It's the recording studio where Bowie made his mark – ok, three marks – Depeche Mode discovered a new direction, and U2 screamed 'Achtung Baby!'. Here's why this 'Big Hall by the Wall' has become a Mecca for some of the best bands of our age, and a look at some of the finest albums they recorded there.

Hansa Tonstudio in Berlin is a legendary studio facility that has seen some of the biggest names in music pass through its doors, and some of the most iconic albums in history recorded there.

Situated close to the old Berlin Wall, the studio opened in the 1960s, specialising in concert performances thanks to it vast Meistersaal (formerly Hansa Studio 2), AKA The Big Hall by the Wall.

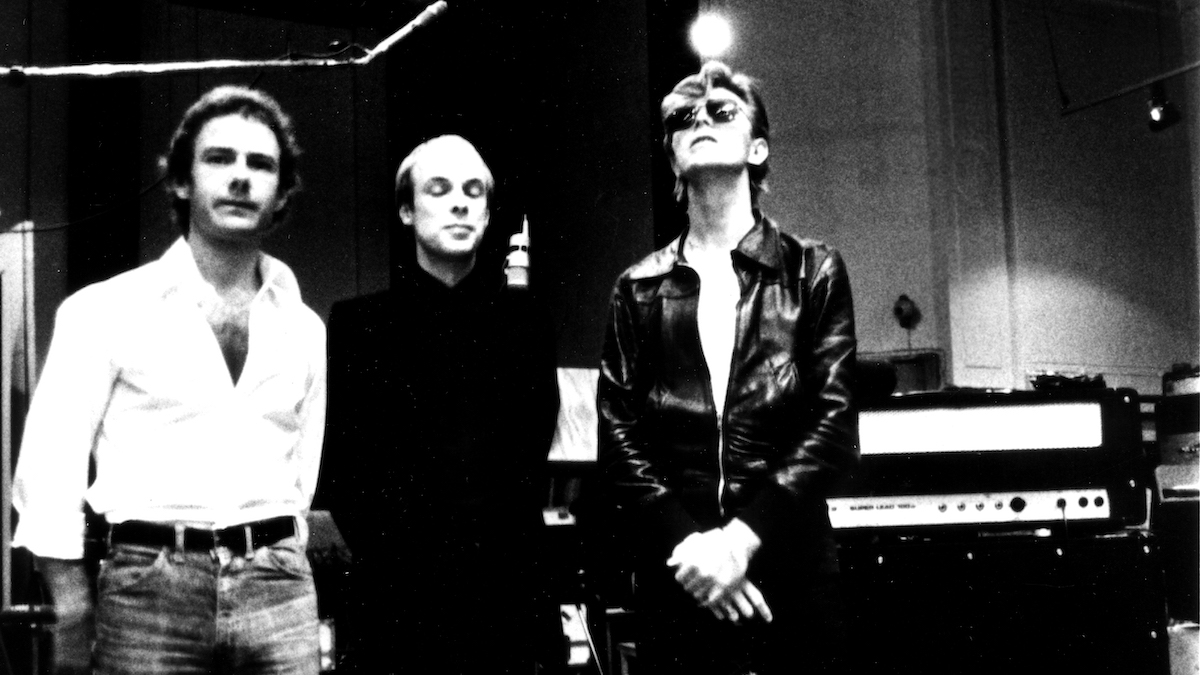

The studio became a favourite hangout for David Bowie and Iggy Pop in the 1970s where the former recorded much of his Berlin Trilogy. Bowie described the building as a studio with a friction that he enjoyed as it acted as a security blanket against its then ominous surroundings – he could famously see the wall and a machine gun turret as he came up with the lyrics for Heroes, for example.

Since then, many have followed in Bowie and Pop's footsteps, hoping to capture some of the hard-to-define 'menance-meets-magic' of the studio.

Here are just six of the artists – including the two that kickstarted the Hansa revolution – and the legendary albums that they recorded there.

