The role that sampling has played in democratising music making can’t be understated. Since the technology became widely available in the late-’80s and early-’90s it has offered a workaround for independent and cash-strapped musicians to achieve things that would previously have required access to high-end studios and expensive session musicians.

Need a string section? Sample it from an old disco record. Looking for drums? Why not slice that convenient drum break. As technology has progressed, things have only gotten more convenient, to the point that it’s conceivable to create a Hollywood-quality orchestral score entirely from your laptop with access to the right sampled instruments.

Free music samples: download loops, hits and multis from SampleRadar

One area where this democratising has been particularly pronounced has been vocals. Traditionally the cornerstone of rock and pop, and a key element of dance genres like house, a vocal line is particularly hard to capture without access to the right talent, tech and know-how. But by sampling a pre-existing recording, or accessing a commercially available sample pack, solo producers can get their hands on the raw materials without ever having to plug in a mic.

As much as it should be celebrated, sampling can also be contentious. Every few months, it seems some dinosaur of rock production will pop up to vent about how modern music is inadequate because it’s all based on loops and samples, and nobody is a real musician anymore.

While that’s an obviously tiresome opinion and easily dismissed, it is true that there is such a thing as ‘lazy’ sampling. We’ll name no names, but undoubtedly anyone reading this can think of a track or two they’ve heard over the years where a pop, dance or hip-hop artist has built a hit around a sample very obviously lifted from a well-known source with very little creative flair.

When it’s done well, the vocal ‘flip’ is an art form all in itself

When it’s done well, however, the vocal ‘flip’ is an art form all in itself. Whether that involves putting a recognisable source in a new context, or completely deconstructing and reworking a sound so that even the best internet sleuths can’t figure out your source material, creative use of a vocal can turn an otherwise pedestrian track into a classic.

It’s this process we’re focusing on this month; the journey of finding, capturing and reconstructing vocal samples, and how creative processing and effects can make them your own.

In 2024, there are a multitude of ways to access sampled material, each of which offers benefits and drawbacks. Before we dive into the process of working with samples, let’s explore these options, and the best ways to make use of them.

Before digital technology diversified the formats we use to consume music, the vast majority of sampling was done by hooking up to the audio output of a vinyl turntable

Before digital technology diversified the formats we use to consume music, and before the rise of commercially available sample libraries, the vast majority of sampling was done by hooking up to the audio output of a vinyl turntable. For some purists, sampling from vinyl remains the only way to go, although in reality it’s by far the least convenient route in 2024. Not only does the process require access to a turntable and amplifier, but also a stash of physical records to work from.

There are, however, a multitude of reasons why sampling from vinyl remains appealing. For one, the way that vinyl affects the frequency content of audio and applies a distinctive crackle – particularly when working with older, worn records – is a highly desirable and often emulated effect. What’s more, there’s a pleasingly tactile nature to capturing audio from a record, whereby the sound can be manually sped up, slowed down, scratched or reversed.

For many ‘crate diggers’, the inherent inconvenience of hunting for vinyl treasure, as opposed to simply hopping onto a search engine, is a significant part of the appeal. Whereas Google or YouTube may turn up exactly what you’re looking for with a few well thought out search prompts, hunting for vinyl – particularly through bargain bin and second hand sources – and then trawling your finds for workable acapellas, breaks and stand-out moments, can lead a producer down unexpected and creative rabbit holes.

Sampling from a source such as YouTube is far easier than a hardware source too, particularly via audio routing tools such as SoundFlower or Audio Hack

As much as it’s easy to be negative about the internet (both as a sample source and just as a malevolent presence in general), it’s also impossible to deny the depth and flexibility it offers. From rare tracks and live performances to iconic speeches, fan-made cover versions to old-documentary footage, there’s no end to the vocal inspiration that can be found by embarking on a search for something unique. For example, sample libraries like Loopcloud are a one-stop shop for samples when you’re looking to make a complete track in a frictionless way.

Sampling from a source such as YouTube is far easier than a hardware source too, particularly via audio routing tools such as SoundFlower or Audio Hack. The quality of online sources can, admittedly, be variable – and almost universally lower quality than that of vinyl or a professional sample library – but still usable.

While YouTube sampling can be a tricky area when it comes to legality and clearing samples, an alternative is to trawl the multitude of Creative Commons sources and sample swapping forums that offer ready access to royalty free or easy-to-licence source material.

Professionally-produced, commercial sample packs have never been more varied, convenient and easy-to-access. Whether it’s complex, multi-sampled instruments that can replicate full choirs or operatic vocals, or genre-themed loops and one-shots, there are sample packs out there to suit pretty much any vocal need. Tools like Splice and Loopcloud make it incredibly easy to audition sounds within your DAW too, often allowing the user to automatically fit project tempo and key even before committing to a purchase.

A key benefit to using sample packs is the legality – royalty-free sounds mean no need to clear a sample before release, and no risk of being hit by a costly bill later on. The flip side, however, is that a commercial sample is far more likely to appear in another producer’s work, and could run the risk of making your tracks feel less unique. Still, it’s not just the sample itself that makes a track stand out, but how it’s used – even well-worn material can sound fresh and unique in the right hands.

