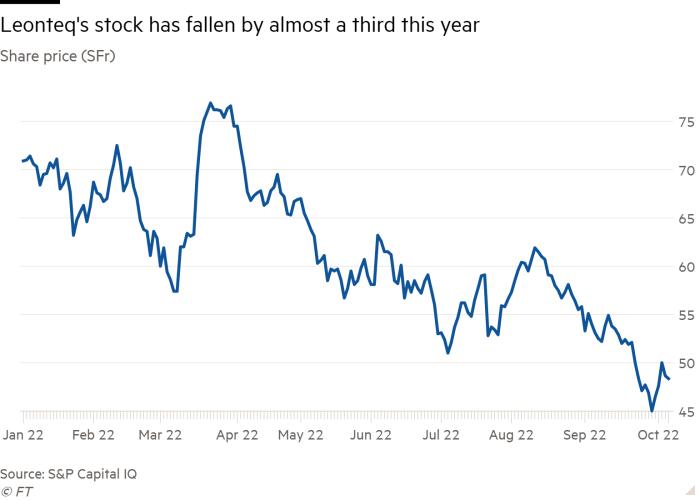

Whistleblowers have accused EY of whitewashing suspicions of money laundering and tax evasion in an investigation it conducted this year for longstanding client Leonteq.

At the heart of the whistleblower complaints are two trades that the company, a listed fintech that designs bespoke investment products, created for a French workers co-operative society at the start of 2021.

The whistleblowers said the trades should have been reported to French authorities as suspect on grounds of potential money laundering and tax evasion, after it was discovered that large commissions were routed to a British Virgin Islands company instead of the broker in France that sold the investments on Leonteq’s behalf.

They have also accused Leonteq and its internal auditor EY of failing to take basic steps to investigate.

Documents and recordings related to the trades, reviewed by the Financial Times, raise questions about weak controls, a culture of rule breaking and poor governance at Leonteq, which traded SFr29bn (£24bn) of structured products last year.

Leonteq said it had “a strict zero tolerance policy regarding non-compliant business behaviour”, and that all allegations were “managed, monitored and reported with due care and process”. It said “all investigations found that there were no material shortcomings” and that it was “committed to upholding the highest standards of integrity and compliance”.

Leonteq commissioned EY to look into the two trades and related issues. The accounting firm’s subsequent report described problems with internal controls and an “an absence of email and phone-record evidence”, but said “no indication exists that would justify the allegations of money laundering or tax evasion”.

Although the firm has for several years advised Leonteq’s board on the “adequacy and effectiveness” of internal controls, and whether the group complies with “applicable policies, procedures and the rules and regulations”, according to annual reports, EY’s report on the matter indicated it did not take steps to verify or establish some basic facts about the trades.

“All EY had to do was call the co-operative,” commented one whistleblower.

When the FT did that, it heard a version of events that suggested the whistleblowers were right that something was awry.

The co-operative is ID Formation. Based in Lille with branches all over France, it trains workers and job seekers. President Eric Faidherbe told the FT: “I’m involved in a bit of a crazy story here.”

He said the co-op holds some of its assets as structured products, and was joined on the call with the FT by the man whose small firm manages such assets, Marc Pruvost.

In March 2021, ID Formation purchased two €750,000 securities related to the share prices of telecom group Orange and steelmaker ArcelorMittal, both of which were issued by Leonteq. The sale of the two products was a regulated transaction, with the securities held by a French custodian.

Pruvost said he arranged the trades for the co-operative through a Paris brokerage called i-Kapital. Such brokers are at the heart of Leonteq’s business model, selling its bespoke securities to clients in return for commissions.

What made the two trades unusual is that neither Pruvost nor i-Kapital were paid fees. Pruvost told the FT he waived his to achieve better terms for ID Formation as a good client, and that the broker was supposedly doing the same to win Pruvost’s business for the first time: “i-Kapital told me they wouldn’t take a commission,” he said.

Somebody was paid, however. Leonteq sent €120,000 offshore, equivalent to an 8 per cent cut on the two trades, to a company in the British Virgin Islands called Ladoga Capital, which had a relationship with Leonteq’s Middle East sales team.

This fact was uncovered only in June 2021, following a review of emails by Leonteq compliance when a junior employee in Paris abruptly left.

Yet the paperwork for the securities listed only the involvement of Pruvost’s Lille business Eurocap Finance, and i-Kapital in Paris. At the same time, Leonteq’s systems credited its Middle East team with arranging the trades, not the Paris office that had a relationship with i-Kapital.

An audit trail of official communications related to the transactions, a regulatory requirement, could also not be found by Leonteq’s compliance team; Ladoga Capital was not authorised to distribute investment products within the EU; and Leonteq’s Middle East sales team had no official relationship with i-Kapital.

