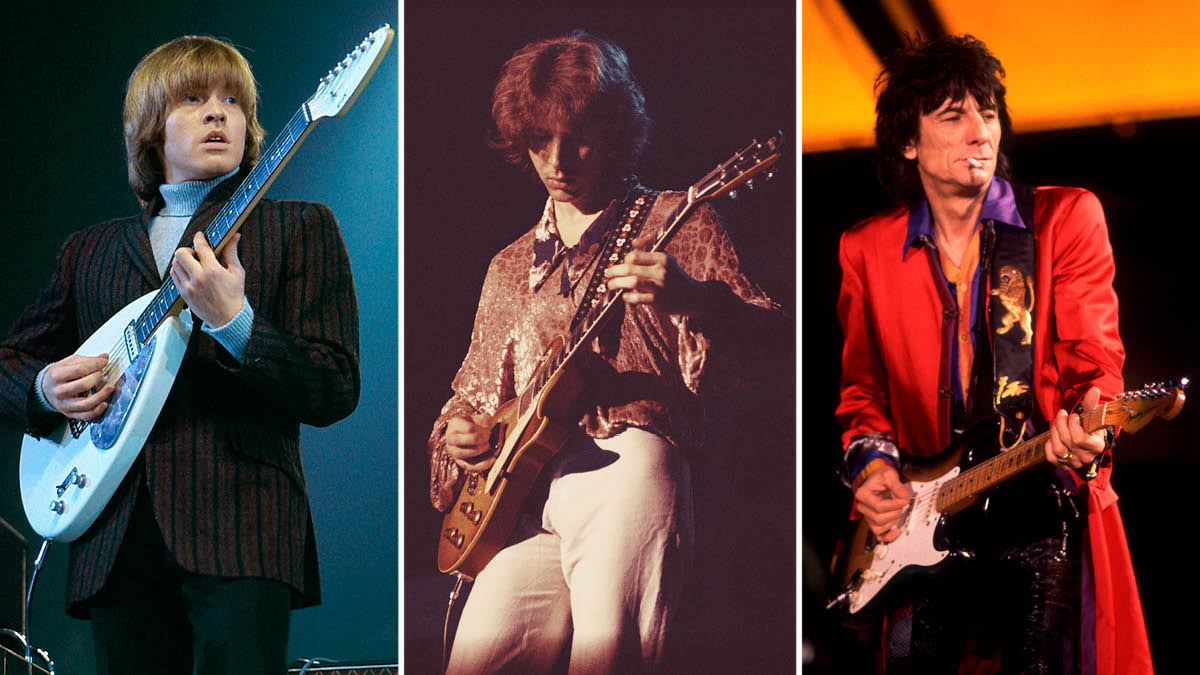

Jones, Taylor and Wood… It sounds more like the name of a law firm than the surnames of the three phenomenal guitarists who have served alongside Keith Richards during the Rolling Stones’ six-decade-plus career.

Now that they’ve released Hackney Diamonds, their first album of original material since 2005’s A Bigger Bang, it’s an ideal time to reflect on the contributions that Brian Jones, Mick Taylor and Ronnie Wood have made to the evolution, vitality and uncanny longevity of the Stones.

Each guitarist’s tenure with the group – seven years for Jones, five for Taylor and an amazing 48 for Wood – serves to define and delineate three key phases in the Stones’ stellar career. Here’s how it all happened.

1962-1969, Brian Jones: The rock star as tragic hero

It’s not just that Brian Jones founded and named the Rolling Stones in 1962 – giving birth to one of the most important groups in all of rock history. That alone secures his place of high honor in the rock pantheon. But Jones also was an archetype and icon in so many other ways.

One of the first young, white Britons to play blues-style slide guitar, his role in bringing the venerable, African-American blues idiom (and blues guitar particularly) to the forefront of rock makes him the godfather of a tradition that includes British guitar greats like Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Peter Green, Mick Taylor, Alvin Lee and so many others.

With his impeccably coiffed blond mane, boldly extravagant fashion sense and dazzling arsenal of ultra-flash guitars, Jones was one of the 1960s’ most influential guitar heroes. He consorted with Swingin’ London’s glamorous models and actresses, hung out with Bob Dylan and journeyed to Morocco in 1967 to smoke hash and pioneer the world music scene.