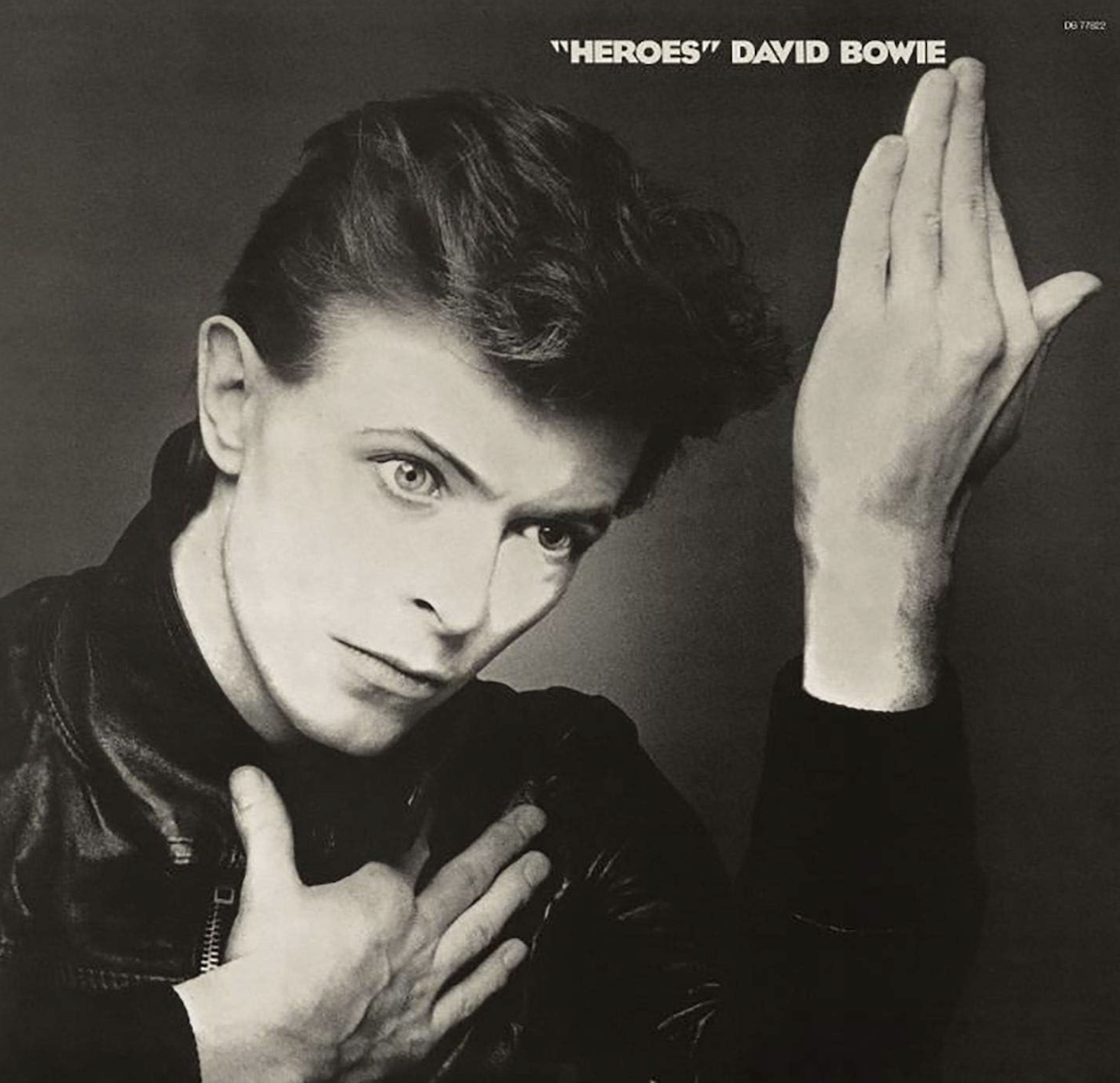

David Bowie – Heroes

We might as well start with the album that put Hansa Tonstudio on the map because, well, it was the album that put Hansa Tonstudio on the map.

That said, Bowie had already recorded much of previous album Low in the studio, along with producer Tony Visconti and Brian Eno, and if we were allowed to include more than one album by an artist on this list, then Low would be it. But we're not! So Heroes gets the Bowie slot, and mostly, we do admit, because of the title track.

It provides a bit of friction, the kind of friction I need. It's not a comfortable place to record.

David Bowie on Hansa

Recording Low was such a positive experience for Bowie, that using Hansa for the follow up was a no brainer. Of the studio, Bowie said: "It provides a bit of friction, the kind of friction I need. It's not a comfortable place to record. You feel it [outside tension] coming in so you develop very strong empathies with the people you are working with. Like a security blanket."

As we'll see with U2 below, the best bands go into studios armed with nothing but the confidence they have that they are going to make a great album, and that was the case with much of Heroes.

Bowie had his regular band – Carlos Alomar on guitar, Dennis Davis on drums and George Murray on bass – on hand to record backing tracks, along with Eno and his EMS Synthi AKS suitcase synth.

To say that the recording of the album was fast is an understatement. Chord structures would be thrown around, songs made up on the spot and lyrics too.

"I never knew the complete melody until I'd finished the song and played the whole thing back," Bowie told The Observer in 1977.

The process worked though, with both Eno and Bowie writing and most of the backing tracks completed in days, while the bulk of the recording process was completed in around a month.

Inevitably, as good as Heroes the album turned out to be, it was always going to be overshadowed by its title track, a piece of music that has come to be the track synonymous with the late singer, and one that all lazy journalists turn to in moments where they don't quite know how to finish off a story. Here it is.

