to mountaineering is a self-sufficient, lightweight style and the pair have achieved a string of impressive, technical first ascents of unclimbed peaks in the Himalayas.