Whistleblowers said the missing information was partly the result of a work environment where informal messaging was common. “A lot of people internally and externally communicate by WhatsApp,” one said.

Use of unofficial messaging channels in the financial services industry is currently in the sights of regulators; the US government recently announced a $1.8bn settlement with 11 banks and brokers related to “pervasive off-channel communications”.

Leonteq said WhatsApp and other messaging apps “are not allowed for conducting business with clients”, and that “any breaches would result in appropriate disciplinary actions”.

Whistleblowers also claimed there seemed to be a culture where commercial interests sometimes trumped compliance.

For instance, they said that the Middle East team credited as arranging the two trades by Leonteq had relocated from London to Dubai at the start of 2021 but continued to service existing clients without all of the appropriate paperwork.

This problem caused laughter when it was discussed on a call for compliance officers on March 10, 2021, on a recorded line. “We’re breaking all sorts of rules in Dubai by continuing to operate,” said one.

The head of compliance for Europe, the Middle East and Africa replied: “We know that, it’s suboptimal.”

Leonteq said it “takes its regulatory duties very seriously and no material shortcomings occurred”.

Then, during the summer last year, a row developed inside Leonteq’s compliance team about whether the trades for ID Formation were suspicious and should be reported to Tracfin, the French financial intelligence agency.

A compliance officer questioned the offshore payment in a June 15 2021 email: “Is it a free service for someone . . . a way to layer funds?”

Layering is a process that can be used to disguise the source of funds by passing money through layers of transactions or financial instruments.

A whistleblower told the FT that “we know the end investor is in France. The BVI is a smokescreen.” The person said that it raised the question of whether the arrangements were to avoid disclosing the commissions as taxable French income.

In another recorded call, conducted in September 2021, a Leonteq compliance officer appeared to share that concern. He said: “Ladoga was not involved in that trade, that is my fear. We have seen it in another case five years ago. My fear is that Dubai talked to either Eurocap or i-Kapital.”

Leonteq told the FT that “compliance is an absolute priority”.

As compliance investigated, a September 2021 email from Pruvost muddied the water: it said that i-Kapital appeared on documents for the trades by mistake.

Pruvost told the FT that he wrote the email at the request of i-Kapital, which asked him to obscure its involvement in the two trades due to what he called “an internal commercial war between Leonteq Paris, Switzerland and England”. He said i-Kapital did not want to upset the Leonteq Paris salesman that it was supposed to trade with.

i-Kapital did not respond to questions it asked to receive by email. Ladoga was placed into voluntary liquidation by a Panamanian liquidator in August, after the FT contacted other parties to the alleged suspect trades. It could not be reached for comment.

In October 2021, the internal argument about what to do and how thoroughly to investigate was escalated to Leonteq’s board in an email that alleged that parts of the organisation had resisted a thorough review of several suspect trades, including the two for ID Formation, to protect a high-performing salesperson in Dubai, and to avoid conclusions that would show a “complete failure of our legal and compliance framework”.

The board decided to appoint EY in Switzerland to investigate the suspect trades, a move one whistleblower compared to marking its own homework. Leonteq said the investigation was not conducted by its usual EY internal audit team.

As the saga played out Leonteq was advised by a law firm about its French legal obligations: the group is required to file a suspicious transaction report for any sums or transactions that it knows, suspects, or has good reason to suspect originate from tax fraud.

Then this year, in a memo dated January 20, Leonteq compliance concluded that filing a suspicious activity report in relation to the two trades was “not deemed necessary”.

EY endorsed that conclusion in a February 15 2022 “issue report”, even though it had not established who sold the securities to ID Formation and how they did so.

The firm found that six trades, including the two for ID Formation, had “problematic aspects”, that “uncertainty remained about the distribution chain” and that it was not possible to confirm some suspicions raised due to “an absence of email and phone-record evidence”.

EY seemed to accept that Ladoga was a bad actor in the affair — that it had possibly distributed products into France without the contractual or regulatory right to do so. What EY did not establish was the identity of the other parties to the two trades — i-Kapital, Eurocap Finance and ID Formation. Its report also did not consider why i-Kapital would use Ladoga as an intermediary when it had its own direct relationship with Leonteq in Paris.

What EY did find was that, if business was conducted as the Middle East sales team described, this would mean Leonteq “would have no control” over whether the companies distributing its products were breaking its rules.

That verdict came five days after Leonteq published its annual report, in which EY was again said to provide the board with “independent and objective assurance of the adequacy and effectiveness of the internal control system.” EY declined to comment, citing client confidentiality.

One whistleblower said: “It’s a complacent investigation by EY. That’s the problem right there. Controlling the distributors is a regulatory requirement, but weak controls attracts shitty business. Turning a blind eye to potential money laundering is to become complicit.”