Growing up in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata), where food is something akin to religion, and in a house presided over by my mother who was a fabulous cook, my memories of great food and grand meals are prodigious. Yet, when I sat down to write this piece, a single memory leapt to my mind — a memory from so long ago that it should have faded by now. Only, it hasn’t. Even today, on somnolent Sunday afternoons, I wistfully recollect our day trips to Barasat on the outskirts of Kolkata, where we had a bagaanbari (literally, a house with a garden), and where the caretaker would cook lunch for us visitors. The food wasn’t anything fancy, but sitting al fresco and eating off chipped, mismatched plates while the birds kept up a drowsy monotone of cooing in the trees above, everything tasted heavenly.

The caretaker-cum-gardener- cum-cook’s name was Ponchu. He must have had a more civilised name, or bhalo naam, as we say in Bangla. But he was universally known as Ponchu. I called him Ponchu da. In winter, and also in autumn and spring when the weather is pleasant in Kolkata, we went to the bagaanbari at least one Sunday every month, accompanied by either the extended family or some of my parents’ close friends.

En route ‘shingara’ and ‘jileepi’

Barasat in the 1970s was not the bustling Kolkata suburb it is today. In fact, it was quite bucolic, and every time we went there, I felt as though we were journeying to some far-off land. Once you left the confines of the metropolis, the road became magical, flanked on either side by shimmering waterbodies and lush green vegetation.

The foodie experience began en route. Around 9.30 a.m., we would stop for breakfast at a large mishtanno bhandar (sweet shop). Leaning against our Ambassador cars, we ate freshly fried, thin-crust shingara (samosa) stuffed with cauliflower and potato, khasta kochuri (flaky kachoris), and delectably crispy jileepi (jalebi) and aumriti (imarti), passing around the newspaper packets that held these goodies, our fingers greasy with ghee and our palates alight with joy.

You’d think that after such a heavy repast, there would certainly be no elevenses and lunch would be an abstemious affair. But no one was watching their cholesterol back in those days. And I suspect Ponchu da would have been seriously baffled and hurt if anyone was.

For he kept the food coming almost from the moment we reached the bagaanbari. There would be several rounds of tea and tidbits to go with it — daler bora (lentil fritters), machher dim bhaja (fish roe fritters), beguni (brinjal fritters), pneyaji (onion fritters)… Sometimes tea was eschewed for drinks that the adults had brought along, while I glugged from a bottle of Fanta.

The one-storeyed baari (house) part of the bagaan was pretty rudimentary, but the grounds had an air of plenitude — laden with trees like coconut, mango, jackfruit, wood apple and banana, a largish vegetable patch bursting with seasonal veggies, and a pond which, Ponchu da claimed, had lots of fish, though I rarely caught a glimpse of them through the layer of kochuripana (water hyacinth) that floated on it. Much of the food cooked on those memorable Sundays came from the produce of that land, and maybe that’s what accounted for its intensely fresh and satisfying flavour.

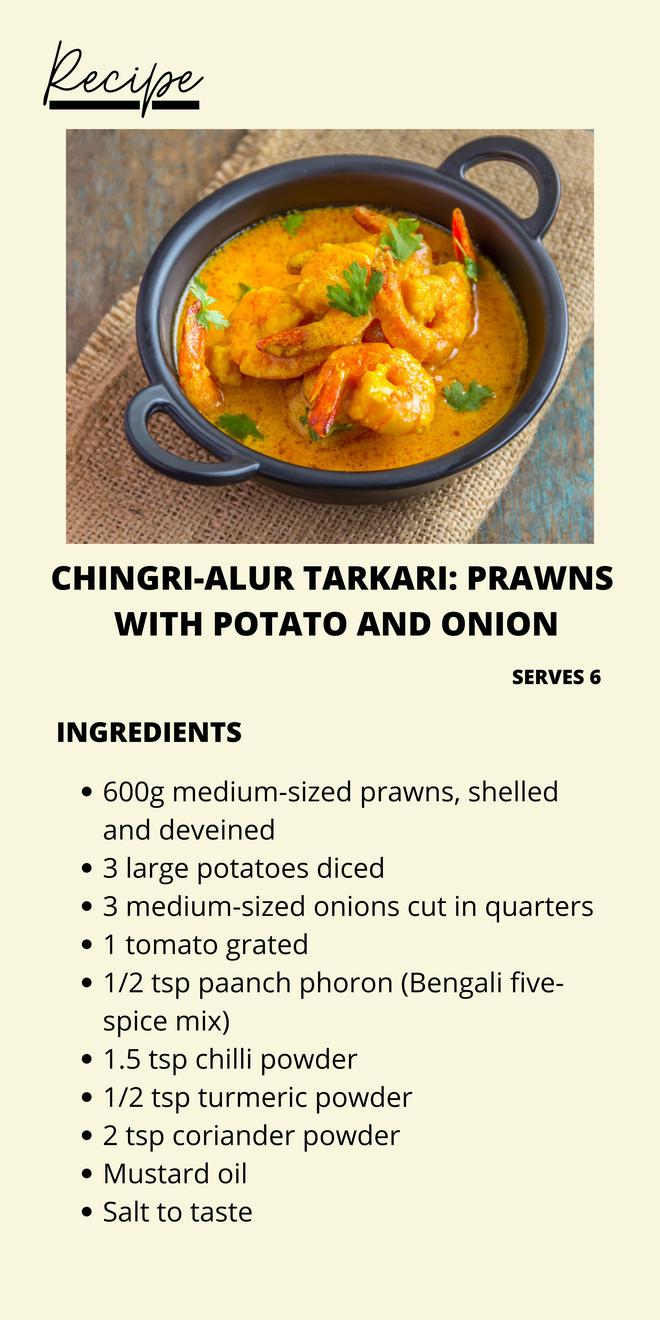

As a cook, Ponchu da’s repertoire was fairly limited. Our late lunch usually had a standard menu: smoking hot rice with fragrant, locally sourced ghee, narkel diye chholar dal (Bengal gram dal cooked with diced coconut), with maybe some fried topshe fish on the side, phulkopi-alu-koraishutir dalna (potato-cauliflower curry with peas), chingri-alur tarkari (prawns with potatoes), rui maccher kaalia (a rich curry with rohu fish) and a chicken or a mutton or a crab curry, followed by tomato chutney and mishti doi.

Sitting in the dappled shade of the winter sun, we ate this elaborate meal with slow relish. Every dish had a hearty, somewhat rustic flavour, a little high on spice, and higher still in its ability to speak straight to the soul. One that I particularly liked was the chingri-alur tarkari, a simple peasant-style preparation seasoned with paanch phoron and cooked with prawns, diced potatoes and onions. My mother had asked Ponchu da for its recipe. He had obliged, but had also added sadly that she would never be able to replicate its taste because, like all the food he cooked for us, this dish too was done on wood fire. “It’s the wood fire that makes everything healthy and tasty,” he said.

Maybe there was some truth in that. Or maybe it was the sylvan setting, the sparkling air and the soothing bird call that gave those meals the elevated, soulful dimension they seemed to have.

Or maybe it was just some magic wrought by Ponchu da, chef and multitasker extraordinaire, whom we never saw again after the bagaanbari was sold a few years later.

The writer is a journalist and author with an obsessive interest in food.