JUSTICE / MAY 2023

Where the Children Are Buried

Thousands of Indigenous children died at residential schools across Canada. This is the story of one community’s search for unmarked graves

BY ANNIE HYLTON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SARA HYLTON

Published 6:20, Mar. 29, 2023

This story contains details about residential schools that some readers may find disturbing.

Jenny Rose spyglass was three years old when the men came for her. It was September 1944 in present-day west-central Saskatchewan, where the prairie grass grows wild and the contours of the sky seem infinite. Spyglass’s family home—in Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Lean Man First Nation—lay nestled in the Eagle Hills, surrounded by wheat fields, chokecherry, and willow, land roamed by elk, lynx, and coyotes. She lived in one of several Indigenous communities in the vicinity of the Thunderchild Indian Residential School, run by the Roman Catholic Church, some sixty kilometres away.

As Spyglass recalls, her family lived in poverty—her father had recently been deployed by the Canadian military, leaving her mother to care for six children. That fall day, Spyglass remembers, a black vehicle drove up the gravel road and approached her house. A few men emerged: federally appointed Indian agents—who enforced Ottawa’s policies across First Nations reserves and Indigenous communities in Canada—and two priests. The men pointed at Spyglass as her mother pled. “I hung on to my mom,” she says. The men snatched her from her mother’s grip and tossed her, along with her two elder brothers, Martin and Reggie, into the back of the vehicle. During the drive, Spyglass fell asleep and later awoke to children sobbing and gathered near another vehicle. All of them had been torn from their homes in neighbouring reserves—Moosomin, Poundmaker, Sweetgrass, and Red Pheasant, among others—after their parents were threatened with jail or fines if they resisted their child’s attendance at the Thunderchild school. The children were transported to the school, located in what is now Delmas, a remote hamlet off the Yellowhead Highway.

When Spyglass arrived at the sprawling facility, it housed up to 130 children—the girls were sequestered in the south side and the boys in the north—and they slept in dormitories on the upper level of the main building. “I had long, beautiful braids. My mum used to braid my hair. They chopped my hair and put them in a garbage,” Spyglass recalls. “They took my clothes off my mum made for me and dumped them in a garbage.” Like the other girls, Spyglass was made to wear an apron-like uniform. Children were called savages and punished for speaking their native tongues. Spyglass, who spoke Cree and some Assiniboine, did not understand English. She spent her days hungry and alone, cutting out doll pictures from shopping catalogues. She recalls older girls stealing food from the kitchen, where they worked, to feed her and the younger ones—they ate dry bannock, beans, and porridge, but the food was never enough. At the school, girls were made to do domestic chores, and the boys were forced to farm.

The school had been built on fertile land that was later surrendered to settlers. The 1876 Indian Act, a federal law that was explicitly designed to carry out Canada’s assimilation agenda, had created the reserve system—wherein a plot of land is set aside by the government for a First Nation whose members are wards of the state—and paved the way for the residential school system. Later amendments to the law made it mandatory for “every Indian child between the ages of seven and fifteen years who is physically able” to attend. In the 1940s, Canadian officials discussed elements of the Indian Act with their South African counterparts. That country’s apartheid system, some scholars allege, was later imbued with these elements. Though amended, the Indian Act is still in effect today.

Several parents across Canada physically removed their children from residential schools or refused to send them at all (often forgoing their monthly rations and risking jail), hid their children in basements and forests, and petitioned the federal government and created political organizations. In the 1890s, despite it being illegal for Indigenous peoples to hire a lawyer (and it would remain so until 1951), two sets of parents in Ontario engaged a solicitor to have their children discharged.

The Thunderchild Indian Residential School (originally called St. Henri of Thunderchild and later known as the Delmas school) was run by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, under the administration of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Prince Albert. By the time Spyglass and her brothers arrived, it had been operating for some four decades. The aim of the entire residential school system, according to deputy superintendent of Indian affairs Duncan Campbell Scott, the civil servant who oversaw the expansion and brutality of the system, was to “get rid of the Indian problem.” As noted in the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC)—a six-year nationwide effort established, in part, to document the legacy of residential schools—the system was built to cause “Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious and racial entities in Canada.” Between the 1880s and late 1990s, at least 139 federally funded residential schools were run by Christian churches—a system that was at the centre of a national policy of cultural genocide. (One of the last schools to close in Canada, in 1997, was in east-central Saskatchewan.) More than 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children attended as residential or day students. John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, famously said before the House of Commons in 1883: “When the school is on the reserve the child lives with his parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write.”

At the Thunderchild school, the children attended mass at least every Sunday as part of their assimilation. They were also forced to seek repentance for their sins. “In confessional, the priest would ask if I had sex with anybody,” Spyglass recalls. “I didn’t know what that is. I was too small . . . And then he would take my hand and say, ‘Can you touch me in my legs?’” He would then give her a chocolate bar. One priest, she says, “always wanted to kiss the little girls, and we would take turns pushing, ‘Now you go, you go, you go, tell your sins,’” she recounts. “How can we have sins?” In 2007, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement came into effect and included a process for claims of sexual or physical abuse that occurred at residential schools across Canada—it received nearly 40,000 claims.

One day, when she was about four years old, Spyglass learned that her brother Reggie, a year older, had become ill. She and Reggie were close—best friends. Reggie was isolated in a small room, and nobody was permitted to see him. “They just let him suffer,” Spyglass says. “He never made it home.” She didn’t know the cause of his death at the time, but her family later surmised it was tuberculosis, a disease that was then at least five times more likely to infect and kill First Nations people living on reserve and over sixty times more likely to kill children in residential schools.