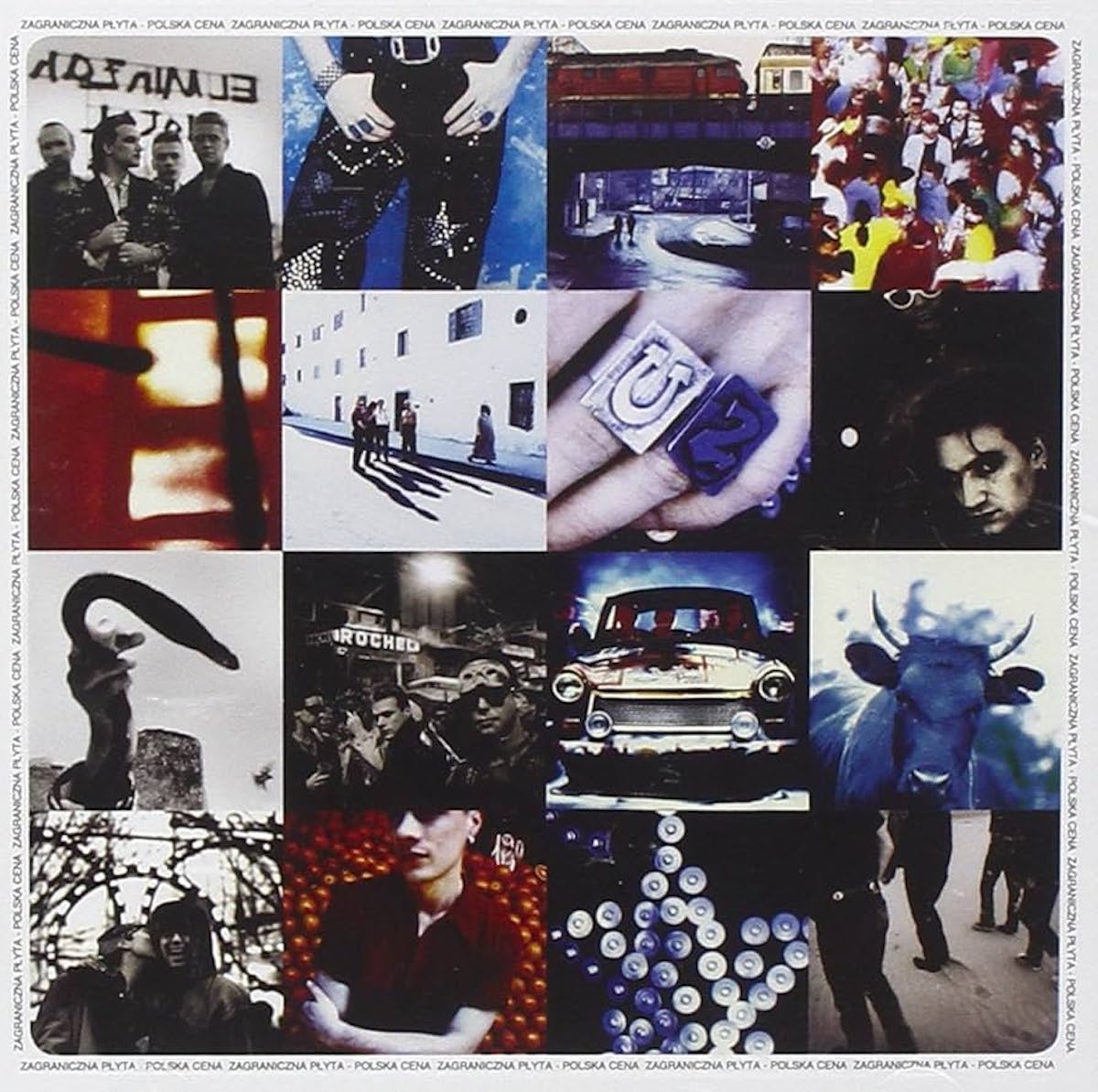

U2 – Achtung Baby

In the late 1980s, U2 were at something of a crossroads, or so they thought. Having done the U2 thing and conquered the world with The Unforgettable Fire and The Joshua Tree, but not so much with Rattle and Hum, they needed a new direction. And with the Berlin Wall starting to crumble, they did what so many bands did before them and since, and headed to Hansa for inspiration.

The rest of us might call it 'making it up as you go along', but then the rest of us haven't recorded The Joshua Tree

With regular contribs Brian Eno And Daniel Lanois coming along for the Trabant ride, along with super-engineer Flood, it should have been easy. Eno was certainly no stranger to Hansa, having recorded the odd hit there with Bowie, and even with the studio not in that great a shape (thanks in part to the surrounding city chaos), he and the band were in a good place to start recording.

The trouble was, what would they record?

At the time, U2 tended to write on the spot in the studio, not going in with any firm song ideas. The rest of us might call it, 'making it up as you go along', but then the rest of us haven't recorded The Joshua Tree, so what do we know?

This time, however, all the band had in their locker were conflicting ideas. Edge had clearly been hanging around at too many Berlin techno clubs and wanted electronic beats (which can't have pleased drummer Larry Mullen Jr). Mullen and bassist Adam Clayton were opting for more traditional rock, while lead singer Bono was erring with Edge.