Whatever route you take, modern tech has made it far easier to extract a vocal, even without a ‘clean’ acapella.

Pitch shifting, formant shifting and vocoding

Pitch-shifting is a key method for vocal sampling. Whether subtly shifting the key of an entire loop or adjusting individual words or syllables to a specific scale, unless you’re working with bespoke source material, it’s likely you’ll need to do a little shifting at some point to make your samples fit your track.

In these cases, subtle or transparent pitch shifting is often desirable. Dedicated tools like Celemony, Melodyne or Antares Auto-Tune are great for this, although most modern DAWs are capable of flexible, convincing audio editing so you can get by without a more expensive pitch-correction plugin.

Extreme, over-the-top pitch shifting is also a common, ear-catching way to make vocal hooks stand out. Overtly pitched-down vocals have become arguably overused in certain realms, but the approach of radically altering a vocal sample’s pitch to create new textures and melodies is still one with lots of creative mileage.

Burial’s Archangel is an evergreen example of this done well, in which the publicity-shy London producer takes slices of an acapella lifted from R&B singer Ray J’s One Wish and pitch shifts individual syllables to create the track’s emotive melody. There are lots more contemporary examples of the same technique too, particularly among the work of the likes of Fred again…, Daphni or Jamie XX.

A similar effect often mistaken for pitch shifting is formant-shifting, though there are big differences between the two. ‘Pitch’ is determined by a fundamental frequency and a set of related harmonics. If you change both of these together, the whole pitch of an instrument changes, like when you sing the difference between a C and a G, say. However, if you lined up eight different singers and asked each one to sing the same pitch, they wouldn’t all sound alike.

The reason for this is, in part, due to the physiology of each singer. Imagine just the throat size and shape of each one – this variable alone is enough to produce hugely different characteristics, even if pitch was unified across each singer. These differences can be warped or manipulated by formant shifting. The most common application is to shift the perceived gender of a vocal performance – making male vocals sound more female, by raising the formants, or making female vocals sound more male by dropping them.

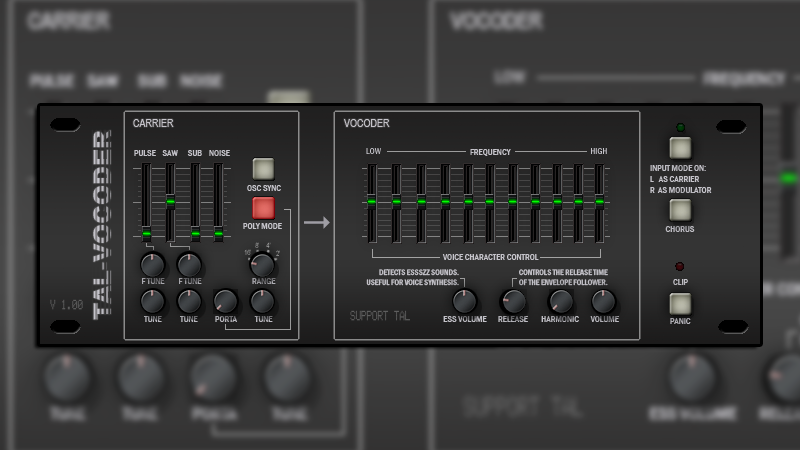

Vocoders

Vocoders offer specialised synthesis engines that allow for a modulator signal, often a human voice, to be used to modulate a carrier signal, typically a synth. This lets us retain the character of the modulator signal, but manipulate the pitch of the carrier using a MIDI input or keyboard. This instantly gives you the advantage of being able to extend the harmonic language of your track as, rather than being tied to the original pitch of the vocal phrase you’re using, you can play any notes you like.

This means that you could, for example, double the bassline of your track with the vocal, or create a brand new part with as much harmonic complexity as you like. The synthesiser engines of most vocoders allow for plenty of flexibility, so you can either create something with a ‘clear voice’ which sounds fairly like the original part you’re processing in timbral terms, or go for something much more robotic to create a more biting, sinister sound.

As vocoders are synths, they also benefit from letting you bring in tricks you’d associate with ‘regular’ synths too, such as pitch-bend and glide effects. One of your vocoder’s key parameters is its number of ‘bands’; these refer to the number of filtered slices the incoming audio is broken down into, so for clearer voices, increase the number of bands. For more distorted ones, vice versa.

While traditional vocoders were typically played live using a mic and keyboard, modern plugin versions can usually be used like insert effects or via sidechain routing that allows the effect to be applied using pre-recorded audio or samples.

Using vocals to create textures

Vocals shouldn’t be restricted to adding the lead hook in a track, vocal sampling can be great for atmospheric purposes too

While vocal sampling is commonly used to provide hooks, melodies or toplines for tracks, there are plenty of more atmospheric or experimental ways to work with vocals too. Adding something recognisable as a voice can be a great way to add a natural or humanised feel to a track, but this doesn’t necessarily mean using a full sung vocal line.

