The Last Will And Testament is a work of weight and scope, and a rejoinder for anyone who feared that Opeth’s prog-rock expansionism had spoiled their appetite for heavyweight metal.

The Swedish prog-metal institution’s 14 studio album finds frontman/guitarist Mikael Åkerfeldt in storytelling mode, constructing audacious and at times monstrously heavy arrangements in service to this dark narrative.

This is Åkerfeldt as Ibsen, or perhaps as screenwriter/producer Jesse Armstrong, with a story that mines similar themes to Armstrong’s smash-hit HBO series Succession. Like Succession, The Last Will And Testament is the story of a malevolent patriarch and his legacy, albeit Åkerfeldt sets his tale in the 1920s.

The story and music work hand in glove. The album opens to the percussive echo of footsteps, shoe leather on stone, a Martin Mendez staccato bassline and a electric guitar melody that sounds like a plot device.

It’s like a thread that Åkerfeldt is willing us to pull on, just to see what happens next, and what happens is a lot of music, and revelations that unspool with each passing track. The brutal architecture of metal guitar is scaffolded by the swirl of Joakim Svalberg’s keys, Svalberg deploying Rhodes Piano, Moog and Mellotron to widen Opeth’s sound.

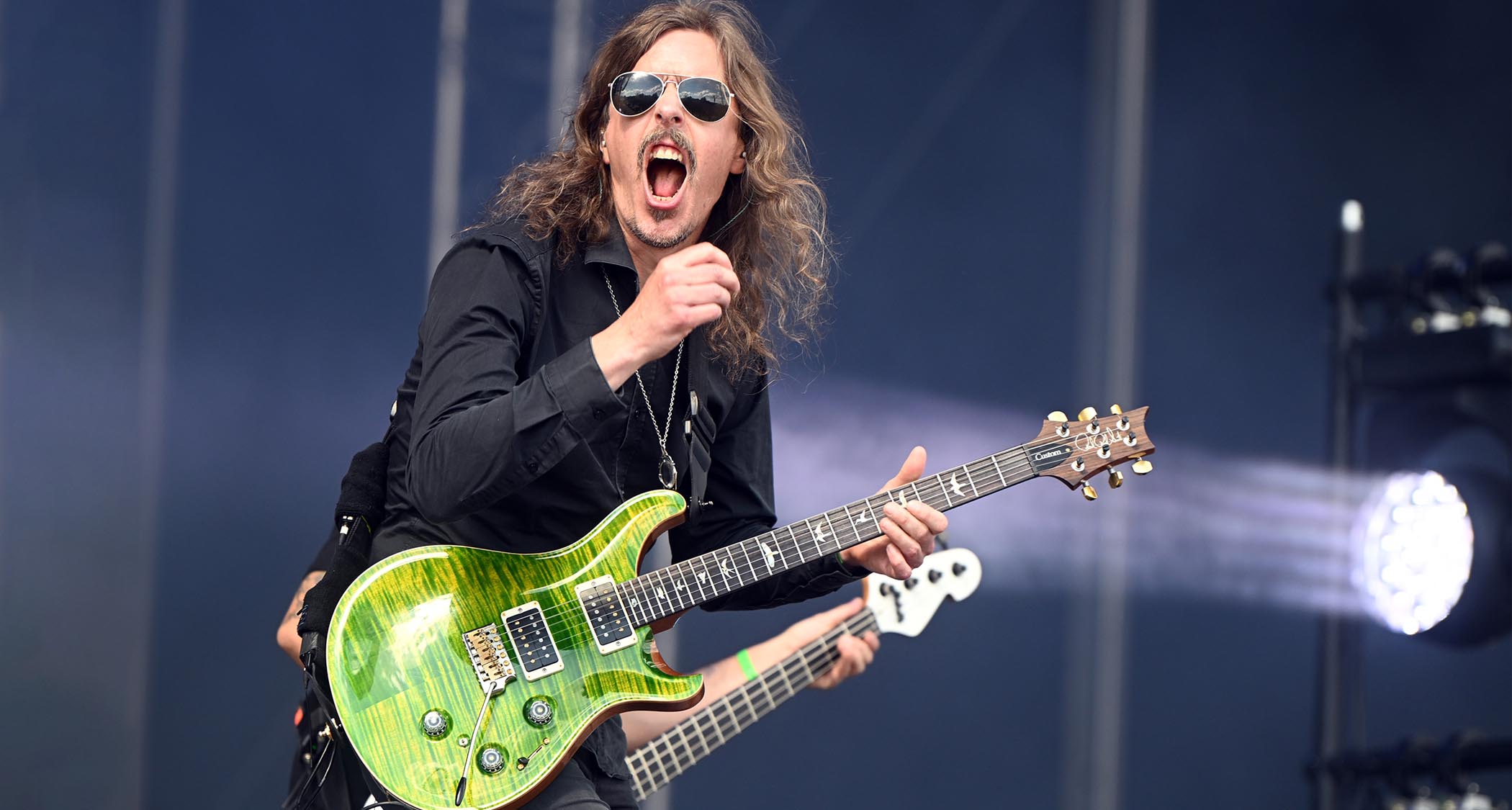

Death metal abuts rhythmically complex prog rock, with a lot of counting, feel changes, and occasions for lead guitarist Fredrik Åkesson to show us why Åkerfeldt considers him “the greatest guitar player in the world”. There is the much-celebrated return of Åkerfeldt’s peerless death metal vocal delivery.

There are Middle Eastern melodies (Ritchie Blackmore, reveal thyself!). There is a David Gilmour-esque solo. There are hand-claps keeping time. There are guest appearances from Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson, who offers spoken word and plays flute on a couple of tracks, and Europe’s Joey Tempesta, who sings backing vocals on one song.

Joining Opeth from Paradise Lost, Waltteri Väyrynen makes his debut on drums – “Incredible, insane,” is how Åkerfeldt describes his performance.

There is a lot of crazy shit going on, and an abundance of evidence to suggest that Opeth’s appetite for prog-rock and its freewheeling dynamics is what enables this to sound so heavy. At this stage in his career Åkerfeldt has become institutionalised by Opeth’s aesthetic ambition. Call it expansive – it sounds expensive – but to Åkerfeldt this is quote/unquote normal music.

I love to push vocals. I figure out in the middle in the middle of writing, like, ‘F**k, this is a bit out of my range!’ But I love to hear that type of suffering... I love to hear that struggle