Berlin was difficult. I had quite a strong feel where I thought it should go. Bono was with me.

Edge

“Berlin was difficult," Edge would tell Rolling Stone. "I had quite a strong feel where I thought it should go. Bono was with me. Adam and Larry were a little unsure. It took time for them to see how they fit into this.”

After much to-ing and fro-ing at Hansa, the band eventually struck gold with the track One (which to these ears says that Mullen and Clayton won the first round).

“It was one of those hairs-on-the-back-of-your-neck moments," Edge says in the From The Sky Down documentary about the arrival of One. "It was such a pivotal moment. We’d been going through this hard time and nothing seemed to be going right. And suddenly, we were presented with this gift.”

It would be the spark that led to Achtung Baby although, in truth, most of the recording of the rest of the album took place in Dublin and over an extended year long period following the Hansa session.

We’d been going through this hard time and nothing seemed to be going right. And suddenly, we were presented with this gift.

The Edge

Still, we're including Achtung Baby as it turned out to be exactly the crossover album U2 had hoped for, and also exactly the right concept to see them crash into the 1990s in what we called at the time, a 'multimedia' way, and continue their world takeover. Yes only one track ended up being recorded at Hansa, but it proved to be the pivotal one. (And we're writing this feature so we make the rules, ok?).

It also gives us a great excuse to conclude with this clip in of U2 playing opening Achtung track Zoo Station at The Sphere earlier this year.

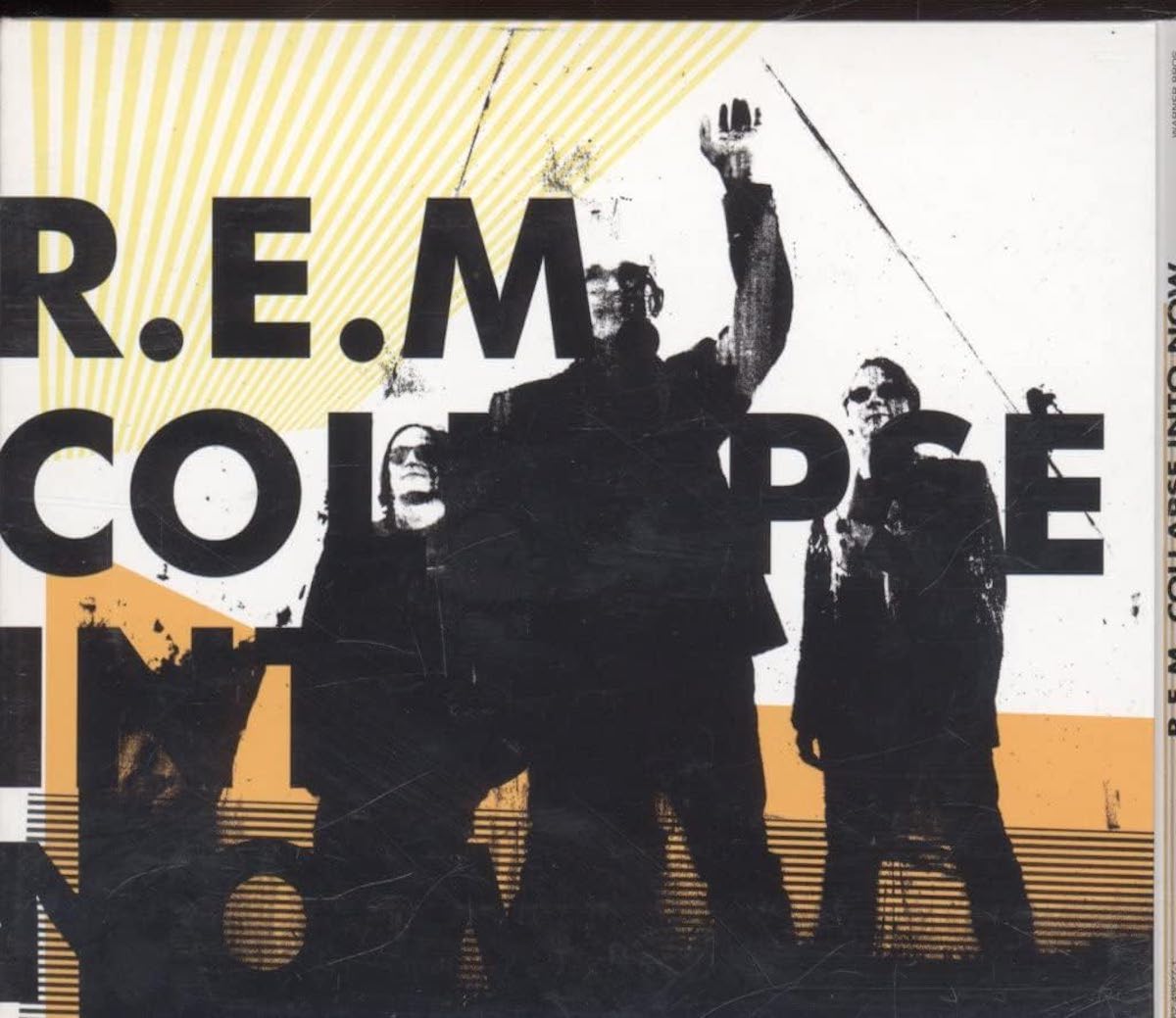

REM – Collapse Into Now

The 15th and final R.E.M. album was actually recorded in four different studios but the most songs – as many as eight – were recorded at Hansa Studios in 2010.