The school itself was poorly maintained. In 1940, an inspector declared it a fire hazard and advised its closure. It remained open for another eight years. The school was overcrowded, and students suffered from a host of illnesses: scarlet fever, typhoid, jaundice, and pneumonia. Students were alleged to have died by suicide or under suspicious circumstances, including being beaten to death. At least one student went missing and was never seen again, likely freezing to death in the harsh and remote environment after running away. Seven percent of the hundreds of students who attended the school died. According to Jack Funk, a former Department of Indian Affairs superintendent of education in Saskatchewan, death rates were up to five times higher than those for non-native students attending provincial schools. “That’s what hurts the most, is my brother had to die,” Spyglass says.

For decades, Indigenous communities and families had raised the alarm about children who attended residential schools and never came home, but neither the schools nor the government made any systematic effort to record their deaths. Estimates range from several thousand to upward of 25,000 across Canada. Because the Department of Indian Affairs regularly refused to ship bodies home due to the cost, children’s remains were often interred on site or in local graveyards. Those lands were often then sold and leased and disturbed by commercial and agricultural use. “Subjected to institutionalized child neglect in life, they have been dishonoured in death,” noted the TRC, which incorporated the testimonies of nearly 7,000 survivors. Most records that did exist, including cemetery locations, were destroyed or hidden by the federal government and the Catholic Church. (Between 1936 and 1944 alone, the government destroyed upward of fifteen tons of paper.) Often, burial sites are known only through local oral histories—as is the case in Delmas.

The TRC called for the federal government to create a national online registry to help identify all unmarked cemeteries and gravesites. Former prime minister Stephen Harper’s government stymied early efforts to investigate the scope of deaths at residential schools, the TRC report found. And Jean Chrétien, two decades before becoming prime minister, had effectively overseen the residential school system as minister of Indian affairs and northern development between 1968 and 1974. Chrétien recently denied hearing reports of sexual and physical abuse during his tenure as minister, even though there is documentary evidence to the contrary. He also compared the students’ experience of attending residential schools to his experience, as a child, attending a boarding school, where he ate baked beans and oatmeal. In 2015, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to implement all ninety-four of the TRC’s Calls to Action. According to Indigenous Watchdog, a non-profit, only thirteen have since been fully realized.

For First Nations communities, the “accounting of Indigenous death feels relentless,” wrote Erica Violet Lee, a nêhiyaw writer, scholar, and member of Thunderchild First Nation, in the Guardian. “Our grief and our lives are not reducible to numbers or statistics.” Since the summer of 2021, First Nations across Western Canada have located possible unmarked graves of hundreds, if not thousands, of children on former residential school grounds. It wasn’t until then that, for many Canadians and much of the world, the country’s dark colonial legacy was brought into sharp focus and laid bare.

In August 2021, photographer Sara Hylton, my twin sister, and I visited Delmas, about a four-and-a-half-hour drive northwest of Regina, Saskatchewan’s capital, where we were born and raised. Karen Whitecalf, a fifty-seven-year-old Cree woman from Thunderchild First Nation, had devoted weeks to planning several searches for unmarked graves using ground-penetrating radar. She had also planned a traditional ceremony to accompany the process. She had invited us to observe the ongoing search and to speak with survivors and community members.

That June, Whitecalf, then an administrator with Battlefords Agency Tribal Chiefs, a tribal council of seven First Nations in Saskatchewan, was invited to a meeting with BATC directors and staff. Neil Sasakamoose, the CEO, told the team that an engineering firm had approached him about volunteering its time and equipment to search for unmarked graves at former residential school sites using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) detection. The process involves identifying anomalies from high-frequency radio waves that are penetrated into the earth and reflected back. That May, the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nations government had announced that more than 200 probable burial sites had been identified using GPR after children’s remains were found in what was known to be a graveyard at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in central British Columbia. The news swept across Canada and around the world.

Within days of the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc announcement, the federal government, facing an onslaught of criticism for long ignoring residential school deaths, committed $27 million to help communities identify and locate children’s remains. Many called for a papal apology for the Church’s role. (Over a year later, during a visit to Canada, Pope Francis apologized for the “evil” of church personnel who worked in the schools and the “catastrophic” effect of the school system on Indigenous families.) Initial requests for financial assistance surpassed a hundred, and the government soon expanded its commitment. SNC-Lavalin, a Montreal-

based engineering and construction giant with nationwide offices, then sent a letter to BATC and dozens of First Nations across Canada, offering assistance.

SNC-Lavalin’s offer to BATC, though, was met with skepticism, particularly given the company’s checkered past. (It had been embroiled in a 2019 corruption scandal, which contributed to the resignation of justice minister and attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould, after the company gave bribes for contracts in Libya.) Terence Clark, a University of Saskatchewan researcher and assistant professor specializing in community-based archaeology projects, told the Globe and Mail he was “worried that First Nations might end up receiving shoddy analyses after rushing to commit to these projects amid pressure to find remains on their territory. . . . If it’s not good work, that just adds to the trauma.” Private contractors may have the technology, but do they have the required skill and sensitivity, others asked.

