Having practically grown up on Sri Lankan food, thanks to a parent from the country, makes me somewhat picky when it comes to how spicy my pol sambol is or how soft yet crisp hoppers (appams) need to be. And yet, Sri Lanka manages to surprise me time and again with its food — its freshness, dedication to detail, and sheer variety.

What does an authentic, going-back-to-the-roots food experience feel like in Sri lanka? I am at the Cinnamon Lodge Habarana, a resort in Habarana, a small town that is around four hours (about 180 kilometres) from Colombo. Here, the focus, when it comes to food, is on farm to fork: locally grown, fresh produce, cooked, served and enjoyed with just the right blend of tradition and modern comfort.

The Lodge sprawls across 27 acres, a portion of which is devoted to organic farming. A walk around the property, which is a man-made biodiversity habitat, brings me to a working farm: capsicum, corn, aubergine, vanilla, ginger and beans, all neatly labelled, grow alongside lemon, pomegranate, dragon fruit, star fruit and passion fruit. And of course mangoes of all kinds — different varieties are available more or less around the year, says the lodge’s general manager, Murfad Shariff. Butterflies flit in and out, on their way to the butterfly garden that shares space with crops. A climate-controlled greenhouse supplies lettuce and gherkins.

Many of the vegetables and fruits used in the kitchens are grown in-house, says Murfad, and the farm supplies both the 138-room Cinnamon Lodge, as well as the property next door, the 108-room Habarana Village by Cinnamon. Both 42-year-old properties are owned by Sri Lankan hospitality major, Cinnamon Hotels & Resorts (a constituent of the Lankan conglomerate, John Keels Holdings), which owns 11 hotels/resorts in Sri Lanka and four in the Maldives.

Despite being a dry zone, Anuradhapura district, where Habarana is located, is one of the major paddy-growing areas of the country. Murfad, who manages both the Lodge and the Village, tells us that the Lodge also cultivates paddy on its in-house farm. The entire plantation is provided for by a composting unit, and a sewage treatment plant ensures that even in the dry season, there is enough water for plants.

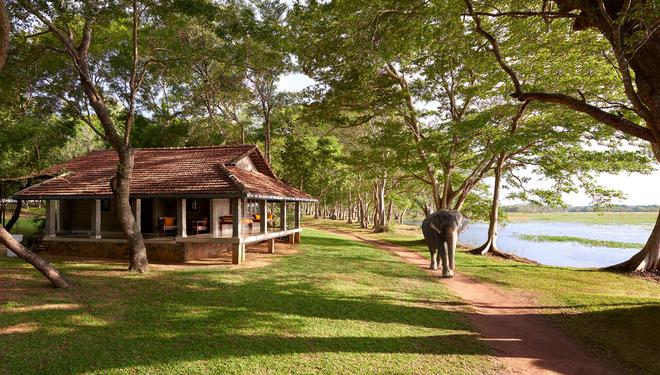

The resort is bordered by a lake, on the other side of which are agricultural fields melding into the forest.

It’s true what they say about fresh air: it whets the appetite. The Lodge has two restaurants and two bars, and several location dining experiences, ranging from the romantic and the adventurous, to the just something different: dining on the jetty, treetop dining, dining on an island and dining at a hut, Seilama, are some of the options.

We have dinner at Seilama: a mud-floor structure with a thatched roof (called a Chena hut) with wooden tables and benches laid out with terracotta crockery. Outside, on the grass, sits a large earthen structure, a replica of a Vee Bissa, a traditional paddy storage apparatus, a nod to the district’s primary livelihood.

Though some of the food may look familiar, especially to Indians from the southern states, when it comes to the influence of coconut and the predominance of rice, Sri Lankan cuisine is uniquely its own, drawing not just from its local landscape but also the ethnic diversity of its people and its one-time colonists, the Dutch and Portuguese.

The traditional experience of course, means no cutlery. Banana leaves are laid out on clay plates (or woven baskets). We start with soup, rasam-like, known as Thambun hodi, served with warm, crusty dara poranu paan, firewood oven-baked bread. Chef Sampath tells us this is what farmers’ wives traditionally served their menfolk after they came back from a hard day’s labour. If it was meant to revive their strength, it must have amply served its purpose — the bite of intense pepper towards the end will shake you out of any drowsy feelings the mellow atmosphere may bring about.

On the menu are pol (coconut) rotis, and idiyappams (string hoppers) with a touch of bright colour — not just the white and red rice flour ones, but also those made from butterfly pea flour. There are also elawalu rotis (stuffed vegetable) and stuffed chicken rotis, which make for a nice snack. With this, we have Sri Lankan dal curry, polos ambula or baby jackfruit curry, Jaffna prawn curry, a vegetable stew and chicken curry.

The rice is Dunthel bath, a flavoured, fragrant yellow rice, along with red rice, darker than usual, made of kurula thuda, a traditional red rice variety, which Chef Sampath tells us is chock-full of fibre. Accompaniments include three sambols: pol (cocunut-y), katta (spicy) and seeni (sugary), along with gotukola, or pennywort that is cooked poriyal style.

We end with wattalapam, which Chef Sampath describes as the Sri Lankan caramel custard, topped with a cube of jaggery: refreshing, and not as sweet as its European cousin.

Warm and replete, we watch the somewhat-unseasonal rain spatter the grass outside. Monkeys, audaciously swinging on the massive banyan tree’s roots earlier in the day, have scuttled away. The walk back to the room may be damp, but waiting just inside, there is an armchair, a misty window and cup of Ceylon tea.

The writer was in Sri Lanka at the invitation of Sri Lankan Airlines.