The band – Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Michael Stipe – knew that they were splitting up while they recorded the record, having discussed ending R.E.M. as far back as 2008, but they kept that to themselves during the album's recording.

I wanted to present an idea of what an album could be in the age of YouTube and the Internet

Michael Stipe

The band were also very much aware of how the music business was unfolding around them, with streaming and Youtube becoming dominant, leading them to believe that albums like this would become rare.

“The idea was to present a 21st-century version of an album," Stipe told Interview. "What does an album mean in the year 2011, especially to generations of people for whom the word album is an archaic term? I wanted to present an idea of what an album could be in the age of YouTube and the Internet.”

It meant that different videos were shot for each track rather than the album being promoted by touring, meaning the final recording at Hansa would be a proper full-stop. Many of the tracks were also filmed while played live at Hansa including this one.

The Hansa videos – and there are a good half dozen on YouTube – are all the more important because they would be the last time R.E.M. would play together.

"The only time we got really poignant was when we were working in Berlin, and they have a beautiful room there, Meister Halle, where we recorded seven or eight songs," Mills said in an interview with the A.V. Club. "We knew that was probably the last time we would ever play together as R.E.M. That was a pretty fraught day."

We knew that was probably the last time we would ever play together as R.E.M. That was a pretty fraught day.

Mike Mills

Collapse Into Now ended up being the band's poorest selling album, and had mixed reviews on release, with some describing it as disjointed. However, it deserves reappraisal all these years later, especially knowing that the band knew it was their last, and feels more like a band delivering nods to various parts of their history as a last and glorious final lap.

R.E.M. didn't officially announce their disbandment until September 2011, six months after the album came out, although Stipe says there were several clues on the album, including him waving goodbye on the cover.

"There's a good chance that we'll never play together again," Peter Buck told the Guardian in 2011 after the band announced their intentions to quit. "And that'll make me feel sad, except for the fact that I played [those songs] a lot for a long time. I can't imagine anything in this moment that would cause us to use the name R.E.M. and play songs again."

Depeche Mode – Black Celebration

Black Celebration was the third in Depeche Mode's very own Berlin Trilogy of albums. They had recorded parts of 1982's Construction Time Again and follow up Some Great Reward in 1984 at Hansa, and Black Celebration was the final instalment in 1986. The album would see the band finally reach the end of their journey towards a darker sound, a million miles away from the synth pop from their youth.

Early Depeche were your clean cut, older brothers. These were the uncles you avoided at family gatherings.

Where earlier Mode songs might have been aimed at a teen audience with themes of love and new romance, Black Celebration was about death, danger, stalking and sex. Early Depeche were your clean cut, older brothers. These were the uncles you avoided at family gatherings. If there are love songs on the album – and there are – they are mixed with dead flies on windscreens.

Which isn't to say that this is a bleak listen. Black Celebration is one of the band's finest and fullest recordings. Hansa helped in its dark, oppressed and twisted feel, but Martin Gore's songwriting and engineer/producer Gareth Jones and Daniel Miller's direction helped take the sound from the sublime and atmospheric…

to full on and sinister…

… to Epic.

The Black Celebration studio sessions ended up being fraught, but as is so often the case, tension in the studio can result in a band's finest work and Black Celebration – as well as being the album that heralded in the all new Mode – is one of Depeche's greatest albums.

And when you have Songs of Faith and Devotion, Violator and Memento Mori in your locker, that is some praise.