BATC discussed the controversy but chose instead to focus on the task ahead and, for what would otherwise be a cost-prohibitive process, welcomed SNC-Lavalin’s pro bono offer. (Other organizations had approached BATC hoping to profit from the searches.) “Why would we turn away help? It’s such an important project,” Whitecalf later told me. In the meeting, she agreed to head the project. “I’m from Thunderchild. My dad, my Mooshum [grandfather] both went to a residential school,” she says. “So that’s what got me to raise my hand.”

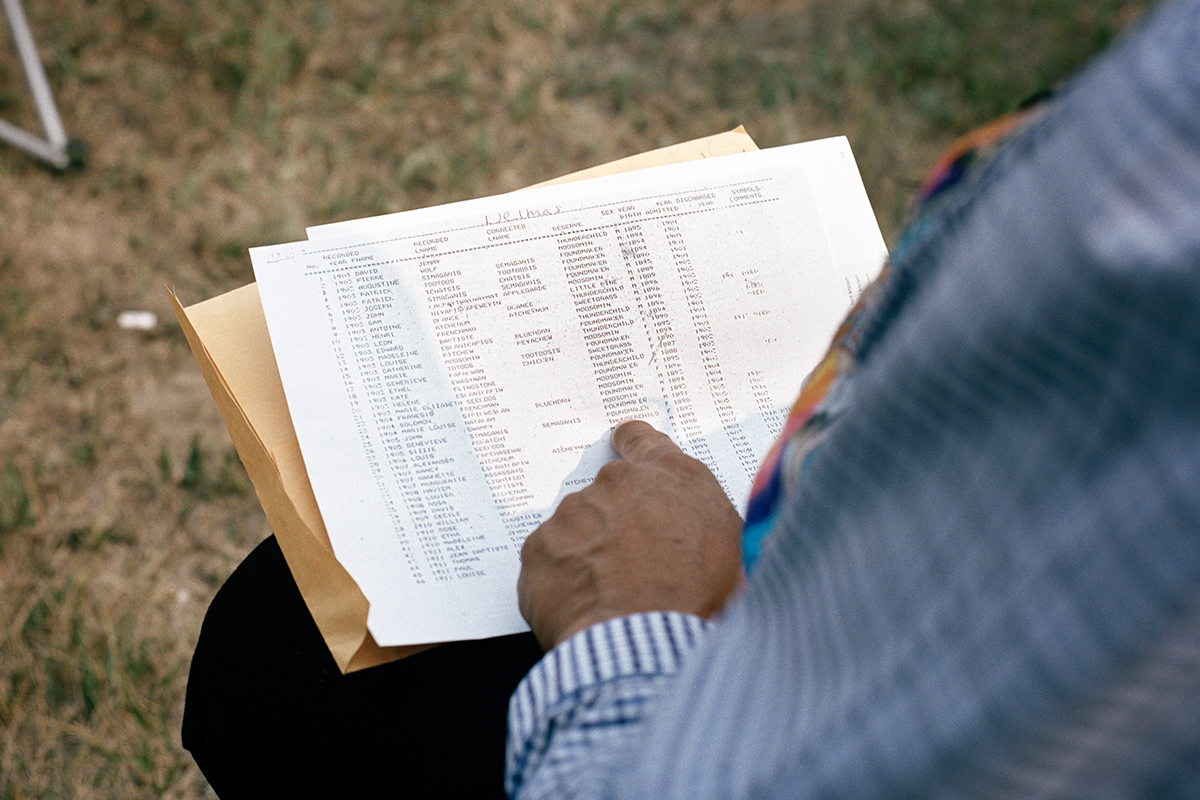

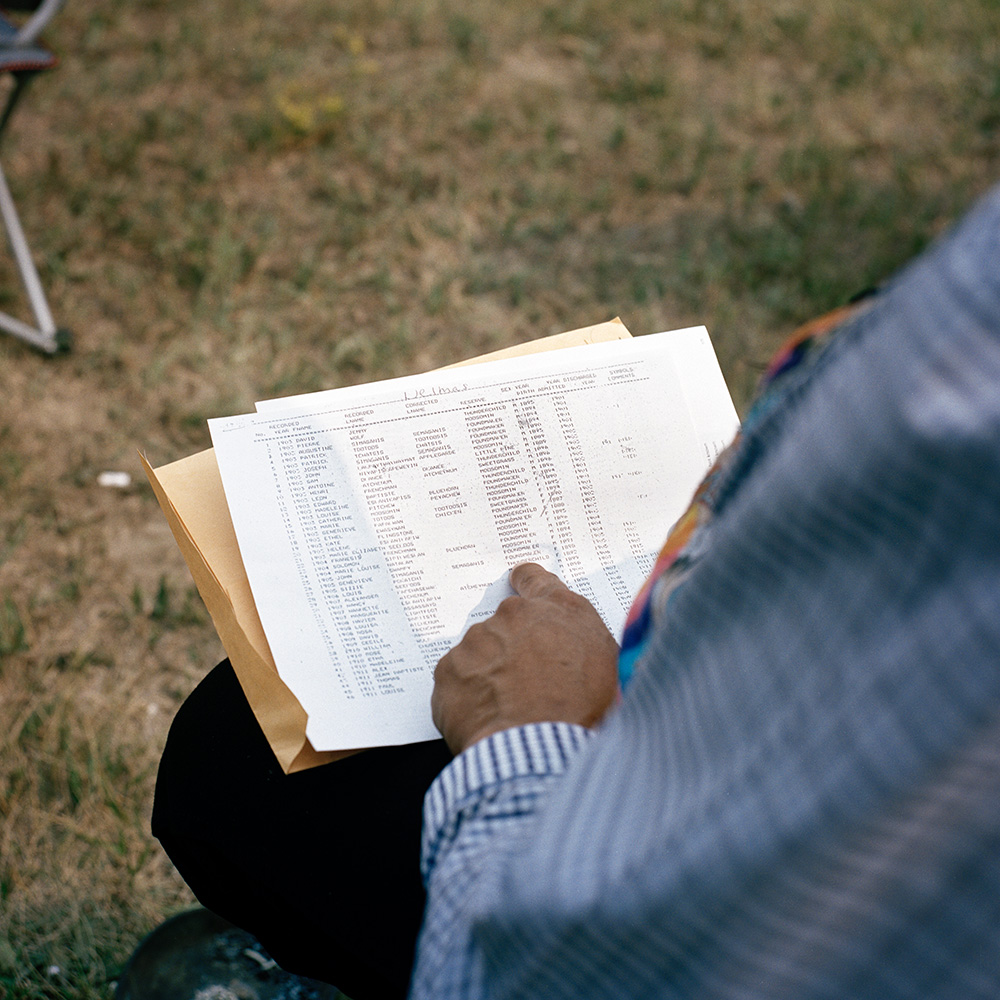

Whitecalf consulted with elders and survivors across the region to ascertain the first search location—and decided to go to Delmas. Unlike the nearby Battleford Industrial School—where, in 1974, archaeology students and staff from the University of Saskatchewan exhumed, identified, and reburied remains from more than seventy graves, most belonging to students who had attended the school, and later marked the site with a memorial—Delmas, according to Whitecalf, was relatively “untouched.” Historical records have been difficult to locate: many are spread across provincial and national archives or kept by the Church. As Whitecalf sought to compile records and oral history in the Delmas area, she learned tragedy had struck her own ancestral tree years earlier. She obtained an incomplete student enrolment list of more than 600 Thunderchild Indian Residential School attendees, only to discover that her grandfather, whose Catholic name was Jimmy David (spelled Jemmy on the list), was the first student registered at the school in 1901. (Residential schools kept poor records, and many students’ names were incorrect or missing from official documents, making it difficult for family members to identify their relatives.)

While Whitecalf, a descendant of Chief Peyasiwawasis (Thunderchild), first heard the history of her people as a teenager, she said her ancestors attending residential school had become a “well-kept secret.” Her grandmother would gather her grandchildren and pass down stories of the past, but “we have been conditioned not to talk,” Whitecalf told me. As part of her work on this project, she has made it her mission to make known publicly what she said has long been a legacy of shame and heartache.

That July, seventy-seven years after Spyglass first set foot in the Thunderchild residential school, she walked the former school grounds, now private property, with Whitecalf by her side. Spyglass spoke to a group of fifty or so people who had gathered for the first search. Among them were members of the public, residential school survivors, and local media. Spyglass wore two braids, now grey with age, that ran down the front of her blue jacket. This land “is where they took my culture away,” she said. It’s “where my brother passed away.” Whitecalf wore a traditional red ribbon skirt and embraced Spyglass, stroking her back as she wept. “It hurts,” Spyglass said. She went home that night and had flashbacks of Reggie. The tears didn’t stop. “I don’t know what’s going to happen,” she later told me. “Even though they will find some bodies, baby bodies up there, in my mind, I picture they all went to a good place.”