Sometimes just peppering a beat with ghost note-style fragments of human voice, even low in the mix, can turn a synthetic-sounding track into something more emotive. With a little processing too, it’s possible to turn raw vocal samples into textures more akin to ambient pads or atmospheric backdrops.

Let’s take a look at three approaches…

Rather than looping a full phrase or even a single word, try creating quick loops of smaller chunks of a vocal, such as a single beat syllable, an ad lib or breath sound. Applying filtering, and modulation of things like amplitude and pan position can turn these simplistic loops into something almost pad-like.

Extreme reverb or delay effects can take the basic texture of a simple vocal and stretch it into something epic and atmospheric. Here we’re using ValhallaDSP’s excellent free Supermassive delay. The Planetarium preset set 100% wet is great for turning a vocal one-shot into an epic atmosphere.

Granular effects can work brilliantly applied to vocals. These break the audio down into tiny elements and then rebuild them to create textures and synth tones, usually with modulation and randomisation applied. Tools like Arturia’s EFX Fragments, Output Portal or Ableton Granulator are perfect for this.

Basic vocal sample editing

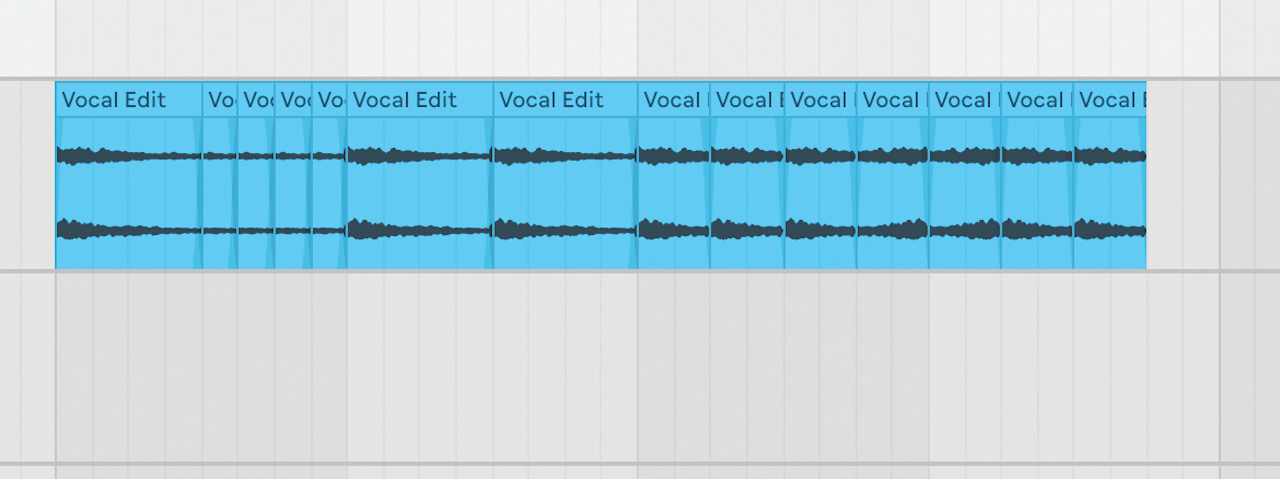

Wherever they’re sourced from, working with vocal samples is rarely as simple as dropping a loop into your track and being done with it. Let’s look at the basics of how we can adjust and edit sampled vocal phrases to create a fresh hook to work in a dance track. We’re working in Ableton Live as it makes it particularly easy to adjust timing of individual formants in a loop, but these techniques can be used in other DAWs and audio editors.

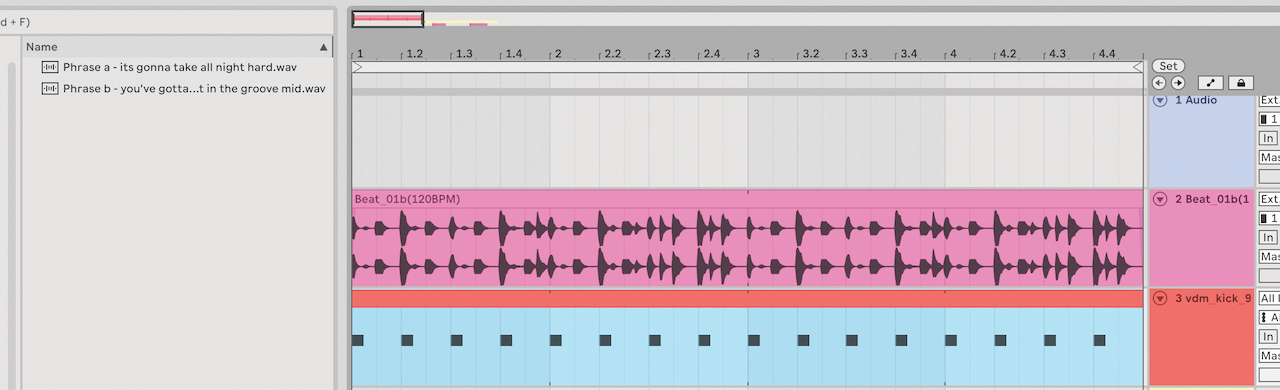

In this tutorial, we’ll take two short vocal phrases and turn them into a basic call and response hook for a dance track. We’re starting with a basic 4-bar drum loop that’s providing a rhythm for us to fit the samples around. Though our phrases are from the same vocalist, the timing, pitch and timbre doesn’t match, so some work is needed to make the fit.

