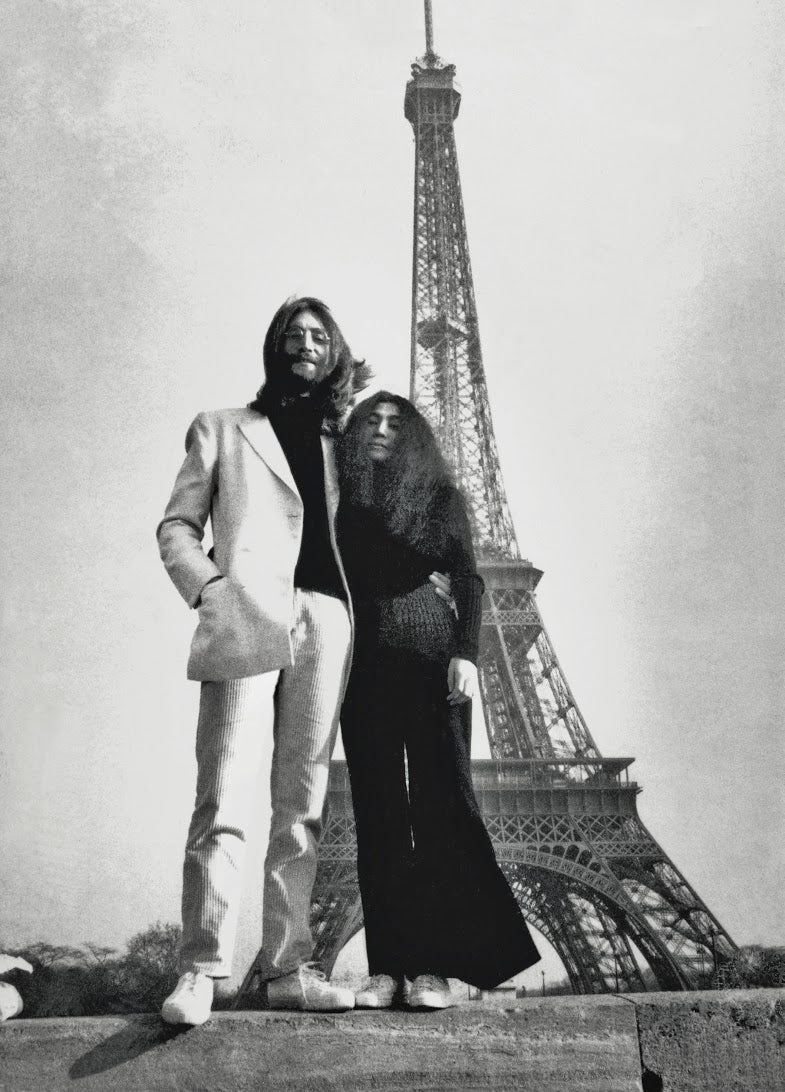

On 13 September 1969, John Lennon – the Beatle most quickly heading for the exit door – played the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival festival under the name Plastic Ono Band. For the first time he appeared on stage with his wife of six months, Yoko Ono. She and Lennon had been together since 1967, but within and without the Beatles’ industrial-cultural complex the Japanese artist remained, as dutifully inscribed rock lore has it, a divisive figure.

Yet performing that night in Canada, as she took her place alongside her husband, Ono was united as an artist with perhaps the greatest songwriter in the world. Was there, finally, a feeling of acceptance from Lennon’s fans?

“I don’t know about that. I still don’t feel that John’s fans are accepting me,” Ono, who is now 88, replied when I asked her that question 11 years ago. “I don’t know who’s really John’s fans, and who’s really John and Yoko fans. The Beatles fans, some of them really denounced John in a way. So I don’t know who’s who. So whenever I create something – make an album or something – I never think about who’s gonna listen to it. It’s a waste of time. You would never know.”

