A little over seven years ago, in February 2017, Ashley Graham was getting dressed in a furry cropped jacket and sweater dress to make history. She would be the first-ever curve model to walk Michael Kors's runway at New York Fashion Week.

“[I’m used to being] the only curved girl—I’m just excited that every designer and every magazine is going in the right direction," Graham told Vogue at the time. The Fall 2017 season seemed to her like a turning point in the long fight to make fashion more size-inclusive at every level. Beyond her debut Kors show, plus-size models were booking covers and catwalks. Brands were expanding their size ranges. "It’s not just one designer. It’s not just one model," Graham said. "It’s the wave of the future." It appeared that a one-size-fits-all mentality was finally starting to shift. Seven years later, the tides have turned.

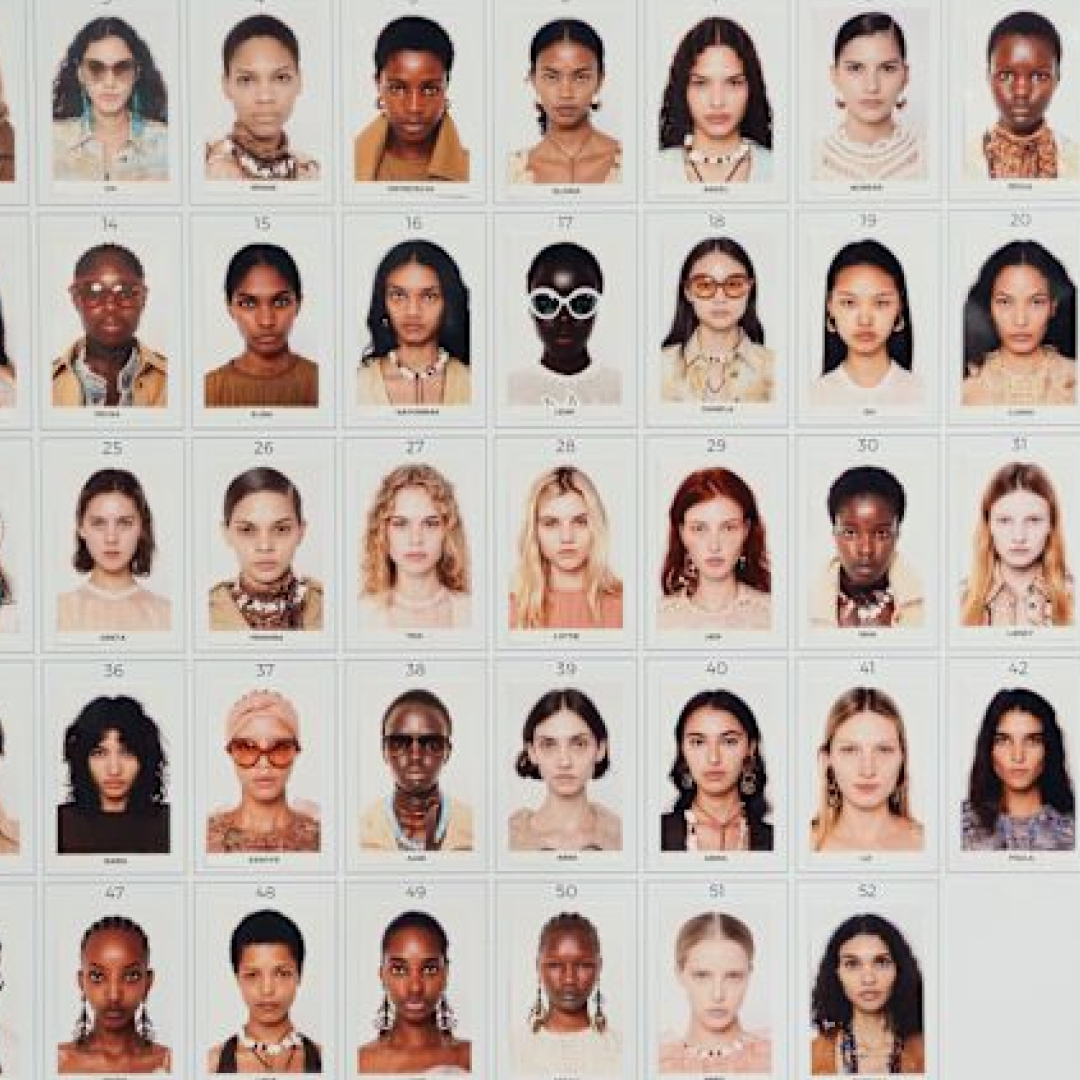

Earlier this week, Vogue Business released its semi-annual size inclusivity study, which measures the body types represented in model castings across the Spring 2025 runways held in New York, London, Milan, and Paris. The trade publication found that only 0.8 percent of 8,763 looks shown at 208 shows and presentations were plus-size. (Plus size equating to a US size 14 and above.) The previous season's castings for plus-size models also landed at sub-one percent. Castings for mid-size models (that's sizes US 6–12) increased between the seasons—if you can really call it that—from a 3.7 percent to 4.3 percent "improvement." The other 94.9 percent were straight-size.

