Brendan Cowell’s 2021 novel Plum has expertly wed two seemingly unnatural partners: rugby league and poetry. Cowell’s story is both an ode of love to rugby league, and a powerful exploration of the catastrophic effects of sport-induced brain injury.

This story has now been brought to life in an ABC drama of the same name. It brilliantly reflects the experience of many players who are left to suffer – often in silence – with the long-term costs of the game.

A theatre of damage revealed

Our introduction to the main character, Peter “The Plum” Lum (played by Cowell), is jarring. Plum’s body lies motionless in a darkened changing room, enveloped by the distant sounds of a roaring stadium full of fans, a sharp referee’s whistle and the commentator’s pitched voice: “this poor bloke, he has had his head absolutely battered”.

We watch the doctor’s light worryingly cast to and fro across Plum’s dazed gaze, while his heavily pregnant wife’s concerned face looms large. Much larger, however, is the coach’s demand: “get the salts doc” – and his insistence that “the only way he (Plum) isn’t going back out there (on the field) is if he is fucking dead”.

And so the act proceeds, with Plum, like many athletes before and after him, returning heroically to the field. Though his team is victorious – another trophy retained – we’re forced to consider the unspoken costs of his love for the game.

These costs are amplified once the adoration from Plum’s fans and teammates, and his mantle as Cronulla’s king, are no more. We come to know a shell of a man who is desperate to deny, despite the advice of his doctor, the cognitive and other effects of the “little jolts” and “hard head knocks” experienced throughout his career.

The intensity with which Plum keeps his health condition a secret, and the ongoing abuse he levels on his body, provide a window into the lived experiences of many rugby league players. While this game gives, it also takes more than its fair share.

Masculinity and collision sports

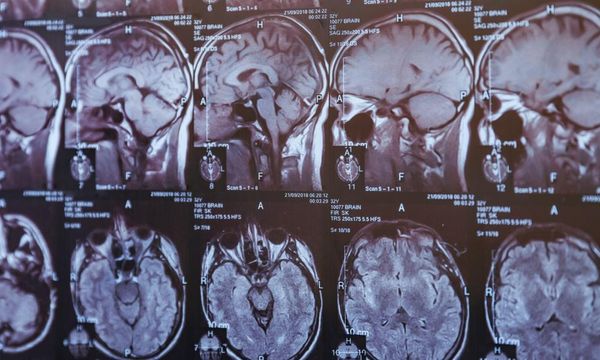

The series highlights the emerging scientific link between collision sports such as rugby league and degenerative brain conditions including CTE-induced dementia – as well as attempts to discredit this science and silence the voices of athletes and families seeking redress from league administrators.

Contact and collision sports have often required athletes to sacrifice their brains and bodies in the pursuit of glory and success.

While a diagnosis of the degenerative brain disease Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) can only be made posthumously, Plum displays many of the hallmark symptoms: impaired judgement, impulse control issues, aggression, depression and anxiety.

Viewers are taken into the deep fog of this existence. As a 1990s playmaker, Plum had fame but not fortune. Nearing 50, working at an airport, we see a traumatic near-miss as he experiences an epileptic seizure.

His forgetfulness leaves him unable to remember his favourite player’s name at a Cronulla Sharks corporate event. He suffers confusion and anxiety. Aggressive acts, including punching holes in bedroom walls, become his daily pain and shame.

Plum’s absent father’s advice to “never take a backwards step” also echoes throughout the series, reflecting the deeply embedded view of rugby league as a hard sport played by equally hard men.

This hard man veneer is grounded in stoicism – and for Plum and his former teammates, in unhealthy addictions to gambling, drugs and grog. Plum repels his family and friends, making his world intentionally small for fear he might forget something or someone. The series brings to the fore the raw and visceral effects of hypermasculinity and not speaking out.

Rugby league and poetry

The series also features poetry and the presence of past literary figures (conjured in Plum’s mind) such as Charles Bukowski and Sylvia Plath. As viewers, we see Plum’s internal dialogues with these apparitions, but his family and friends can’t.

Plum also joins a local poetry group, where his decaying brain finds purpose and connection. This unlikely outlet becomes his therapy. It comforts him and provides him a space to communicate his experiences with the outside world. Through his ode to rugby league, we witness him come closer to clarity.

Read more: Why a portrait of a former NRL great could spark greater concussion awareness in Australia

All the while, Plum’s son is a talented player on the verge of a professional rugby league contract. And although Plum doesn’t regret a minute of his playing career, his prognosis leaves him urging his son away from the sport’s theatre of damage. This is a decision echoed by many parents in real life.

The future of collision sports

Reflecting on the potential impact of his book and the ABC series, Cowell imagines a space where the competitive commercial rivalries between football codes such as AFL, rugby union and soccer are suspended.

Instead of competing for a greater share of the market via trivial one-upmanship, sport leagues could pool their resources to invest in science that helps us understand and prevent sport-induced brain trauma.

Considering how many rugby players conceal and/or fail to report concussive episodes, we’ll need a major cultural shakeup at all levels of the game – because a love for the game should never come at the expense of oneself.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.