“Even though they will find some bodies, baby bodies up there, in my mind, I picture they all went to a good place.”

Indigenous peoples inhabited the land that is now Delmas until Canadian Crown representatives and Cree and Stoney First Nations leaders signed Treaty 6 in 1876. (Chief Thunderchild initially rejected the treaty, hoping for better terms, but, with the collapse of the buffalo hunt, later signed an Adhesion to Treaty 6 in 1879.) The treaty was one of a series known as the Numbered Treaties that the federal government signed with Indigenous peoples across central and western Canada to gain territory for development and white settlement. In exchange for rights, titles, and privileges relating to more than 300,000 square kilometres of land, the government promised to set aside reserves, including one for Thunderchild First Nation.

Catholic missionaries had recently arrived in the area to teach catechism to local Cree and Métis families. In 1890, a bishop established a school, which Chief Thunderchild opposed, and he later led a movement to have it torn down. In 1900, Father Henri Delmas, who had arrived from France via Ottawa a few years earlier with the aim of creating a French colony, received permission from the federal government to rebuild the school, this time as a Roman Catholic residential school abutting the Thunderchild reserve.

Shortly after the school was built, Father Delmas and government officials began asking Chief Thunderchild whether he would sell his land. (In the early twentieth century, taking over First Nations reserves had become a burgeoning nationwide practice. According to Funk, the former superintendent, thirty-six bands in Saskatchewan gave up all or some of their reserves.) Chief Thunderchild consistently turned down the proposition. Eventually, Father Delmas, officials from the Department of Indian Affairs, and clergy members succeeded in pressuring the men of Thunderchild to surrender the land, considered rich for farming and favourable to newcomers in Delmas for its proximity to the newly built railway.

In a letter to the minister of interior in 1908, Father Delmas claimed it had been “a very difficult task to get [the Thunderchild band of Indians] to accept the terms.” Because he “worked hard” to get them to “surrender their reserve,” as one of the original settlers living in Delmas for eight years, “I think the government should give me a chance to establish a Catholic Colony on this reserve.” Thunderchild First Nation was forcibly relocated to an area northwest of their original reserve. It was unsuitable for farming, and the nation had trouble sustaining itself there.