The Pied Piper of the psychedelic explosion, Jones adorned the Stones’ mid-’60s oeuvre with a rainbow orchestra of harpsichords, flutes, sitars, dulcimers and Mellotrons. In this, he played a key role in forging the baroque pop/chamber pop subgenre that’s still flourishing today. He introduced the Jimi Hendrix Experience to the audience for the trio’s American debut at the seminal Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. He was always in the vanguard.

The dark side of all this was that Jones was deeply unhappy in his fame – conflicted, ambivalent and embittered. When he lost creative control of the Stones to Mick Jagger and Keith Richards in the mid-’60s, he went into a prolonged tailspin, abusing dope and booze in ever-increasing amounts until he ended up dead in a swimming pool at age 27 in July 1969.

In so doing, he became a charter member of the infamous “27 Club” – musical legends who died too soon and whose ranks also include Robert Johnson, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse. Even in death, Jones rolled with the best.

“Brian was an impressive musician,” Keith Richards told me in 1997. “Very promising. He was a sax player as well, to start with. He was dedicated to playing in those early days. I’ll tell you what screwed Brian up: it was fame. Something snapped in him the minute that came.”

Brian was an impressive musician... He was dedicated to playing in those early days. I’ll tell you what screwed Brian up: it was fame

Keith Richards

Having already played with London blues kingpin Alexis Korner and preceding Eric Clapton in a group called the Roosters, Jones was definitely heavier business than Jagger and Richards when the three first teamed up in 1962. He was the kingpin, but the blues made a brotherhood of the three young musicians. In those hardscrabble days before fame tore them apart, Brian and Keith would spend hours huddled together with their guitars in a dingy, unheated flat they shared with Jagger in London’s Edith Grove.

They’d riff along to the precious collection of African-American blues and R&B records the three aficionados had amassed. From this emerged the propulsive, tight-yet-fluid two-guitar style that Keith Richards has ever since called “an ancient form of weaving.”

“When Brian and I started playing together,” Keef told me, “we were listening to a lot of Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters – the two-guitar thing. The weaving. We did it so much. Which is the way you have to do it. So we knew both parts. You get it to where you get it really flash, and you suddenly switch. The one playing the rhythm picks up the lead, and vice versa.”

One of the great rhythmic paradigms of rock guitar history, the sound Jones and Richards made together was first committed to tape on March 11, 1963. The Stones’ debut demo session was engineered at London’s IBC Studios by soon to be legendary producer/engineer Glyn Johns (the Beatles, Who, Led Zeppelin, Clapton, etc.). It was immediately clear to Johns who was in charge at that point.

Brian was pretty much the leader. He was certainly the spokesman for the group to me

Glyn Johns

“Brian was pretty much the leader,” Johns told early Jones biographer Mandy Aftel. “He was certainly the spokesman for the group to me. This was their first recording session and Brian was very much concerned about the sounds that I would produce on tape. He had an exact rhythm and blues sound he wanted – the Jimmy Reed type sound, which was virtually unheard of.”

That murky, mysterious sonic miasma was what made early Stones singles like Tell Me and Time Is on My Side so utterly fascinating when they were first released in 1964. Tone was Jones’ obsession. His guitar contribution to the early Stones oeuvre breaks down into two main areas. For one, there’s his raw, raunchy, open-tuned slide playing on tracks like I’m a King Bee, Mona (I Need You Baby), Grown Up Wrong and Little Red Rooster.

Secondly, there’s Jones’ co-equal role with Richards in forging the gritty, two-guitar grind of the Stones’ mid-’60s sound. With equal aplomb, Jones could crank out a hooky lead riff on The Last Time or pound out a pumping rhythm on tracks like Satisfaction or 19th Nervous Breakdown. He took a slide to a Rickenbacker 360 12-string electric to create the Middle-Eastern flavored riff on Mother’s Little Helper, doubling Richards, who also played slide on an electric 12-string.

Jones’ tone-mania led him to acquire new guitars as voraciously as he collected new clothes and new girlfriends. He did much to popularize the Gibson Firebird, which was still quite a new and daring instrument at the time, first introduced in 1963.