Sadly, these numbers weren't necessarily a shock to more than a dozen fashion editors, publicists, stylists, and buyers I spoke with after the study was released. Attendees had headed into the season wanting to see themselves, or at least a mix of bodies, in the best hot pants and naked dresses the runways had to offer. But they all retreated to their group chats, and eventually my DMs, with the same conclusion: the rise of get-thin-fast drugs (like Ozempic, initially intended to treat diabetes) and TikTok's thirst for "how to be skinny" content overshadowed the season.

"I definitely expected there to be less body diversity given the proliferation of GLP-1s," says The Love List writer Jessica Graves. "Only a few designers like Grace Ling and Christian Siriano stood out to me for making an actual commitment to body diverse models."

Shuffling from show to show at New York Fashion Week's Spring 2025 season, I noticed the backslide myself: model after model was a size US 0 or 2, with hips jutting out of a crochet dress or ribs I could count from my seat in the front row. By the end of the week, and moving on to London, Milan, and Paris, an appearance by a curve model like Jill Kortleve or Alva Claire felt like a shadow of Graham's 2017 musings: they were often the only one in the room.

"It would be easy to blame semaglutide drugs like Ozempic or Wegovy for all of the distressingly thin models on the runways last season (so many!), but I’d argue that [these drugs] have simply made it easier to indulge in our non-stop quest for thinness," Marie Claire beauty director Hannah Baxter tells me. They've created a culture where it's once again permissible to get thin at all costs—and fashion rewards it.

Seeing the same frail bodies over and over again affected Baxter's close industry friends and herself: "All I had to do was glance at the recent Paris shows to feel like I’m in 2003, 14 again, and concerned that my thighs are growing too big."

As designers cut down their size-inclusive castings, they're not only reshaping our understanding of who belongs on a runway. They're also narrowing the pool of women who they produce clothing for beyond fashion week.

Take the red carpet, for example. Ariel Tunnell, a VIP stylist, dresses clients whose sizes range from a 2 to a 24. She tells me she's noticed a decline in looks for mid- and plus-size women since the pandemic, as brands cut costs by making smaller samples. That means her clients don't have as many options to choose from. "This season, in particular, was very disappointing. There are just so few runway looks for mid-size and plus clients," she says. "Aside from [Christian] Siriano, very few designers cater to real women’s bodies. Unfortunately, it really limits options to ready-to-wear and custom."

I heard the same refrain from regional clothing buyers and personal stylists: They're seeing a narrower vision on the runway and fewer options to share with their clients and customers.

While some brands argue that size-inclusivity is too expensive for their business to sustain, that doesn't seem to be the case at Copenhagen Fashion Week, where even the most nascent brands on the official calendar consistently cast models of all body types. Of course, that market has a set of minimum standards requiring participating brands to be inclusive.

It's heartbreaking to realize that body inclusivity now seems to have been treated as just another trend—one that’s fading just as quickly as it appeared.

Regressing to a "thin is in" casting directive can also have harmful health consequences, notes Ruthie Friedlander, co-founder of The Chain, a nonprofit providing peer-to-peer support for women in fashion and entertainment who are struggling with or recovering from eating disorders. For perspective, eating disorders have been on the rise in the US since 2020, per data from NEDA (National Eating Disorders Association). When fashion imagery touts a single, largely unattainable body type as the gold standard, women on and off the runway feel they need to conform to the detriment of their well-being. "The fashion industry has a significant influence on these pressures, and the shift away from size representation is not just disappointing—it’s dangerous and life-threatening," Friedlander says.

"Seeing this season’s shows," she adds, "it’s heartbreaking to realize that body inclusivity now seems to have been treated as just another trend—one that’s fading just as quickly as it appeared."

Most of the publicists, editors, and general clotheshorses I spoke to for this story agreed they wanted to see more diverse bodies back on the runway (and, frankly, everywhere). Stepping outside my own bubble of forward-thinking fashion people, I've seen some insiders online defend skinny-girls-only casting by saying not every brand is meant to be for everyone. But really, who does or doesn't wear a brand should only come down to aesthetic taste—not dress or pants size.