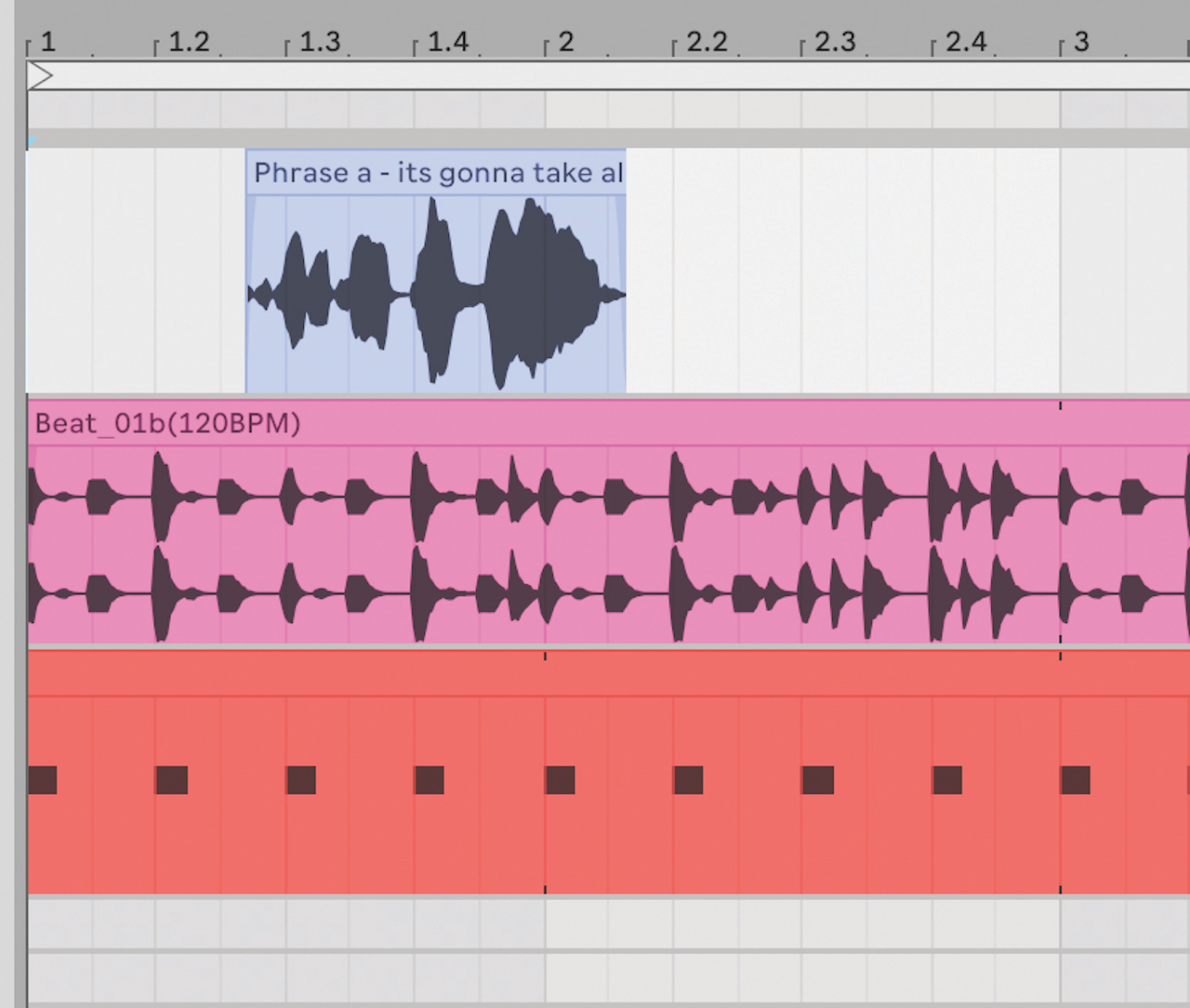

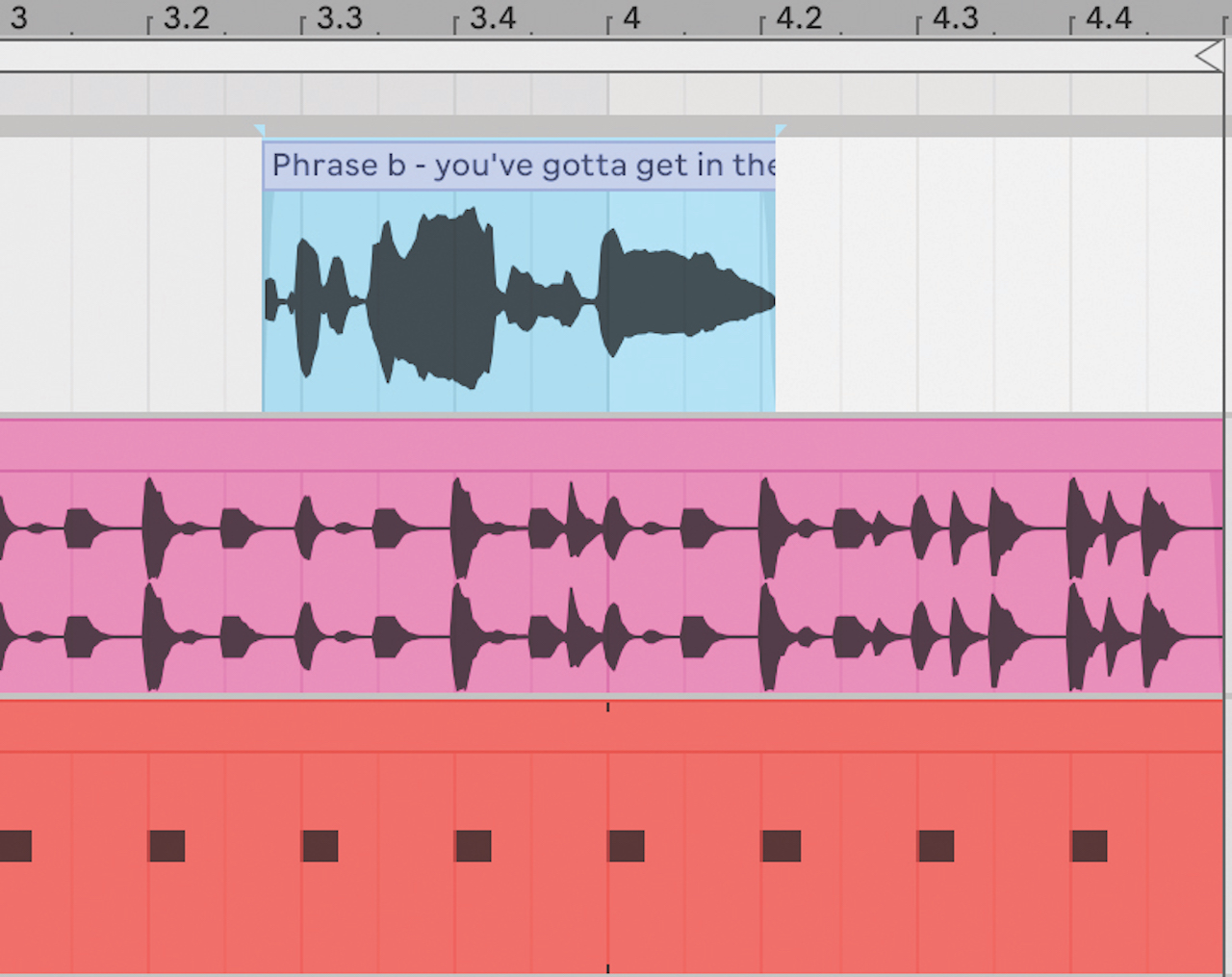

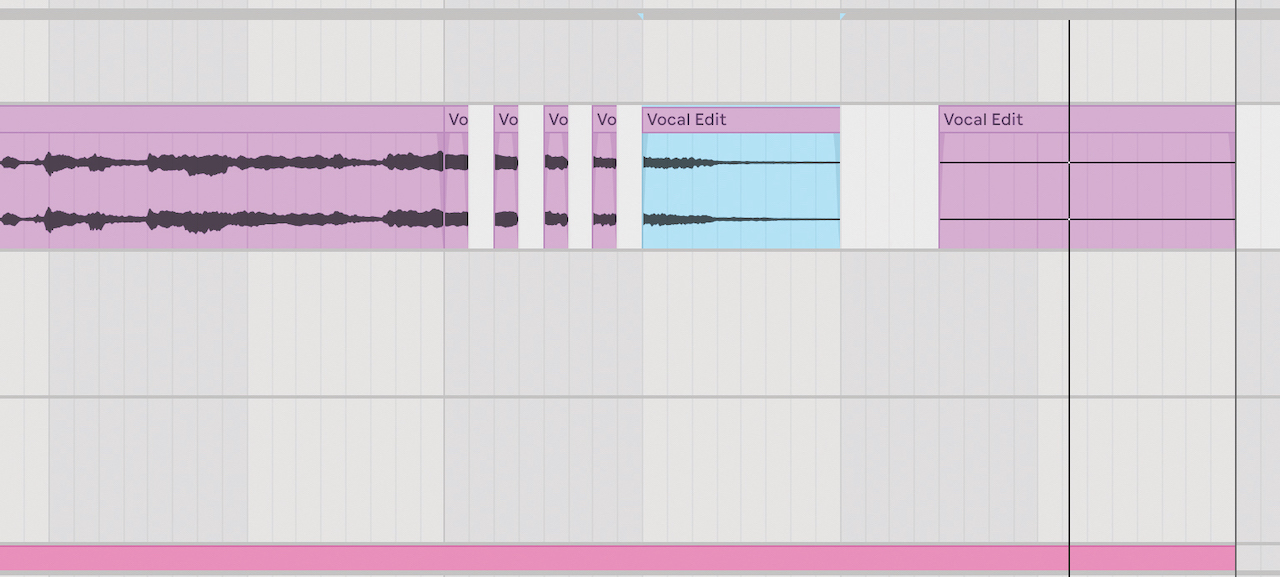

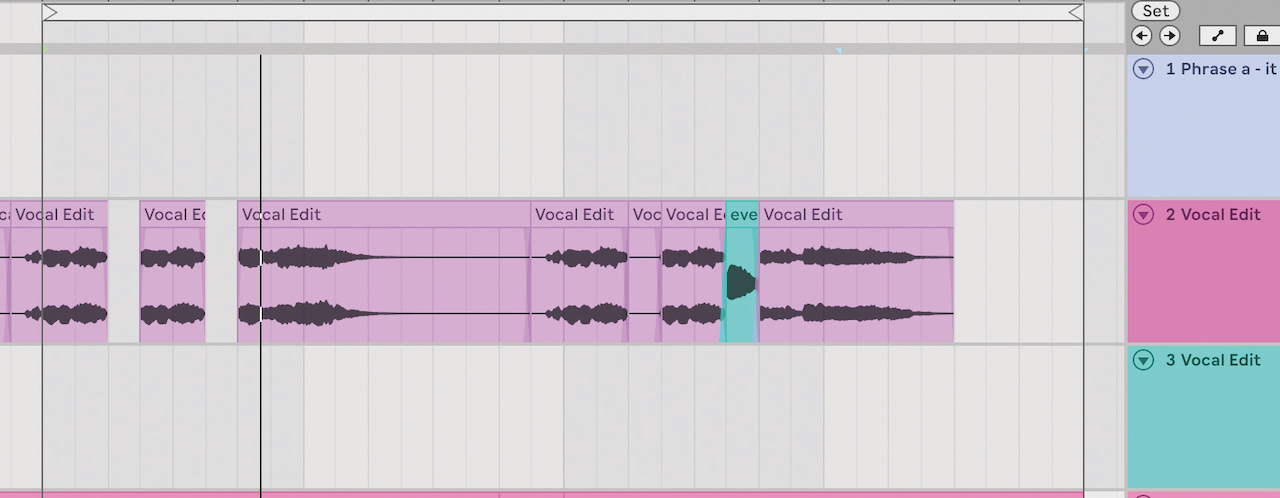

To start, we drag phrase A (“It’s gonna take all night”) onto an audio track. Initially we try placing the sample at the very start of the bar, but the timing sounds all wrong. Instead we move it to the midpoint of the first bar, beat 1.3. This is better, but it’s now obvious that the start of the word “gonna” should sit on the downbeat, so we shift the whole loop slightly forward.

Next we drag phrase B – “You’ve gotta get in the groove” – onto the third bar of the same audio track. Again, we find that the second word “gotta” makes sense on the downbeat, so we line that up with beat 3.3. The timing of the rest of the phrase still needs work though. For this, we turn to Live’s Clip View and warp the audio clip, using the Complex Pro algorithm for the best quality results.

Live’s warping tools let us place markers at the start of each syllable, making it easy to edit timing of the phrase. This requires experimentation: we want to create a rhythm that suits our drum loop without making it sound unnatural. We find something we like by shortening “get” and “groove” and loosely quantising key syllables to the beat grid.

