This story contains details about sexual assault and suicide that some readers may find disturbing. If you or anyone you know is in need of support, you can contact the national Canadian suicide hotline at 1-833-456-4566.

“Britney Spears extends a honeyed thigh across the length of the sofa, keeping one foot on the floor as she does so. Her blond-streaked hair is piled high, exposing two little diamond earrings on each ear lobe; her face is fully made-up, down to carefully applied lip liner. The BABY PHAT logo of Spears’ pink T-shirt is distended by her ample chest, and her silky white shorts—with dark blue piping—cling snugly to her hips. She cocks her head and smiles receptively.”

So writes Steven Daly in his 1999 Rolling Stone profile of a seventeen-year-old Britney Spears. Lounging in a bra and polka-dot pajama briefs and clutching a Teletubby, Britney was the cover of the issue, the headline winking “Inside the Heart, Mind & Bedroom of a Teen Dream.” The cover renders the article too gross to read before one even arrives at the phrase “honeyed thigh,” but as one of the many horror shots from her adolescence, it’s an episode referenced only in passing in her long-awaited memoir, The Woman in Me, which was released on October 24.

An autobiography is an interesting project for someone like Britney, who has been written about in extensive, grotesque detail but who, for reasons both personal and legal, has remained relatively silent for much of her career. With the help of ghostwriter Sam Lansky, The Woman in Me recounts Britney’s humble Louisiana upbringing before her meteoric rise to teen stardom. While the memoir divulges her early-aughts relationship with Justin Timberlake—leaked details of his philandering and attempts to imitate Black culture kept Page Six afloat in the weeks surrounding the launch—the bulk of the book maligns a villain far more pernicious than Timberlake and his ill-fated blaccent: Britney’s father and conservator, Jamie Spears. For thirteen years, Britney was deemed mentally unfit and held in a conservatorship against her will by her alcoholic and abusive father. “I try not to think too much about my family these days,” she writes. “But I do wonder what they will think of this book.”