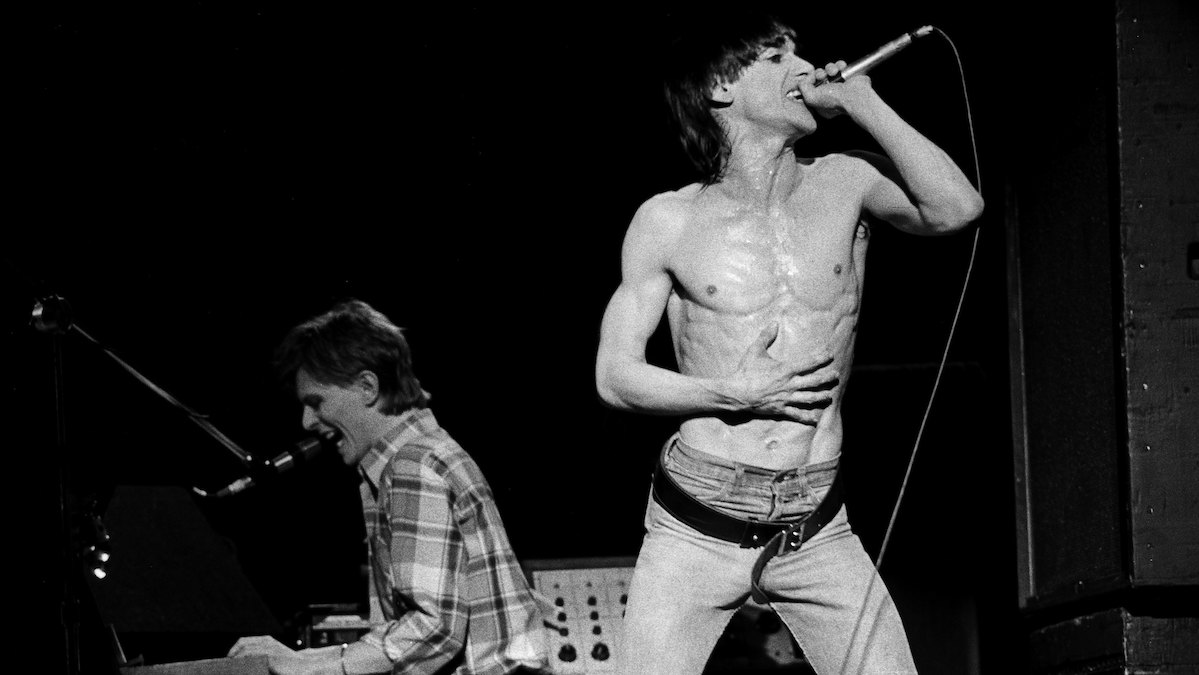

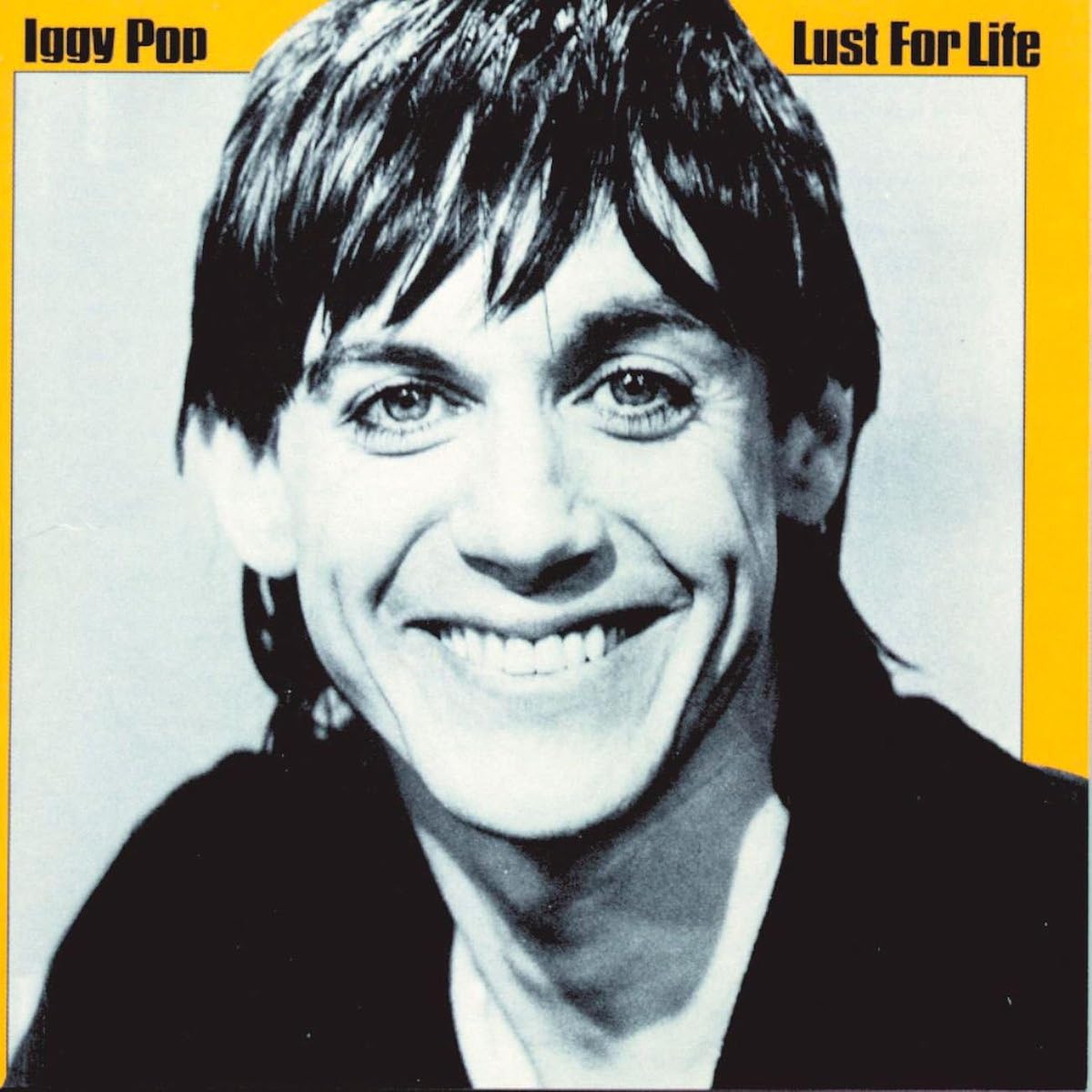

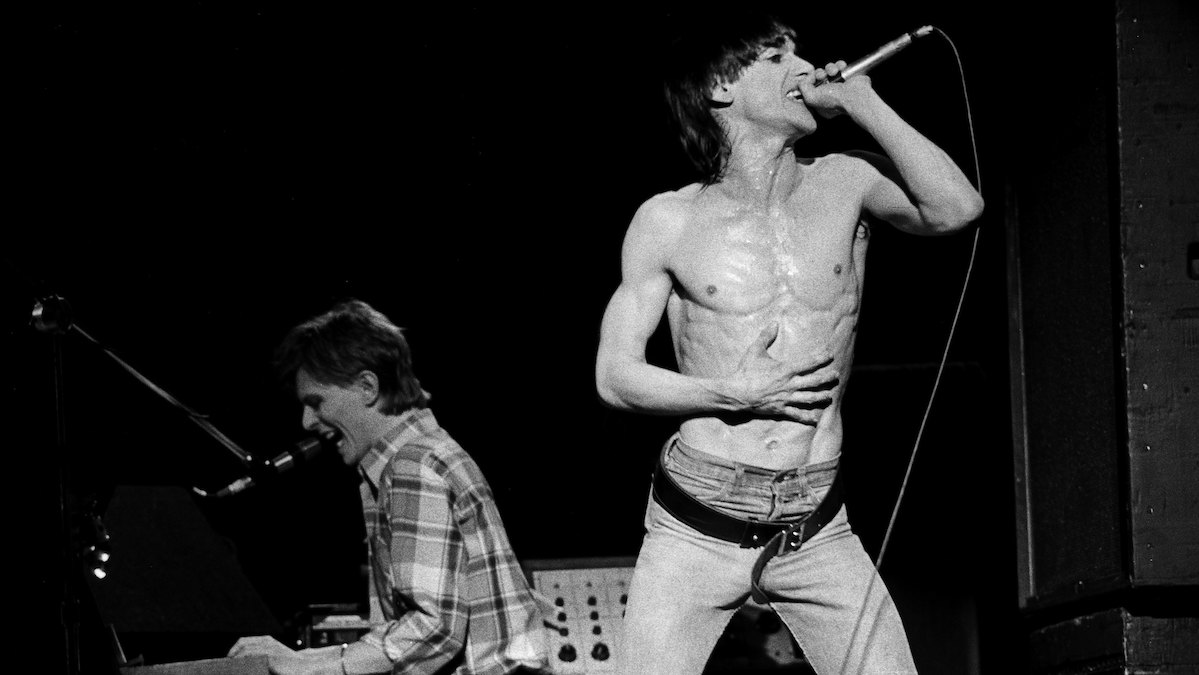

Iggy Pop – Lust For Life

The fact that Iggy Pop and David Bowie lived in the same apartment block in Berlin and that Kraftwerk used to come and visit (as they confirmed in the lyrics to Trans-Europe Express) should have BBC sit-com writers reaching for their pens. Yes, Berlin was the most creative of cities in the late 70s, and between the four of them, they ended up producing some of the albums that have defined our times.

Iggy Pop and David Bowie were enjoying a particularly creative period. Bowie had just completed Low in the city (with some of it recorded at Hansa) and had also worked with Pop on the album, The Idiot, Iggy's debut album that he produced after his previous band The Stooges had broken up.

Bowie had rather dominated their work together on The Idiot, and Pop wanted to have a bigger say on Lust For Life, but did use Bowie's arrangements, particularly on the standout title track which is credited to both.

Lust For Life was a big success – the title track and The Passenger still pop up on many a soundtrack to this day – so much so that Bowie hinted that the two of them would produce a third album together, although that wouldn't happen until the duo reconvened in the mid 80s.

What the album does demonstrate was how creative Bowie was in Berlin in this period, actually considering two trilogies in total and mostly within the hallowed space of Hansa.