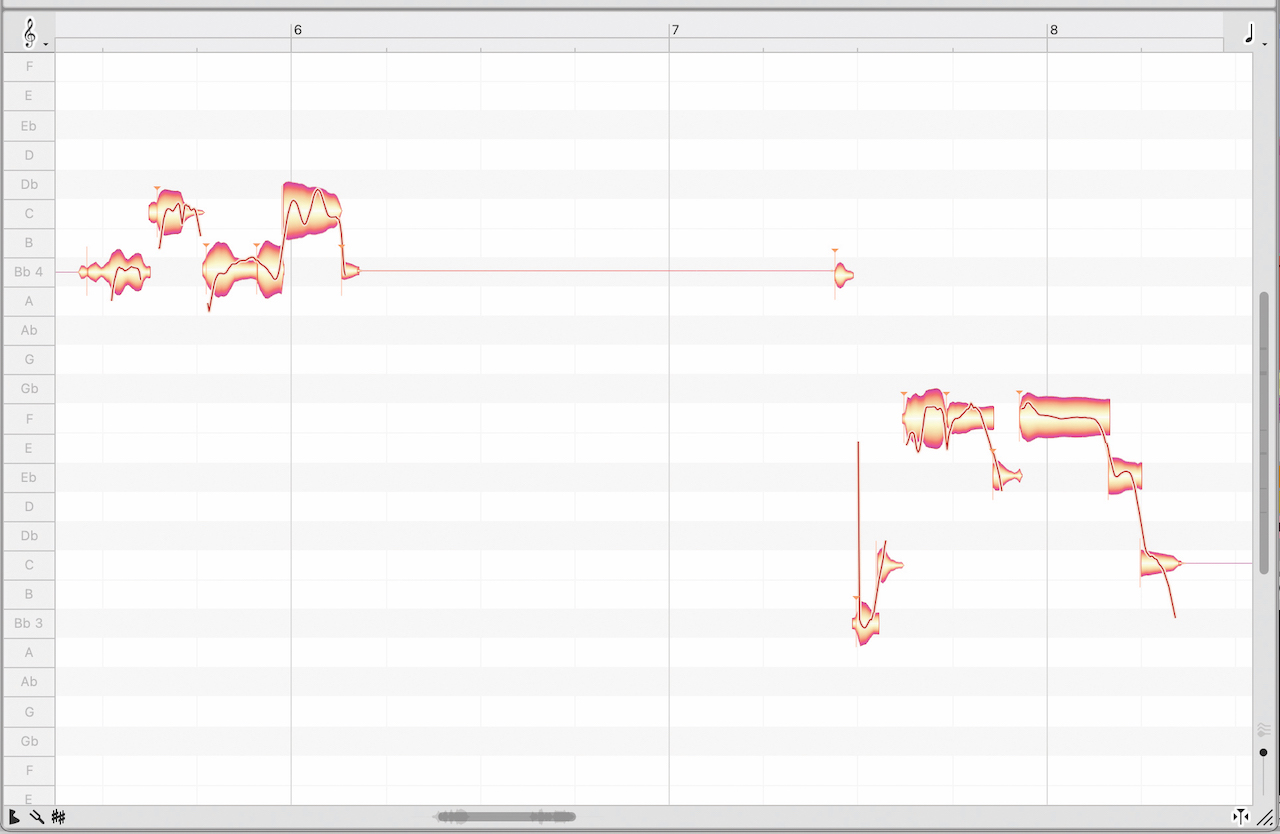

Next we look at the pitch of both phrases, using Celemony Melodyne. This analyses the pitch to let us see the precise tuning of our samples. Our closest key across the two phrases is Bb minor, but there are a few rough notes outside that scale in phrase B, which we alter with Melodyne. Phase A is a little sharp too, so we correct its tuning.

Finally, we tie the two phrases together with processing. First we use a preamp emulation to add analogue-style saturation. Next we use Ableton’s compressor to help add dynamic consistency. Reverb is great for placing disparate samples in a unifying ‘space’ too. An ’80s-style plate reverb treatment works great, with the dry/wet set around 15% so the effect is subtle rather than overbearing.

Working with one-shot vocals

The rise of the MPC in the late-’80s and ’90s created a new style of ‘finger drumming’ sample performance, where dexterous producers would slice sampled loops, assign individual elements to each pad and play new patterns in real time.

Although this was typically used for beats, the technique was also applied creatively to vocal sampling, resulting in the distinctive ‘vocal chops’ sound pioneered by producers like MK and Todd Edwards. The appeal of this style of vocal sampling, particularly for dance music, lies in the fact that it can treat vocal hooks, rhythmic and melodic elements alike.

Modern tech makes the technique easy to achieve. Most software samplers, and many hardware ones, allow the user to slice a loop into segments, either at the transients – usually the best approach to capture individual vocal syllables – or pre-defined intervals.

It can be beneficial to take a rough-and-ready approach to this form of sample slicing. Slice your loops, then connect an appropriate MIDI controller or sequencer and experiment with patterns till you find something inspiring. Don’t overdo quantisation. You can always return later and finesse loop points, tuning or timing.