Ono and I were talking in Reykjavik on 9 October 2009, on what would have been her late husband’s 69th birthday, and which was also the 34th birthday of their son Sean. We were in Iceland because, in her role as the keeper of Lennon’s flame, she was also the keeper of his light. Ono was unveiling the Imagine Peace Tower, a column of light shooting into the sky that she’d first conceptualised as an artwork in 1967. It would stay lit for two months, until 8 December, the anniversary of the day on which Lennon was murdered in New York in 1980.

That autumn, Ono had also just released a new album, Between My Head and the Sky, produced by Sean and credited to Plastic Ono Band. The name had lain dormant since she and Lennon used it for 1975’s Shaved Fish compilation. She explained to me how the Plastic Ono Band concept predated her meeting her future husband. Invited to perform a concert of some sort in Berlin, the avant garde artist decided she would “simulate the popular band thing – we’ll have four plastic artwork stands, and each stand would have a tape recorder inside. And that was my band.

“Then when we got together I said: ‘Oh John, I had this invitation to Berlin,’” she continued, recalling how she told the Beatle that her satirical take on a fab four-piece would also be holding plastic toothbrush-holders and plastic pillboxes. “And he said: ‘You should call it Plastic Ono Band.’ Just like that! He is so quick!” marvelled Ono, still referring in the present tense, as she often did, to a man then dead for 29 years.

This month, Plastic Ono Band lives once again, in a blockbuster release of the 1970 John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album. The Ultimate Collection is a 50th anniversary “super deluxe” box set that promises the “ultimate deep listening experience” of Lennon’s first solo album after the end of The Beatles in April that year.

Over 11 hours and eight exhaustive discs (comprising demos, raw studio mixes, out-takes and so on), here is the primal howl of album opener “Mother”, sounding more traumatised still, and never more starkly than on the vocals-only “Elements” mix, which foregrounds the anguish of a child abandoned by both parents: “Mother, you had me but I never had you… Father, you left me but I never left you”. Here, too, are the original 51 breath-stealing seconds of the climactic “My Mummy’s Dead” stretched to 75 seconds: a nursery-rhyme lament in which raw loss echoes, and echoes, down the decades – as does Lennon’s strength in weakness.

“If you think about it, how many other alpha-male rock’n’rollers would write a song called ‘My Mummy’s Dead’?” wonders Richard DiLello, The Beatles’ press assistant at their company Apple Corps who, during that pivotal year of 1970, photographed Lennon and Ono on several occasions. “And the choice of words is interesting. It’s not the formal ‘mother’. It’s ‘mummy’, the most intimate term you can use you with your mother.”

This, though, was where Lennon’s head was at in the months following the end of The Beatles: searingly honest, self-lacerating, self-fulfilling.

On the one hand, says DiLello – author of the brilliant Apple insider’s account The Longest Cocktail Party (1972) and now, aged 75, living in Ohio – “John was in a very good place.