But the guitars with which Jones is most closely associated are his two white, teardrop-shaped Vox MK III prototypes, handmade for him by Vox design engineer Mick Bennett. The lute-like body shape was very innovative, and the MK III became a garage band classic as soon as the first production models hit the street in 1964.

“Brian would hop from instrument to instrument,” Richards told me in 2002. “He was always searching for another sound. As a musician, he was very versatile. He’d be just as happy playing the marimba or bells as he was guitar. Sometimes it was, ‘Oh, make up your mind what sound you’re going to have, Brian!’ ’cause he’d keep changing guitars. He wasn’t one of those guys who say, ‘Right, here’s my axe.’ Brian had so many.”

Despite Jones’ growing alienation from the Stones, he was deeply enthusiastic about the return to basics represented by Mick and Keith’s 1968 song, Jumpin’ Jack Flash. “We’ve been in the studio all morning and we’re going back to rock and roll!,” Jones excitedly told a girlfriend. “They got this Jumpin’ Jack Flash and it’s really great.”

Indeed, a new era was dawning for the Stones – a return to the primordial blues, R&B, rock ’n’ roll roots they’d first dug into with Jones. It’s nice to think that Jones lived to contribute to the glorious, bluesy rebirth that is the Stones’ 1968 masterpiece, Beggars Banquet. His plaintive slide playing on No Expectations brings the story full circle, returning to the guitar style that had launched Jones’ career.

To this day, Brian Jones' DNA is all over the storied group

The Stones’ longtime producer Jimmy Miller said, “As a musician [Brian] should be remembered for the brilliant bottleneck country guitar work on Beggars Banquet and for his interpretation of the blues played honestly, as a white man.”

Sadly debilitated by drugs and booze, Jones hung on long enough to strum an autoharp on Keith Richards’ song You’ve Got the Silver on Let It Bleed. Shortly thereafter, in June 1969, Jagger, Richards and Watts fired Jones from the Rolling Stones.

Less than a month later, he was dead. His passing marked the end of one of the greatest eras in rock music and the career of the Rolling Stones. To this day, his DNA is all over the storied group.

1969-1974, Mick Taylor: Golden boy of the Stones’ golden age

The four-year period that spans Beggars Banquet in 1968 and Exile on Main St. in 1972 is, for many, the absolute zenith of the Stones’ career. Sure, they did amazing work both before and after, but the ’68-’72 period was one of those magical moments when pop culture, the stars and the Stones were all aligned.

A new decade was dawning. Crawling from the wreckage of the ’60s, John Lennon was revisiting his roots in ’50s rock ’n’ roll. Bob Dylan had gone into an introspectively folksy acoustic mode. The Stones had ditched the dandelions and rainbows of the psychedelic era for something more earthy and grounded.

Meanwhile a new breed of blues-based virtuoso guitarists like Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Mike Bloomfield, Peter Green, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and many others had placed amped-up, single-note pentatonic riffing at the forefront of rock music.