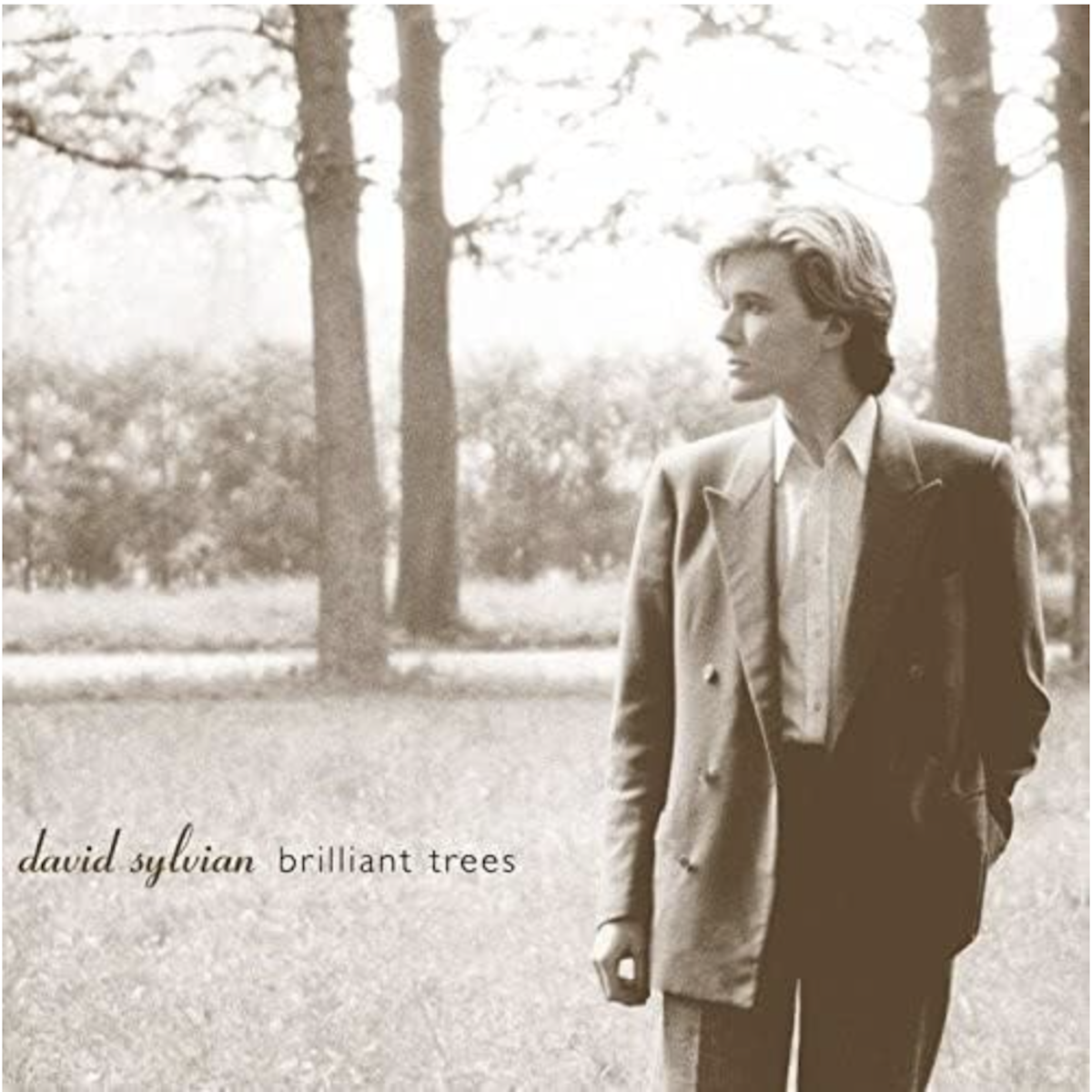

David Sylvian – Brilliant Trees

The story of the late 70s and early 80s band Japan and its successes, failures, split, reunion and split again is one for a very large feature, another time. At the centre of it all, though, has been the enigmatic front man David Sylvian.

At the end of the band's first chapter in late 1982, Sylvian was desperate to remove himself from the pretty boy pop image of his former band and calve his solo way. Along with producer Steve Nye, they eventually decamped to Hansa in 1983 to start putting together the first step in that journey.

Sylvian's songs touched on the great thinkers and artists of our times and wove in all sorts of genres in an album that was at one time far removed from anything Japan had done, but as forward-thinking as that band's incredible Tin Drum LP.

Sylvian couldn't quite leave his past behind, enlisting former Japan bandmates Steve Jansen (his brother) and keyboard player Richard Barbieri for the project. He also couldn't resist writing the odd hit record for it.

While Brilliant Trees would certainly go onto confuse many Japan fans with its ambient jazz leanings and chin-stroking spirituality, it did go on to shift over 100,000 copies. This gave Sylvian the confidence to plough his own way which has led to some incredible work, including follow up albums Gone To Earth and Secrets Of The Beehive.

Sylvian's escape from synth-pop to solo art-house, can easily be compared to that of Talk Talk/Mark Hollis – indeed, there can be no higher praise – and the journey (for want of any other expression) began at Hansa.