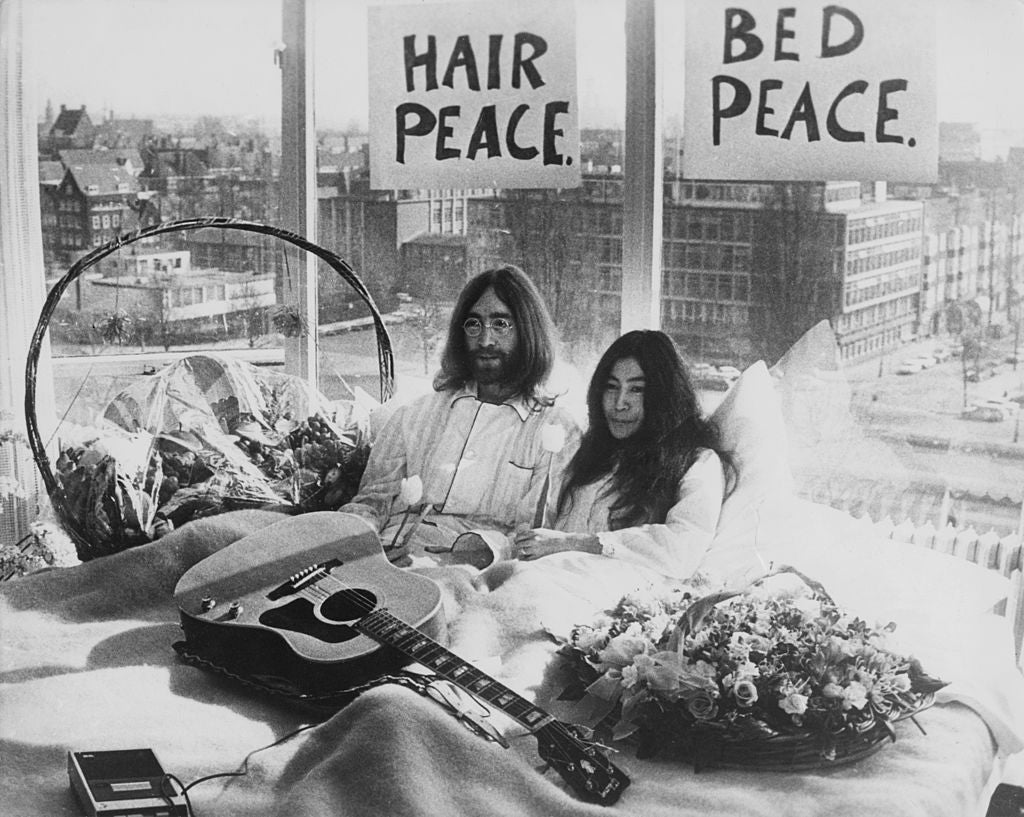

“He was very happy with Yoko, and prior to this they were working non-stop on their peace campaign, starting with the Amsterdam ‘bed-in’ in 1969, then getting married and going on their honeymoon. He was very productive; he never stopped doing stuff. I mean, all of the Beatles had enormous reserves of energy.”

For Lennon, that found form in three solo singles, “Give Peace a Chance”, “Cold Turkey” and “Instant Karma!”, none of which would appear on Plastic Ono Band. DiLello recalls accompanying Lennon and Ono to Top of the Pops, where they recorded a performance of “Instant Karma!” on 11 February 1970.

“It was a powerful statement like you’d expect from John Lennon. And it was so different – coming after ‘Give Peace a Chance’, [this was] a hard-hitting statement, and the sonic landscape of that song was very different. It was very hard-edged. There was a buzzsaw, punk sound almost to it.”

On the other hand, Lennon wanted toboldly explore new places. That almost-punk sound, notes the American, was emblematic of Lennon’s desire to plant a flag in a fresh musical direction, “especially in the wake of their sessions with Arthur Janov and primal scream therapy. That opened up the door for a completely different period in his life, letting out all the demons.”

The Californian psychotherapist treated Lennon and Yoko in London that spring, and then, over four months, in Bel Air in Los Angeles. Lennon was curious about a treatment where, as he put it, patients “get to do this thing and then they scream and feel better… OK, it’s something other than taking a tab of acid and feeling better. So I thought, ‘let’s try it’… In the therapy you really feel every painful moment of your life. It’s excruciating. You are forced to realise that your pain, the kind that makes you wake up afraid with your heart pounding, is really yours and not the result of somebody up in the sky. It’s the result of your parents and your environment.”

“That therapy gave John permission to talk about things that were important to him that he never was able to put into songs before,” says DiLello, “that didn’t fit into the format of the band. This was all very personal stuff. He had a lot of demons that he had to address from this whole period of his life when he’d been abandoned as a kid by his mother and father. Then he went from being a kid to being the most famous guy in the world. He had a lot to deal with in a very short period of time.”