Chief Thunderchild later wrote a letter to Duncan Campbell Scott opposing the fact that children from the nation would be attending a Roman Catholic school and that they would be forced to travel so far from the reserve to attend: “A spruce tree taken while young from a low-lying moist soil when transplanted into light soil dies in most cases. If it lives, it will be but short and stunted, where it would have been tall and straight had it been left in its natural soil. The system is not natural, it seems artificial and the fruit of it, so far as I can see it in my Reserve and elsewhere has been very poor. Many a pupil has come home to die.”

In 1909, an auction was held for the surrendered land, and Delmas purchased several sections of it—an area sufficient for the twenty-five families who planned to settle there, according to the book Delmas: A Harvest of Memories. Nearly a century later, the First Nation received a $53 million financial settlement from the federal government after submitting a claim that the land surrender was “null and void.”

Funk wrote about the surrender in a 1989 book, Outside, the Women Cried, whose title refers to the women who wept outside the log schoolhouse where the men of Thunderchild signed away their land. Survivors and elders frequently refer to the book as one of the few texts that represent the truth of what they had lost. One recent Christmas, Whitecalf gifted the book to her two daughters. “It’s important they know their history,” she says. “Thunderchild was moved to where they are now. I’ve taught my children . . . not to be discriminated against anymore,” and to be proud.

In the winter of 1948, when Spyglass was around eight, the girls in her dormitory were trying to sleep but they lay there restless. “All of a sudden, the nuns started screaming and everybody jumped up,” she recalls. A cloud of dense black smoke emerged from the basement. Spyglass put on her rubber boots and wrapped herself in a wool blanket as the nuns pushed her down the fire escape. Soon, the school was enveloped in a blaze large enough, Spyglass says, for her mother, all the way in Mosquito, to see. By then, Spyglass’s siblings (excluding Reggie) who’d attended the school had escaped home. (Almost all schools had runaways, and the occurrence became so common that government officials referred to it as an “epidemic.” But escape attempts could be ill fated, and Indian agents and police would often retrieve students and force their return; other escapees would perish while navigating their way through blizzards, on boats, or on foot.)

As embers from the inferno rained down, some children allegedly cheered. Nobody had died in the fire, and “everybody was happy,” Spyglass recalls. “We were all going to go home.” She spent the frigid night in a garage and took a train to the Red Pheasant stop the next day. Spyglass knew that her family lived near the railway track, so she walked south to the general store, where her mother worked. Soon, she saw a figure running toward her. As it got closer, she realized it was her brother Martin. He carried her about a kilometre until they reached the store. Their mother was waiting, sobbing. “From there on, everything my mom done, she never left me,” Spyglass says. “My mom was my doctor, my partner, my counsellor. She was my teacher. The school never gave me nothing,” she says, but “she gave me love.”

In 2021, filmmaker Floyd Favel released a documentary about the fire. He had spoken with the last remaining survivors and witnesses, who said a group of boys, tired of the poor treatment at the school, had warned students before deliberately burning the school down. “It was known for lack of food, abuse of the students, and that’s why many students were running away. They would always get caught, so it had resembled almost like a prison,” Favel told CTV News. The RCMP investigated the culpability of the four boys but later closed the case due to lack of evidence. The fire left the school flattened; it was never rebuilt. Instead, the land was cleared, with little physical evidence of the school left, and then sold to private owners, who cultivated it and built on it.

Over half a century after the fire, Whitecalf tried to locate former students and residents. Those still alive were in their eighties or nineties. She carried with her an aerial photo of Delmas, marking possible burial locations with an “X.” Through oral-history testimonies, Whitecalf pinpointed six locations, over a square kilometre, as possible burial sites. Neil Sasakamoose, the CEO of BATC, told the CBC, “We have some of the people that actually dug the graves for some of those people—that are still alive, and they’ve told us, ‘Right here is where I remember being.’”

Some of the remains, Whitecalf determined, may be down in a cemetery near the Saskatchewan River, where a recently discovered headstone was etched with the name Henry Atchenam (a misspelling of Henri Atcheynum). Lorie Whitecalf, the chief of Sweetgrass, and her aunt, Viola Whitecalf, relatives of Atcheynum’s, told me ancestors had passed down oral history that Atcheynum had attended the Thunderchild residential school for several years until he was beaten so severely that he died at the age of thirteen. (The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation identified him as one of the children who died at the school.) Church records indicate Atcheynum had died several kilometres away from the school while on Sweetgrass reserve, which the family says is a lie and doesn’t coincide with the timeline of his death. His is the only grave with a marking, and the family suspects it’s because his father was the chief of Sweetgrass, and the Church felt obliged to commemorate him.

Others still were perhaps buried across the road from the school grounds where the Yellowhead Highway runs; in the local Delmas cemetery or its outer perimeter, depending on whether they were baptized or not; in the graveyard of the former school; or elsewhere on its grounds, now a thirteen-acre private property. The search process, Whitecalf discovered, would be complicated. “There’s a chance we might not even find our children,” she told me. “The land was used, disturbed, and oral history says the remains were moved and reburied. It’s kind of disheartening. But we’re going to still keep looking.” The next step, she decided, was to approach the owners of the land where the school and its gravesite once stood.