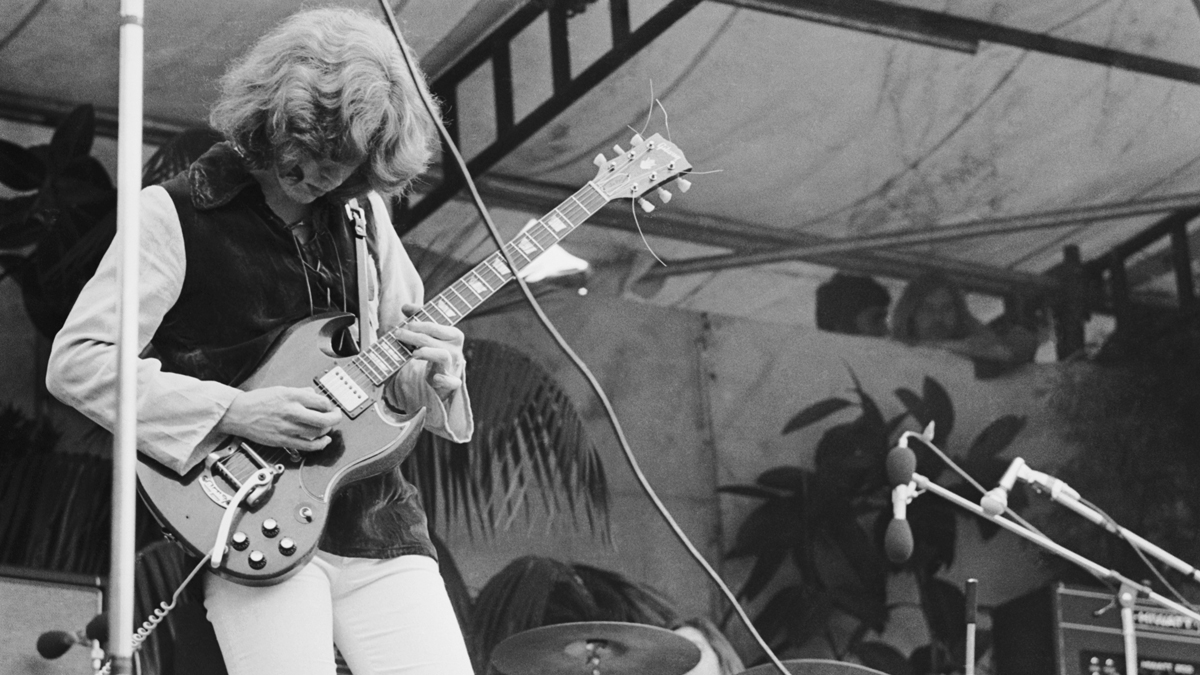

All of which made Mick Taylor a perfect choice to replace Jones. At just 17 years old, Taylor had succeeded Clapton and Green as the guitarist in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers – a band that had set the gold standard for British blues guitar mastery. Mayall himself called Jagger to recommend Taylor. As did Ian Stewart, the erstwhile, and brilliant, Rolling Stones pianist who’d been Jones’ oldest and closest comrade within the Stones’ circle.

Taylor made his recorded debut with the Rolling Stones on their July 1969 single Honky Tonk Women. One of the greatest rock records of all time, it announces the arrival of a triumphant period for the Rolling Stones, with Keef rock solid in his recently discovered five-string open-G tuning and Taylor blazing away in six-string standard.

But Taylor – a teetotaling vegetarian when he joined the Rolling Stones – never seemed to fit in completely. Several years younger than the other Stones, Taylor would always seem a bit fresh-faced and naive amidst the notorious rock libertines known at the time as “Satan’s Jesters.”

This mismatched lifestyle stood in stark contrast to the phenomenal musical chemistry going down during this period. Music critic Robert Palmer Jr. summed up the situation quite succinctly:

“Taylor is the most accomplished musician who ever served as a Stone. A blues guitarist with a jazzman’s flair for melodic invention, Taylor was never a rock and roller and never a showman.”

Taylor made his album debut with the Stones on their 1969 album, Let It Bleed, trading licks with Keef on Live with Me. He also overdubbed slide guitar on Country Honk, taking up the bottleneck role that Brian Jones had abdicated, and slipping into the Stones lineup as Jones slipped away. By the time the Stones released their next album, Sticky Fingers, in 1971, Taylor had been fully integrated into the lineup.

He and Richards had forged a tight, punchy, two-guitar rhythmic and melodic approach. The way their guitars dart and twine around one another in the intro to Brown Sugar is sheer six-string poetry. Taylor’s spontaneously improvised, Latin-tinged, Gibson ES-345 archtop solo on the outro of Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’ is another landmark Stones guitar moment.

Taylor also notably played a 1961 Gibson SG and 1959 Les Paul with the Stones. He shared Jones’ affection for Gibson Firebirds as well. The Stones were in the midst of an Ampeg amp endorsement when they convened to record their double-disc masterpiece, Exile on Main St.

That album’s opening track, Rocks Off is another two-guitar Stones classic, replete with a balls-out outro solo from Taylor. He’s a vital part of an album that routinely tops Best Rock Record of All Time lists.