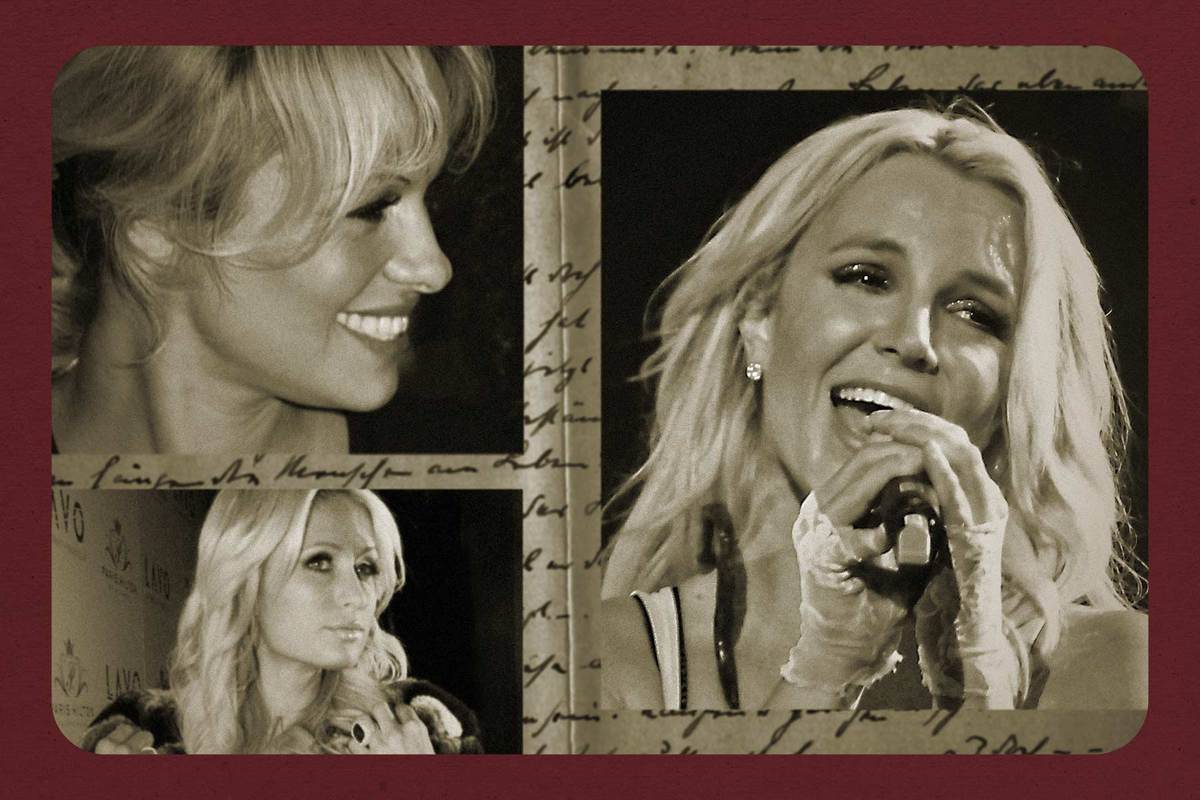

Jamie is but one of many who wanted a piece of Britney. In the 2000s, bloggers like Perez Hilton and an oppressive tabloid culture hounded starlets around the clock. But we’ve started to apologize to the famous women we once sought to destroy. The spirit of the moment is cultural atonement and ethical consumption—and the bombshell is having a reckoning. Fans rallied around a #FreeBritney movement to save the pop star from her conservatorship; the documentary Pamela: A Love Story (2023) sought to rectify the abuse once heaped upon Playboy centrefold Pamela Anderson; comedians like Sarah Silverman have apologized to Paris Hilton for picking on the socialite. That each of these women has now penned a memoir (Anderson’s Love, Pamela published in January, and Hilton’s Paris Hilton: The Memoir came out in March) demonstrates a desire to seize ownership of a narrative that has been far beyond their control.

Celebrity memoirs have long been financial boons for the publishing industry and celebrities alike. They gained prominence with eighteenth-century French courtesans who chronicled their escapades in order to recoup legal fees, Hannah Yelin notes in her book Celebrity Memoir. Pamela Anderson’s and Paris Hilton’s books were both New York Times bestsellers, and Britney Spears made a reported $15 million (US) from her memoir, which was a bestseller on Amazon three months before it was even released. Big-name memoirs are the backbone of a book industry in rapid decline. But whereas they may have once been thought of as cash cows that sell out only to line the shelves of Salvation Army thrift stores, increasingly, celebrity memoirs have cultural cachet. Child star Jennette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died (2022), with its recounting of her troubled childhood, was a darling among critics. The New Yorker staff writer Rachel Syme constructed a thirteen-part series, dedicated to her appreciation of the art form, on the magazine’s website. “These books reveal as much as they hide,” Syme writes. “For women and minority stars, especially, a memoir could help bridge the gap between what was experienced and what could be said.” The memoir offers more than salacious gossip and a jumpstart to waning careers: an opportunity for women defined by their images to finally speak.

The Woman in Me begins with Britney’s childhood in Kentwood, Louisiana, a town built around a Confederate training base. Britney describes Kentwood as the kind of place where “doors were left unlocked” and “social lives revolved around Church and backyard parties,” but there was a prevailing darkness in her home life. “Tragedy runs in my family,” she writes. Her paternal grandfather abused her grandmother, Jean, and when one of their children died at three days old, he had Jean institutionalized in an asylum and put on lithium. “In 1966, when she was thirty one, my grandmother Jean shot herself with a shotgun on her infant son’s grave,” Britney writes. The spectre of Jean’s confinement looms over Britney, as does a cycle of abuse. Jamie’s financial situation yoyos throughout Britney’s childhood, with his alcoholism always tethering the family to poverty. Fortunately, Britney is a natural performer, and “before too long, my parents set their sights on bigger opportunities than what we could accomplish picking up prizes in school gymnasiums,” she writes. After a stint with Natalie Portman as an off-Broadway understudy, she finally lands a gig as a mouseketeer on The Mickey Mouse Club alongside nascent talents like Christina Aguilera, Ryan Gosling, and her eventual boyfriend Justin Timberlake.