In 2019, Montgomery learned that, on the northeast edge of Delmas, a thirteen-acre property with an 1,800-square-foot house had been repossessed by the bank. The house was in rough shape, sitting empty except for partygoers once in a while, and selling for a bargain. For McBain, the deal was too good to pass up. “Trailers are trailers, and this is a beautiful house,” she thought. But “it was very cheap, and now we know why.” That October, McBain and Montgomery purchased the land, planning it as their “forever home,” where they would retire and enjoy the sunken living room and large fireplace. They imagined family visiting, with great-grandchildren playing in a rumpus room and frolicking in the underground pool they hoped to build. They worked for weeks, repairing water and smoke damage, punctured walls, and broken doors. McBain took pride in her garden, planting flower beds of bleeding hearts and sunflowers and growing potatoes and carrots. They rented the hayfield and grain bin to local farmers to cover part of their land tax.

After moving in, though, they started hearing rumblings from neighbours about their land. “Did you know this was a graveyard and people are buried in your basement?” one asked. Montgomery was shocked. “Oh, ya, this was a residential school over here,” another said. At first, it was hard to believe. “But then the stories were all the same,” McBain says. The couple heard that the first private owner had kept the land relatively untouched for some twenty-five years; he had left part of it uncultivated, having understood that children were perhaps buried there. But the land was then passed on and disturbed when the successive owners excavated for a new basement and built a larger home. “They were digging out here and found bones,” says one neighbour, who also recalls the owners saying, “I hear that there might be graves here.” (According to locals, the husband died and the wife moved.) One local says her children had gone over to the property at the time and saw either a shoe or some hair. Others say the remains were found with beads. But the provenance of the remains was never examined, and authorities were never notified, locals say.

“Did you know this was a graveyard and people are buried in your basement?”

McBain found it hard not to worry, while digging in her flower beds, that she might unearth graves. The couple decided to forgo the pool, unsure of what they would uncover. In June 2021, news was emerging from two First Nations in Saskatchewan about preliminary findings of unmarked graves. Muskowekwan First Nation laid out thirty-five pairs of children’s moccasins and shoes on the steps of the nearby former residential school, the last one to remain standing in the province, to represent each unmarked grave it identified there. Cowessess First Nation then announced a preliminary finding of 751 unmarked graves near the former Marieval Indian Residential School.

One day that same month, McBain got an unexpected phone call. Whitecalf had managed to track down her number through local farmers. Whitecalf introduced herself and inquired about the land. At first, McBain was defensive. The planned search in Delmas had been announced publicly, but due to a misunderstanding about who owned the land, McBain and Montgomery had not been approached beforehand. McBain told Whitecalf that she was frustrated people were trespassing on her land. Whitecalf recalls saying: “It’s just totally different. My name is Karen, and I work for BATC, and I want to ask for permission to go on your land.” McBain softened, and Whitecalf suggested she visit her in Delmas. Whitecalf brought tobacco and a beaded pink lanyard as an offering. “I would like to sit and talk to you about accessing your lands so we could find the missing children,” Whitecalf told her. McBain invited her into her home, and Whitecalf explained to the couple that oral history indicated the residential school had been on their property and that there could be a graveyard directly under their residence. McBain and Montgomery told Whitecalf they were aware of the possibility and agreed to give the community access to their land and basement.

“We said, ‘Absolutely. We’ve been hearing these damn stories, and we want them clarified,’” Montgomery recalls saying. Whitecalf notified them that their land was now spiritual, sacred grounds. But what did that mean? “We live there,” McBain later told me. “We can’t sell the land—I mean, how do you sell a property like that? I love my house, but I don’t want to live in a graveyard.”

On June 28, the community held a ceremony and feast. McBain and Montgomery were in attendance. In accordance with Cree protocol, the occasion was meant to honour and feed the dead. Four essential items were served: wild-meat soup, berries from the bush, animal fat, and tea. Whitecalf made the bannock. Traditionally, the food is shared and prayed over. Each person sets a small portion of every dish aside, which is then collected and laid in a sacred place or burned. “We welcome the ones that have passed on to come and eat with us,” Whitecalf explained. “So now, every year around the same time, around the twenty-eighth of June, we will have to have a feast in Delmas to feed our children that we haven’t found yet.”

One day that august, about a dozen people, including elders, community members, and three SNC-Lavalin staff, met inside a tipi to pray and offer tobacco to ancestors. The pipe was passed around, and then each person shared a reflection. Many spoke of the indelible trauma of residential schools that had carried on to future generations, materializing in the form of substance addiction, getting caught up in the criminal justice system, perpetrating and being a victim of violence, and premature death. Many Canadians still claim that residential schools are in the past, but federal and provincial governments spend billions every year responding to the symptoms of intergenerational trauma created by their legacy. Much of that money, the TRC found, is spent on crisis intervention related to child welfare, domestic violence, health, and crime.

Noel Moosuk, a sixty-five-year-old elder from Red Pheasant Cree Nation, whose parents attended the Thunderchild school, opened up about how he had suffered as a result. When he was a child, Moosuk later told me, his parents couldn’t care for him and his siblings, and they became alcoholics to cope. “Every time he drank alcohol, he became a monster,” Moosuk says of his father. Moosuk remembers being left without food for days at a time. When his sister was a baby, his siblings hunted a rabbit and made a soup with it to keep her alive. The trauma of physical and sexual abuse Moosuk endured as a child lived on into adulthood. “I was going through different cycles of alcohol abuse, relationship abuse, and I was wondering why these things were things that were happening,” Moosuk says. “It was something that wasn’t talked about, it was so shameful, I was so [ashamed] to be an Indian.” He “killed the pain” by sniffing gas from vehicles. “It’s something that happened over there, to break us up, break the Indian people up to not know who they are,” he says. Moosuk had eight children with two women, both of whom were also caught in cycles of addiction. His children were removed from their home and put in foster care.

