As an appeal to middle Australia, to the voters politicians routinely describe as working families or battlers, the Morrison government’s centrepiece budget move to halve the fuel excise for six months has obvious attractions.

“A family with two cars who fill up once a week could save around $30 a week or around $700 over the next six months,” declared Treasurer Josh Frydenberg on budget night, a point he’s repeated many times since.

But our calculations show most households, particularly those on lower incomes, won’t gain anything near the amount touted by Frydenberg.

At a cost of about $3 billion, cutting 22 cents in tax from every litre of petrol for six months will disproportionately help wealthy households. The economic gain is doubtful. Depending on what happens with the global oil prices, it may even contribute to inflationary pressures.

Who benefits most?

We’ve calculated the effects of the fuel excise cut on household budgets using a computer model developed by the National Centre For Social And Economic Modelling.

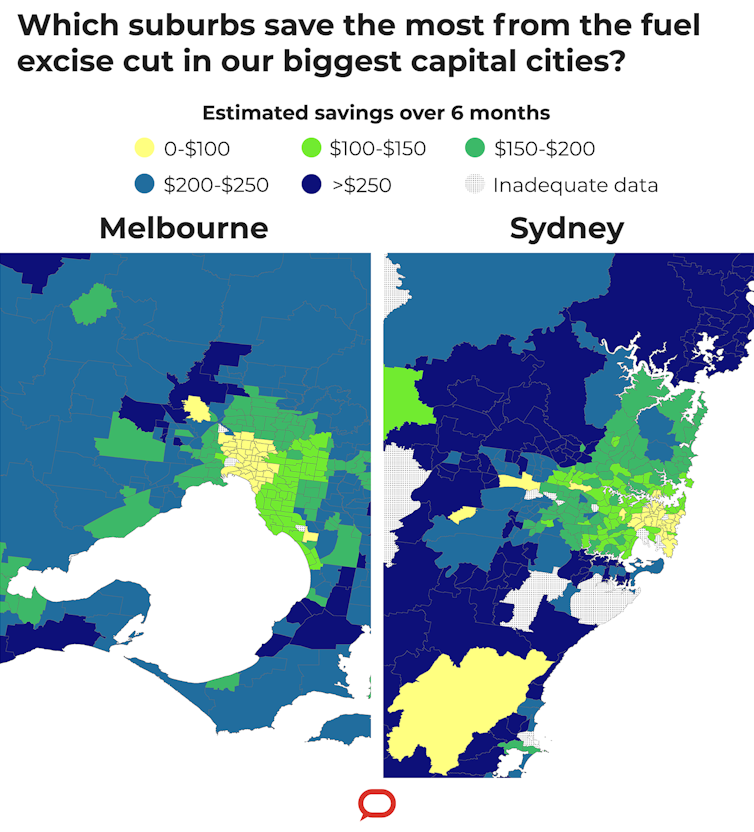

Our results show the six-month cut to the fuel excise will save the average household in inner-urban areas of Sydney and Melbourne about $132. The average households in outer suburbs will save about $242. Those in the outer suburbs of smaller cities will save less as they need to drive shorter distances. The average household in rural and remote areas will save $194.

These amounts reflect average outcomes across all households, including those with just one vehicle, or no vehicle.

It’s possible some two-car households will save the $700 cited by Frydenberg, but not many. That would require a household spending well over $10,000 a year on petrol, buying about 150 litres a week.

The budget papers themselves say the cut will “deliver an average benefit of around $300 to households with at least one vehicle”.

Why economists oppose the cut

In The Conversation’s pre-budget survey of 46 leading economists selected by the Economic Society of Australia, not one thought cutting the fuel excise a good idea. About a third rated it among the worst possible policies.

Their reasons are the uncertain economic benefit and inconsistency with important long-term policy goals to reduce dependence on oil-based imports, lower greenhouse gas emissions and cut government debt.

Frydenberg has promoted the cut as anti-inflationary, reducing consumer prices by 0.25 percentage points in the June quarter. But prices will simply rise by the same amount in the December quarter.

Global fuel prices may fall long before the end of six months. Last week benchmark oil prices fell 13% on news the US will release more from its strategic reserves as well as a truce in the long-running civil war in Yemen.

If oil prices drop the government will be adding billions of dollars to the deficit for no real economic gain. It could even be adding to underlying inflationary pressures by increasing household spending, pushing the Reserve Bank to increase interest rates sooner or by more.

Furthermore, while the fuel excise cut is legislated to be in place just six months, history shows governments find it hard to reverse cuts once implemented. In 2001, for example, the government of John Howard was panicked by poor opinion polls to suspend indexation of the petrol excise when prices reached $1 a litre. Indexation was not restored for 14 years, at a cost of more than $40 billion in forgone tax revenue.

Well distributed?

Economists prefer targeted measures, and the problem with cutting the fuel excise is that lot of the benefit will go to sustaining the driving habits of wealthier households.

On average those in the most affluent 40% of households drive about 50% more kilometres than those in the poorest 40%.

Read more: 5 maps that show why free public transport benefits the affluent most

Wealthier households are more likely to have second or third cars, and to have larger cars – such as SUVs – that use more petrol. They also have the money for leisure pursuits such as weekend getaways.

A better approach would be target help to businesses that must buy fuel and to those on low incomes, such as through a cash bonus, leaving it to them to decide if they want to spend on petrol or other things.

This would also help those without a car, those who do not drive much and those with electric vehicles, who all face cost pressures as petrol prices feed into prices at the supermarket.

John Hawkins is a former Treasury officer.

Yogi Vidyattama does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.