By seventeen, Britney has a record deal, a number one album on the Billboard 200, and a high-profile relationship. Her accomplishments mount quickly, but it’s hard to get excited about her surging career—we know how this story goes; Britney is haunted by more ghosts than just her grandmother’s. We’ve followed not just Britney’s life in tabloids but the travails of starlets like Lindsay Lohan and Mischa Barton and, before them, sex symbols Tara Reid and Pamela Anderson and, before them, studio stars Marilyn Monroe and Veronica Lake and Jean Harlow. The beats of the bombshell’s memoir, and the bombshell’s life, take on a devastating familiarity. Britney’s memoir adheres to genre: there’s a troubled childhood, one in which the memoirist is something of a meal ticket.

A threat of sexual violence also permeates the genre: Britney’s precocity is weaponized against her—by reporters inquiring into the status of her virginity, by old men in the audience she describes as “leering at me like I was some kind of Lolita.” Other memoirists recount having been abused as children: Anderson writes that she was six years old when she was molested by a babysitter; she was raped at twelve or thirteen and never spoke of it and was gang-raped in high school. She writes that she was relieved not to have to worry about being pregnant because she did not yet have her period. Paris Hilton recounts being raped at the mall by an older man when she was a high school student and the sexual assault she endured at a boarding school for troubled teens. In many a bombshell’s career, sex is for the public’s taking: Anderson’s sex tape is stolen from a safe within her own home, and a nineteen-year-old Hilton’s tape with her thirty-one-year-old boyfriend leaks to the internet.

Still, the moments when money and fame finally do come calling are dazzling—like in Love, Pamela, when famed producer Jon Peters sets Anderson up in his Bel Air mansion with a Mercedes 420 SL, or when Britney gets the call that she’s the first woman to debut with both a number one album and song and she no longer has to subject herself to mall tours. These victories are so enamouring that they temporarily render past indignities worth it. But they also make a fall from grace that much more painful. Anyone studied in the celebrity memoir knows the fall is almost inevitable; the half-life of a bombshell is so fleeting, a woman can’t really last in the public eye for more than a few years before her admirers turn cannibalistic and appetites for access can no longer be sated.

“Don’t let them do to you what they did to me,” Pamela Anderson recalls Jane Fonda warning her in Love, Pamela. Don’t let them do to you what they did to me would be an apt title for this genre. They do, of course, do to Anderson what they did to Fonda, another pin-up girl vilified by the press. They steal Anderson and Tommy Lee’s sex tape after burglarizing her Malibu home, they extort her for rights, they publish the video when she and Lee tell the Penthouse publisher to “go fuck himself.” What they do is an amalgam of ways in which we strip these women of agency and privacy and punish them for ever having had the audacity to be young and beautiful or, even worse, to grow old.

Britney is not allowed to grow old and is placed under legal confinement that renders her perennially infantile. In 2007, in the midst of a vicious divorce and custody battle and rumours of drug abuse, she is photographed with a shaved head, brandishing an umbrella at a paparazzo who heckled her about not being allowed to see her two young sons. “Nobody seemed to understand that I was simply out of my mind with grief,” she writes. In 2008, Britney’s confinement is made legal; a SWAT team is called to her parents’ home and Jamie Spears is named the conservator of his daughter’s estate and person. “I’m Britney Spears now!” she recalls him yelling.

The details of Britney’s conservatorship have been thoroughly reported, but they’re especially devastating in her own telling: her father controls what she eats, who she dates (prospects, in turn, were notified of her complete medical and romantic history ahead of a first date), and when she can see her children, and he also installs parental controls on her iPhones. She’s forcibly medicated—“It wasn’t lost on me that lithium was the drug my grandmother Jean, who later committed suicide, had been put on,” she writes. Britney has less freedom than when she was in grade eight drinking cocktails nicknamed “toddies” with her mother. She’s suspended in adolescence. Her tours gross hundreds of millions of dollars and she books a lucrative Las Vegas residency, but she claims she has limited access to her earnings, which disproportionately fund her father and his lawyers. Britney describes herself in these years as something of a “child-robot.” “I became more of an entity than a person onstage,” she writes.