The live side of Taylor’s work with the Stones was generously captured on disc – the seminal Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out – and on film–the Maysles Brothers’ landmark 1970 documentary, Gimme Shelter, and 1974’s Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones. Post Exile, he played on two more Stones studio albums, Goat’s Head Soup and It’s Only Rock ’n Roll. And then he was gone – his departure taking his fellow Stones and the band’s fans somewhat by surprise.

“Mick’s a lovely player,” Richards told me. “I never understood why he left. He’s always been a bit restless and a little uneasy inside his skin. But I enjoyed playing with him. I learned a lot from him. We learned a lot about guitar playing from each other. Because he’s another great weaver. His tone and his touch and his melodic ideas wow me. I’d just hoped he would have gone on to bigger and better things than he did. I thought it was an impetuous move.”

Publicly, Taylor explained his abrupt departure by saying he’d become bored musically and that the enormous entity that is the Rolling Stones had taken his life over. What went unmentioned at the time was that the clean-cut guitarist had also fallen under the spell of Dame Heroin and wanted to get out before flirtation turned to thralldom.

Tensions had also arisen between Taylor and Richards, as Taylor’s songwriting role within the Stones grew while Keef sank deeper into his own heroin-addicted lethargy. Taylor and Jagger co-wrote Moonlight Mile and Sway from Sticky Fingers and Till the Next Goodbye and Time Waits for No One on It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll, released in 1974. Taylor was especially fond of his guitar solo on the latter track.

“I think it’s probably the best thing I ever did with the Rolling Stones,” he told GW’s Damian Fanelli in 2012.

Taylor had expected to receive co-writing credit on those tracks. When he didn’t, the animosity grew. In the middle of a party at rock entrepreneur Robert Stigwood’s home, Taylor informed Jagger that he no longer wished to be a Rolling Stone.

Of Keith Richards’ three co-guitarists in the Rolling Stones, Taylor’s tenure was the briefest, but, in many regards, the most well-remembered today. While Taylor would go on to do much good work after leaving the group, he’d never again achieve the level of fame he’d attained in the Stones. Much like his predecessor, Brian Jones, he was essentially too much of a blues purist to ride rock ’n’ roll’s roller coaster of fame.

1975-present, Ronnie Wood: Keeper of the flame

Numerous legendary and respected guitarists were in the running to take Mick Taylor’s place in the Stones. The list includes Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Steve Marriott, Rory Gallagher, Shuggie Otis, Harvey Mandel and Chris Spedding, among others. Many were called, as the saying goes, but only one was chosen.

There are so many reasons Ronnie Wood has proved to be a perfect match for Keith Richards and the Rolling Stones. He sprang from the same scene as the Stones, playing guitar with a mid-’60s R&B outfit called the Birds (who have absolutely nothing to do with the Byrds, the American band behind Mr. Tambourine Man and Chestnut Mare) and also attending some of the Stones’ earliest gigs at London clubs like the Crawdaddy. So he knew where the Stones were coming from, literally.

“I was their biggest fan when I joined them,” Wood told me in 1997. “And I still am, while being in the band.”

Also, unlike both of his predecessors, Wood was no stranger to rock stardom when he first joined the Stones in 1975. Though originally a guitarist, the ever-versatile Wood served as bassist in the Jeff Beck Group, performing on the landmark Beck albums Truth and Beck-Ola and jamming with Jimi Hendrix at the Scene club in New York. From there, Wood had gone on to play guitar with ’70s hitmakers Faces, fronted by former Jeff Beck Group singer Rod Stewart.

So he’d experienced enough of rock ’n’ roll’s fast-lane craziness not to get spooked by the whole thing. In fact, he seemed rather to enjoy it – perhaps a little too much at times. But while he has struggled with addiction issues, Wood has shown much the same uncanny ability to bounce back from oblivion as his Rolling Stones co-guitarist.

Wood and Richards have developed the kind of intuitive “Vulcan mind meld” approach to guitar arrangement that Keef enjoyed with Jones and Taylor

Wood made his recording debut with the Stones playing guitar on three tracks from their 1976 album Black and Blue – the funk-inflected Hey Negrita the straight-out rocker Crazy Mama and a cover of the Earl Donaldson reggae classic Cherry Oh Baby (later a hit for UB40).