Musician and illustrator Klaus Voormann, a member of The Beatles’ inner-circle who performed in Toronto and played bass on Plastic Ono Band, had by then known Lennon for the best part of a decade, since the band’s Hamburg days. He was aware from early on in their friendship how troubled Lennon was by first the absence, and then the death, when he was 17, of his mother Julia.

“In the very beginning he wasn’t really talking much about it,” he says, “then he started talking about it. But I tell you this, it’s really true: until Yoko came on the picture, he was an unhappy person. Even having so much money and success, John was not happy.”

The German remembers how, after the sessions with Janov, “John and Yoko were both like little kids – they were crying, then they were laughing, very open. They were like an open wound,” he tells me over the phone from Bavaria. “And John wanted to get rid of this feeling by writing those songs. That’s why, to me, this is such a strong record – apart from the fact that I’m playing on it!” the 82-year-old laughs.

For Ono, this was part of a creative process that began as soon as she and Lennon met. Lennon recognised that a fellow artist, albeit one from a wildly different tradition and discipline, would revive and increase his musical potency.

“Something was kicking in,” Ono told me in December 2009. Two months after meeting in Iceland, we were in Tokyo for the annual Dream Power charity concert she hosted at the 12,000-capacity Budokan arena, location of The Beatles’ summer 1966 shows in the Japanese capital. “But I didn’t know anything about that really. It just felt that he was… Well, you can say that I thought that he was curious about me.” Lennon didn’t need her to “liberate” himself, Ono insists; he was capable of that on his own. “It’s just that he needed somebody to lean on.”

I asked how she responded to Lennon’s announcement to Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr on 20 September 1969, one week after the Plastic Ono Band Toronto show, that he was leaving The Beatles.

“I said, ‘Oh Jesus.’ Because I wanted some space for my own work.”

So she didn’t want him to end The Beatles?

“No! What is he thinking? But he was kind of like threatening me: ‘Now it’s you and me, OK?’ I think he sussed that maybe I might leave or something… But I think he felt that what I was doing was more exciting. Only because they were doing it for how many years together.”

When I suggested to her that, after The Beatles broke up, she might have thought, “Great, a whole new adventure for John and me as artists,” she shook her head and said firmly: “No, I didn’t.

“It was very difficult for me because – and I said this to John and he was very upset – I was always a lone wolf. I did my things by myself. I had assistants, like my [former] husband [Tony Cox, whom she married in 1962 and divorced in 1969],” she said with a smile. “But I never had a situation where I had to do things with another person. And John was so used to it. John had a partnership with three people, and especially with Paul. So I was feeling not particularly excited about that. I felt like my power was halved.”

And Lennon felt his power was doubled?

“Yeah, yeah, yeah. Exactly!” Ono beamed. “Isn’t that amazing?”

Free of The Beatles, Lennon leaned on his new wife intensely – and protected her. In the summer of 1970 she suffered a second miscarriage, having already endured one in November 1968.

“That was a big deal,” says DiLello. “They wanted to start a family and everything was working against them. They were still recovering from the police hounding them and busting them previously [on drugs charges in October 1968]. And also, Yoko was under this great blanket, this great blizzard of racism from the tabloid press. There was this free-floating feeling that she was an undesirable, and the public didn’t approve of Yoko.”

That fed into the album’s second song, “Hold On”, a mantra of encouragement and reassurance to Lennon’s partner and their partnership.

“They had to be strong as a couple,” says DiLello, “they couldn’t get derailed by all this negativity, which was coming at them left, right and centre.”

Or, as Lennon put it, describing the song’s message: “It’s now, this moment. That’s all right, this moment, and hold on, now. We might have a cup of tea or we might get a moment’s happiness any minute now. So that’s what it’s all about, just moment by moment. That’s how we’re living – cherishing each day and dreading it, too. It might be your last day – you might get run over by a car,” he added, a pointed reference to the manner of his mother’s death.