Moosuk long ago forgave his parents for what he understood was behaviour that was no fault of their own, but, he says, he still comes across white people who say things like “Get a job” and “Oh, you’re just another drunken Indian.” “But the thing is, they don’t realize what happened to us,” he says. Through the search process, he hopes people will come to understand the enduring damage.

During the search of McBain and Montgomery’s hayfield that weekend, a man named Alvin Baptiste from Red Pheasant Cree Nation smudged people with sage, a traditional form of cleansing, before they entered the grounds. Baptiste is an oskâpêwis, or helper, for spiritual ceremonies—a revered title for someone trained to serve the people. Baptiste smudged with a traditional fan made of brown-and-white eagle feathers.

Five years earlier, Baptiste’s nephew, Colten Boushie, a twenty-two-year-old from Red Pheasant, had been shot and killed by Gerald Stanley, a white farmer, near Biggar, a town in central Saskatchewan. Baptiste had carried the feather fan with him throughout the trial against Stanley, who had been charged with second-degree murder and manslaughter. In 2018, an all-white jury had acquitted Stanley—what Baptiste points to as the systemic racism of the justice system. Baptiste’s mother—Boushie’s grandmother—had attended the Thunderchild residential school for two years, around the time she was five, until the school burned down; Baptiste’s grandparents had also attended. Baptiste says the events, though separated by generations, were connected by a common cause: cultural genocide. He carried the feather fan on the grounds that day and at Boushie’s trial as a symbol of truth and protection. He also carried it to Parliament Hill, where he met Trudeau following the verdict and told him of the country’s failings against Indigenous peoples. “Canada has to do better,” he recalls telling the prime minister.

Once smudged by Baptiste, Dylan Antunes, then a geotechnical engineer with SNC-Lavalin who was overseeing the search, and two colleagues transported their equipment to the grounds they’d surveyed the night prior. They had laid out a grid composed of lines twenty-five centimetres apart. This kind of work is slow, often painstaking, and involves pushing a cart, which emits an electromagnetic pulse into the ground up to a depth of about five metres, across the surveyed lines. Data is received on the cart’s screen that reflects an image of the soil below. In post processing, the data is then stitched together to form a 3D model of the ground. In a previous search of the field, the team had found exposed pieces of the school, and now they were going over an area they understood from the community to be a continuation of the school grounds. Antunes had worked for the company for ten years, primarily on civil infrastructure projects, and this was his first time working to identify unmarked graves. “Never in going through university did I think that this is what I would be doing, but I’m happy that I’m able to,” Antunes told me.

Around noon, Montgomery and McBain arrived to eat lunch with the community in the town hall that Whitecalf had rented for the weekend. McBain and Montgomery wore orange “Every Child Matters” T-shirts, as they had for many related events. Delmas residents rarely, if ever, joined the events despite Whitecalf opening them to the public. Some residents edged by in their trucks, rolling down their windows to get a glimpse; some said they were resentful the hall was being used for such purposes. According to McBain and Montgomery, some Delmas residents turned against them after they agreed to participate in the search process. “You can’t talk to anybody in this community whatsoever,” Montgomery told me. “The ones that I have talked to, other than my friends, they’re all racist. They want to see this whole thing gone.”

After lunch, Whitecalf gathered a few people in a tent to talk. McBain and Montgomery had brought with them a man named Amie Prince, then eighty-three years old, who was raised in Delmas; it was Whitecalf’s first meeting with Prince. In the late 1950s, Prince had worked at the nearby St. Anthony’s Residential School, in Onion Lake, as a sports director. Prince said he had never witnessed any wrongdoing. “You hear a lot of these stories, kids dying, all that kind of stuff. I don’t believe that very much,” Prince told the group. Whitecalf listened calmly; her father had attended the same school. She didn’t tell Prince that, before his passing, her father had shared intimate details of his distressing experience. He had struggled with alcoholism, a result of the trauma he had endured, Whitecalf later told me. Among other known abuses at the school, a teenage girl was allegedly impregnated by one of the Oblate fathers.

Harvey Thunderchild, then a sixty-six-year-old, both of whose parents attended a residential school in the area, told the group that the historic abuses against his people and the legacy of residential schools had left many of his people “dysfunctional.” “I call it a Jekyll and Hyde syndrome,” he said. “You know, without the alcohol, people are calm, great, supportive, loving, caring. But there were issues in there that they haven’t dealt with, and alcohol is a way of distorting their memory,” he said.

“We had a lot of that too in our family,” Prince said. He, too, had been strapped by a nun at school, he said. McBain agreed. “White people were kind of the same. It just isn’t brought up as much. I think there’s just as much family abuse,” she said. “It’s just kept quiet.” In the meeting, I asked Whitecalf and Thunderchild how it felt to listen to Prince and McBain claim similar abuses among white families. “When I hear non-Indigenous people say that we’ve gone through the same thing, to me, I don’t think you have because you weren’t taken away from your family,” Whitecalf said. Maybe they experienced abuse within the home, she said, but “our people, they were taken away from their houses, their homes and put into this building. So that’s the difference, right?” Prince let out a light, awkward chuckle, as if understanding for the first time. “Yes, that could be a hard thing,” he said. “I can see that if you take out small kids like five, six years old away from his mother, you know, it’s not right.” Later, when I asked Whitecalf about the interaction, she said, “It felt like they were trying to downplay it, like, ‘We experienced that too.’ But no, you did not.”