Sequenced vocal effects

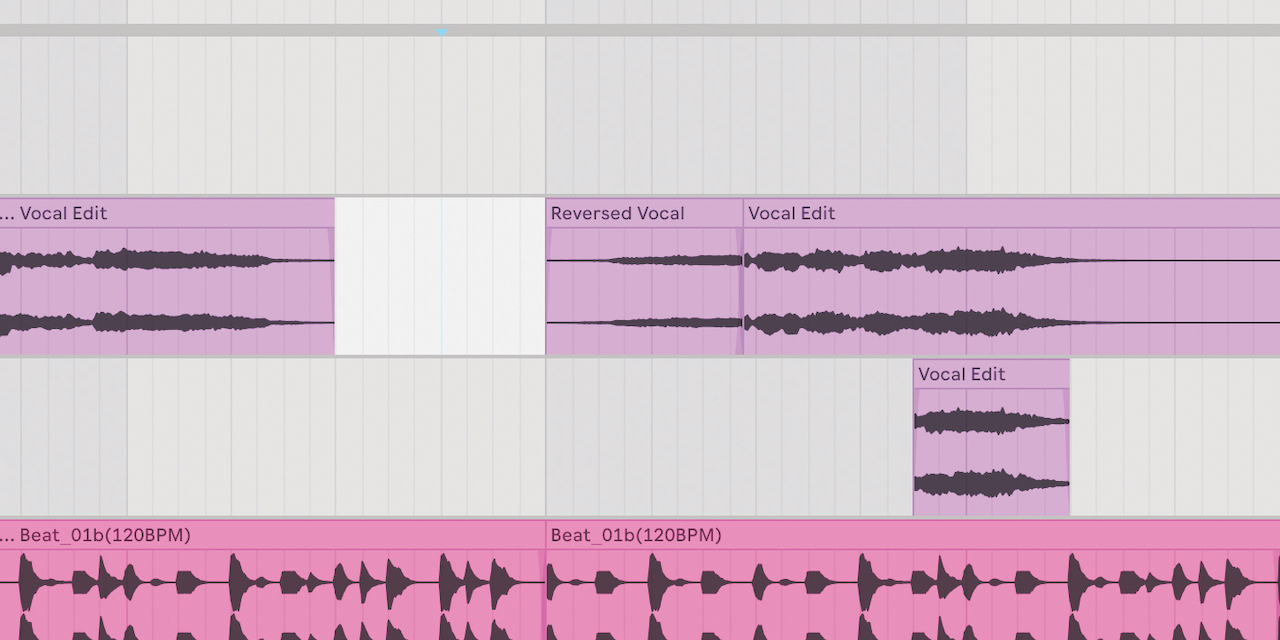

As we’ve explored elsewhere in this feature, it’s fairly common to apply effects such as pitch shifting, looping, reversing or time-stretching to vocal samples. This is often done at the ‘audio’ stage, using edits applied to clips on a DAW timeline, in an audio editor, or using the tools offered by a sampler.

Many similar approaches can also be applied via insert effects though. Sequencer or modulation-powered multi-effects are especially useful for this, as they allow the user to target effects to a specific section of a loop or phrase – for example, looping or reversing just the final beat in a bar. Many of these tools also let the user save and switch different treatments, meaning that they can be used to apply changing effects to a loop over time without the need to repeatedly edit audio. Here are three of the best sequencer-focused multi-effect tools...

1. Cableguys Shaperbox 3

ShaperBox is all about its custom LFOs, which allow the user to sequence or modulate all manner of effect parameters. Its TimeShaper plugin is especially good for ‘tape-stop’ and reverse effects.

2. Sugar Bytes Effectrix 2

This classic effect sequencer just got a major overhaul. For vocals, its dual looper modules are the highlight, but the vinyl style ‘scratch’ effect, granular and bitcrush effects can work wonders on vox too.

3. iZotope Stutter Edit 2

As its name suggests, iZotope’s effect sequencer is at its best when used for glitch-like stutters, which can work wonders on static vocal hooks. The added comb filter and reverb modes also sound great.

Enhancing a vocal loop with edits and one-shot FX

The beauty of working with sampled vocals is that you’re not beholden to preserving the performance, style or even meaning of your vocalist. Let’s take the basic two-line vocal hook we created earlier and add ear-catching creativity with a few simple edits.

We start by duplicating the word ‘night’ at the end of the first phrase and placing it on a new audio track below the main hook. We place a Roland Space Echo emulation on this new track and use a classic ping-pong delay preset set to 100%. We adjust the feedback so that the delayed vocal fills the gap between the first and second phrase.

Next, we duplicate the four-bar loop to make it eight bars long. Our vocal hook now repeats twice. To add some variation, we apply some quick rhythmic ‘chops’ to the final word, ‘groove’, on the second repeat. Applying tiny fade ins/outs of 2ms to each edit prevents any unwanted ‘pops’.

To create even more variation, we duplicate the word ‘groove’ from the end of the fourth bar and reverse it. We then move this and affix it to the beginning of the second loop (in the fifth bar). We lower the gain of this reversed section slightly, resulting in an effect that pulls us into the second loop of the vocal hook.

Our vocal hook is working well, but it’s not enough to sustain a full track. To get more out of it, we duplicate our loop again and re-edit it to create an alternate version, with the lyrics now saying “It’s gonna take, gonna take all night / It’s gonna take, gonna take you in the groove”. We’ve grabbed the word ‘you’ from another vocal loop to fill the gap.

Vocal sampling dos and dont's

DO: Try applying pitch and formant shifting to spoken word vocals as well as sung ones. Just because your source audio doesn’t have an obvious melody, doesn’t mean you can’t apply one with some careful editing.

DON’T: Get too hung up on creating vocal patterns that are comprehensible as real words. Pangaea’s recent club track Installation is a great example of a track that uses vocal syllables arranged in a manner to create an uncanny hook, recognisable as a human voice without actually forming proper language.

DO: Try performing your vocal edits ‘live’. That could be through the use of a MIDI pad controller to trigger single syllables, or else applying different glitchy effects using the MIDI triggering in the effect plugins listed above.