Equally, this new freedom found form in the couple’s political activities, from the bed-ins to their support for the Black Power movement. In 1970 DiLello also photographed the couple alongside activist Michael X at a fundraising event in London at which they auctioned off their newly shorn hair and “a pair of Muhammad Ali’s boxing shorts, covered in blood. That’s a perfect media event, the meeting of these two disparate worlds, bohemian artists and a very aggressive political figure in London at the time – who was eventually hanged in Trinidadfor being involved in a murder [as part of] internecine warfare in the Black Power movement.”

On Plastic Ono Band, that personal-is-political bite manifested in “Working Class Hero”, although in a manner more nuanced, Lennon griped, than audiences often realised.

“I was thinking about all the pain and torture that you go through on stage to get love from the audience who really despise you... in a subtle way. They demand something from you… The thing about the song that nobody ever got right was that it was supposed to be sardonic. It had nothing to do with socialism, it had to do with: if you want to go through that trip, you’ll get up to where I am, and this is what you’ll be – some guy whining on a record, alright?”

Still, Voormann remembers well how fired up his friend was by the sociopolitical struggles that characterised the end of the Sixties, figuratively and literally.

“To me it was surprising that he was getting so much into this. I witnessed calls when we were in the studio doing the Imagine LP [in 1971] and suddenly in the middle of a take, more or less, Yoko comes in: ‘I just talked to Michael X, you have to call him back!’ That was a little disturbing, and was not really helpful for the session. And did not help us at all!”

There’s another bold lyrical statement in “God”, the last full song before the short coda of “My Mummy’s Dead”. To a roll-call of deities, figureheads and concepts in which he has no faith, Lennon adds: “I don’t believe in Beatles”. What do the men who were there around the recording of the album between late September and late October 1970 make of that totemic line?

“Again, that’s confessional,” replies Richard DiLello. “He’s saying: even though this was the most important part of my life at one time, it no longer is – but you can’t walk away from a legacy just like that. [He knows] that’s with you forever. Maybe he didn’t want it to be, but that was a fact of life.”

“He meant [he didn’t believe in] everything, not just Beatles,” offers Voormann. “He just wanted to make sure everyone understood that: ‘All I believe in is myself, and Yoko.’ Just those two. It was incredible. It’s a good statement. He didn’t want to believe in Jesus or nothing like that. He just wanted to believe in himself. And that made him strong.”

Released on 11 December 1970, Plastic Ono Band was a hit, but a modest one compared to the Beatles’ albums, and even compared to George Harrison’s solo debut, the triple-album All Things Must Pass, released the previous month. No matter: now it’s regarded as one of rock’s all-time great albums. And, of paramount importance to John Lennon at the time, he had made the album he wanted – needed – to make. As best he could, the musician had taken a wrecking ball to the edifice of Beatlemania, to reveal the man, the orphaned boy, behind.

“It was necessary for him to say: ‘OK, this is the way it was in the past, and I’m tired of being angry,’” thinks DeLillo. “It was cathartic for him. None of us want to carry around a ball and chain from womb to tomb. He wanted to have a mentally healthier life, which he did achieve once he got to New York.”

But before he and Yoko Ono could begin that life in New York, they had another trip to undertake. In Tokyo in January 1971, John Lennon met his new in-laws for the first time. When Ono and I were there 11 years ago, I asked whether he had made an effort for afternoon tea with her well-to-do family.

“No, he didn’t in the beginning. He just went to my parents’ place unshaven, and wearing an army surplus coat. Just the most hip outfit, very rock’n’roll! I mean, rock’n’roll can be a performance in a theatre, a beautiful, gorgeous thing. But he was just looking like a bum. This kind of ‘here I am’ attitude.”

Ono, though, wasn’t embarrassed or disappointed. “I thought it was a riot,” she said with a smile.

John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band – The Ultimate Collection is released on Capitol/UMC on 23 April