That afternoon, when I walked around town to meet Delmas residents, few wanted to talk. Some said they had no problem with the search. One man, who asked not to be named, told me that he, too, had experienced abuse and strapping at school. He felt the search process was a “money grab” and had trouble understanding why, seventy years later, the past was being exhumed. Most people in the community, he said, felt the same. That summer, people had vandalized or desecrated, in some cases burning to the ground, several churches, many of which were on Indigenous lands, in what was widely considered to be a reaction to the findings of unmarked graves.

The next morning, before Sunday mass, I waited near the Delmas church named Jean Baptiste de la Salle, hoping to talk to attendees. Across the road, people gathered in the tipi for that day’s pipe ceremony. Several Indigenous leaders in Saskatchewan—and countrywide—had called on Catholics to boycott Sunday mass, hoping to pressure the Church to hand over residential school registries and related documents and pay the $25 million it had promised survivors. Meanwhile, a few religious leaders had been reprimanded for publicly downplaying the residential school experience. That July, during several masses at a church in Winnipeg, a Catholic priest named Rhéal Forest said residential school survivors had lied to get settlement money. “If they wanted extra money, for the money that was given to them, they had to lie sometimes,” Forest told parishioners, the Globe and Mail reported. “Lie that they were abused sexually and, oop, another $50,000. It’s kind of hard if you are poor not to lie.” According to the CBC, a priest in Alberta had told parishioners that month the news of unmarked graves was lies.

That day, the Delmas church was quiet; the organ player said many people in town were on holiday. About a dozen locals streamed in, but the pastor, Sebastian Kunnath, who refused an interview, told us not to speak with parishioners.

By early October, several months after the search process in Delmas began, nothing concrete had turned up. McBain and Montgomery’s yard was being searched, and in the town hall, McBain had prepared an elaborate turkey meal, with vegetables she’d picked from her garden, for the crew and community. One morning that week, they invited Whitecalf over for a coffee. “I got something for you,” Montgomery told her as she sat in the kitchen. Decades ago, McBain was riding a horse on the Raven River in Alberta when it kicked up a buffalo skull. She’d since carried it with her everywhere she went. Montgomery had recently decided to fix it up, fastening it to a blue-velvet base, tying colourful ribbons to its horns, painting a circular symbol, and attaching a feather to its forehead. Montgomery gifted the skull to Whitecalf. When she saw it, she started crying. “Do you know what this means? Do you know how sacred this is?” Whitecalf said. She consulted Baptiste and the elders, who said the skull could be hundreds of years old. They told her to face it south and keep it away from negative energy.

When I asked Montgomery and McBain about the gift, they said they’d wanted to show their appreciation to Whitecalf for her patience and kindness. “I am so disappointed with this town, and I think I always have been, and we should never have come here,” Montgomery told me. “We’re getting to know the people. Not the town people, but the native people. You know, like, this is gonna be lifetime friendships with these people.” Still, they had been caught in a state of suspension and uncertainty. No longer able to rent their hayfield or grain bin, they felt they were owed compensation for lost income during the search process. Whitecalf had also approached BATC on their behalf with the proposition that the council purchase their property, regardless of what they found, to create a formal memorial. But all of that was pending. “The wounds keep opening up,” Whitecalf says. “Survivors held it in for so long that nobody talked about it. My dad never talked about it. Now it’s been blown open.”

In June 2022, a year after the search process began, a representative of SNC-Lavalin presented their initial findings to the community. The data did not indicate the possibility of unmarked graves in the area searched. The company, though, expected to continue the search across other areas and in McBain and Montgomery’s basement. Kisha Supernant, an archaeology professor at the University of Alberta, expresses concerns about ground-penetrating radar being interpreted definitively. Instead, she says, it is one of many tools required to locate unmarked burials and is not always appropriate; other methods, including forensics and excavation, can be used in conjunction. Many communities, she adds, focused on the opportunity to use the method when companies offered their services, but it won’t necessarily provide the closure they’re looking for. For instance, the radar wouldn’t detect bodies hidden in walls or in soil that had been disturbed.

Many children who attended the Thunderchild school, and residential schools across the country, never returned home. And while the search continues—in some cases, a century later—for where their bodies may lie, numbers cannot measure the lives stolen and history erased in an incalculable tragedy.

Whitecalf left her role with BATC late last year. Her hope of finding physical signs of the children shrinks. But she has told herself that it doesn’t matter; facing the truth is closure enough. “It’s just that the symbolic part of it was missing. We didn’t acknowledge these kids were there. We just kind of left them there,” she says. “So that’s why we had that feast, and that’s why we will continue to have those feasts until the end of time.”

Spyglass, too, recognizes the challenge of these searches. In the 1990s, she had hope of locating her older brother Reggie’s grave, but all she found was overgrown grass and broken crosses. She couldn’t tell one grave apart from the next.

The National Indian Residential School Crisis Line provides twenty-four-hour toll-free support to former residential school students and their families, at 1-866-925-4419.

The Hope for Wellness Helpline provides twenty-four-hour counselling to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people across Canada, online and at 1-855-242-3310.