The child-robot is an enduring trope across celebrity memoirs—“As a teenager, I created her,” Hilton writes in her book. “The dumb blonde with a sweet but sassy edge. People loved her. Or they loved to hate her, which was just as marketable.” Fame is often presented as empowering, a woman’s sexuality is empowering, but frequently, these women come up against the limits of an image they don’t totally own. Anderson recalls when her Baywatch character, CJ, got her own Barbie. The CJ Barbie was a bestseller; Anderson says she did not receive a dime from it. Girls across America played with mini CJs, millions of users logged online to peep on a moment of intimacy between Anderson and her husband, a woman was so compelled by Baywatch that she broke into Anderson’s home and tried on the infamous red one-piece before sneaking under Anderson’s covers. “No matter how I tried, the image was bigger than me and always won,” she writes. “My life took off without me.” Love, Pamela is a sort of diary, a reminder to Pamela Anderson who Pamela Anderson really is.

Britney’s been written about, not just by leering journalists but by her mother, who penned her own memoir in the mid-aughts when Britney’s breakdown was most public, and by her teen-star sister Jaime-Lynn, who wrote Things I Should Have Said when #FreeBritney started picking up traction. There’s also been a slew of documentaries maligning her conservatorship, none of which Britney herself consented to. Anderson was similarly outspoken that she wanted no involvement with the Hulu biopic Pam & Tommy, which dramatized the couple’s infamous sex tape and its theft.

In 2021, Britney finally speaks for herself, in front of a Los Angeles probate court, to contest her conservatorship. “My voice has been used for me, and against me so many times that I was afraid nobody would recognize it if I spoke freely,” she writes about her fears of testifying. “What if they called me crazy?” The courts rule in her favour. She’s free, her father no longer controls her estate and person, she can marry her boyfriend, and she can remove her IUD and get pregnant like she’s dreamed of doing for years.

But it doesn’t take long for public opinion to shift—they do, of course, call her crazy. After a series of erratic Instagram posts, including one video of Britney wielding fake knives like maracas in an eerily choreographed dance, whispers that the conservatorship wasn’t so bad after all begin to swarm online. An #UnfreeBritney hashtag picks up traction. None of our neon signs or soul searching about how we mistreated famous women mean anything. Jamie Spears is not some abstract antagonist but a mirror image of our own ugliest impulses: to see this woman punished for partying too hard and showing too much skin, for pretending to be a virgin and then breaking her word, for promising to let us inside her teen bedroom and never following through, for getting money, fame, a hot boy-band boyfriend, and everything else we wanted and still having the nerve to act out. Maybe Britney is crazy; who wouldn’t be?

When you give part of your paycheque to an artist, when you play with a C.J. Parker Barbie in your living room, there’s a level of access you can naturally come to expect. And while a tell-all promises to do just that, transcribing one’s own life is also a project of omission. The Woman in Me is evasive. It’s not Britney who recorded her audiobook, it’s Oscar-nominated actress Michelle Williams. Britney refers to her ex-husband Sam Asghari as a “gift from God” but makes no mention of their divorce in August. And the cover shows a twenty-year-old Britney, the forty-two-year-old woman somewhat obfuscated by partially ghostwritten prose. Despite all I had read about Britney’s mistreatment, it annoyed me, really: the hardcover costs $39.99, not to mention that Britney’s pop princessdom is contingent upon similarly paying fans. Didn’t we make her famous to begin with, after all? Wasn’t it eagle-eyed social media users who hunted out clues about her well-being to ignite the movement that would #FreeBritney?

There’s no end to what we want from these women: not just Britney, Pamela, and Paris but also Jessica Simpson, Sondra Locke, Cybill Shepherd, Frances Farmer, and Lauren Bacall, all of whom penned memoirs. Our appetites are insatiable—we want access to their sex tapes and rights to the biopics that apologize for us accessing their sex tapes. I’m still rapturously curious about how and why these editorial decisions in The Woman in Me were made, but there are some elements of Britney’s life that I don’t deserve to know.

Correction, November 27, 2023: An earlier version of this article stated that Britney Spears had a number one song on the Billboard 200 by the time she was seventeen. In fact, it was a number one album; she had a number one song on the Billboard Hot 100. The Walrus regrets the error.