The Stones were moving in new stylistic directions in the mid-’70s. Wood’s performance on Black and Blue proved that he could go there with them. Musically, he’s the perfect utility man – able to insert himself gracefully into any musical context, as he’s consistently demonstrated over the course of 48 years, 11 studio albums, seven live albums and countless live shows with the Rolling Stones.

Much like Brian Jones, Wood is a musical chameleon, albeit in a different way. Jones was a multi-instrumentalist; Wood has, for the most part, expressed his own tonal adventurousness within the guitar realm.

He inherited the Jones/Taylor role of slide guitarist in the Stones, but has expanded on that tonal palette to include lap steel, pedal steel, Dobro and B-benders. A man of many guitars, he’s also versatile and supple on six-string electrics and acoustics in standard tuning. Over the years, he and Richards have developed the kind of intuitive “Vulcan mind meld” approach to guitar arrangement that Keef enjoyed with Jones and Taylor.

“We just sit down and hack things out,” Wood explained in my ’97 interview. “The great thing about offstage, when Keith and I are together, is that we talk, more or less, through our guitars. We never say, ‘You do this and I’ll do that. I’ll play the riff and you come in and out.’ We weave.”

This approach works very well for Richards too, as he told me in a 1997 interview. “I’m impressed by everything Ronnie does. He’s a great guy to play with. A great guy to hang with. You get two guitars and Ronnie Wood in a room and the rest of the world will go by.”

Wood’s role within the Rolling Stones is twofold, really. On the one hand, he acts as custodian of the guitar legacy laid down by Jones and Taylor during the Stones’ first dozen or so years. As concerts have come to overshadow albums in the current music industry, this role has been especially crucial – particularly since the departure of the band’s original bassist Bill Wyman and the 2021 passing of Charlie Watts.

You get two guitars and Ronnie Wood in a room and the rest of the world will go by

Keith Richards

“Brian Jones had a very distinctive rhythmic input into the band, which I try and recreate on things like You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” Wood told me. “And on songs like All Down the Line, I try and echo what Mick Taylor did as well. I think that’s part of the song – the melody line he does as a solo.”

But equally important is the role that Wood has played in moving the Stones into the modern era. His guitar work is essential to iconic tracks like Miss You, Beast of Burden and Start Me Up, bringing the Rolling Stones through the disco era and into a new mode of tough, stripped-down contemporary rock classicism that has been their modus operandi ever since – a key ingredient in their phenomenal longevity.

Latter-day albums like Voodoo Lounge, Steel Wheels and Bridges to Babylon represent a third golden era for the Stones – a triumphant victory lap in which Wood has played no small role.

It’s a big nut to crack, that Jagger/Richards songwriting team. I suppose it’s like trying to get a song in with Lennon and McCartney

Ronnie Wood

He has also manned the bass for tracks like Emotional Rescue and Dance Part 1. The latter song, from 1980’s Emotional Rescue, was also one of Wood’s first co-writing credits with the Stones.

Credit for songwriting input had been a deal breaker for Mick Taylor, but through patience, perseverance and bonhomie, Wood has been able to gain much-deserved recognition.

“I spent many years being credited for ‘inspiration’,” he laughed as he told me. “Let’s put it that way. But I didn’t mind waiting. It’s a big nut to crack, that Jagger/Richards songwriting team. I suppose it’s like trying to get a song in with Lennon and McCartney. I like to leave the songwriting for the Stones to Mick and Keith, ’cause they are the institution. But whenever there’s a gap, I’ll gladly offer to fill it. You don’t get anywhere if you don’t try.”

The Rolling Stones’ previous studio album was 2016’s Blue and Lonesome, a down-and-dirty, live-in-the-studio rendition of 12-bar blues classics from legends like Willie Dixon, Little Walter and Jimmy Reed. It’s a loving homage to the music that first inspired the Stones at their inception.

Well more than half a century down the line, the record – and Ronnie Wood’s contribution therein – might well have made the heart of the Stones’ founder Brian Jones swell with pride. The same could be said for Angry, the first single from Hackney Diamonds, which proves that the Stones’ perpetual riff engine is still in fine form.