“I know it’s probably a lot to take in for people, especially this record,” he says. “But I think over all the records we’ve done, there’s a lot of things going on. But to me that’s become normalised. I love that you said it sounds expensive. That’s a term we, or I, use a lot. ‘Something sounds expensive. There’s a lot of ingredients…’ When we were talking about effects, like reverb and echoes, we would often say this sounds like an expensive reverb [Laughs].”

Åkerfeldt even considered presenting The Last Will And Testament as one long piece but decided to split it up, numbering the tracks, and noting them with “§”, the section sign.

He was talked out of this typographically obtuse nomenclature – because, after all, who among us knows what the “§” is let alone where it is on a QWERTY keyboard? And so the songs would read, “Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2…” But there was a mixup. Åkerfeldt’s original preference, the “§”, remained. It all worked out in the end.

Whether Åkerfeldt has the spare vocal capacity to replicate this live remains to be seen. Even on record, it was a heavy lift. “I love to push vocals,” he says. “I figure out in the middle in the middle of writing, like, ‘Fuck, this is a bit out of my range!’ But I love to hear that type of suffering in not just my voice but in all vocalists – that it’s a bit out of their range. I love to hear that struggle. That sounds awesome to me.”

The sessions at Rockfield Studios, in Wales, pushed him to the limit. But this was what Åkerfeldt was going for. A more perfect version of the The Last Will And Testament exists on demo recordings, but when it was time to track for real, he wanted humanity, the sound of a performance being captured. The pursuit of perfection, he argues, is where modern metal bands are getting it wrong.

Even after listening to this album a whole bunch of times, I am not sure I feel prepared to talk about it – it might take a few years for it to really reveal itself in full.

“We can speak in a few years’ time as well!”

But where does it start? You’ve said you write by instinct?

“I trust my instincts. I don’t think too much. I guess I have some type of knowledge but it’s not from theory. It’s just from being a music fan, picking things up from lots of different genres

“There is some shit that I brought in from maybe a singer-songwriter record, or it could be a Paul Simon song – in fact, I did steal a thing from Paul Simon! And it could be a Dexter Gordon thing, and it could be a Morbid Angel thing, whatever. Not that I try to nick things necessarily but the sum of all these parts, it becomes normal to me.”

You absorb it. What you listen to very much becomes a part of your musical temperament. I wanted to ask about those musical epiphanies, and how you integrate them into Opeth.

“That’s how it’s always been for me. I was a young kid at some point, a long time ago [laughs], when when I was immediately affected by the sound of, for instance, Morbid Angel. And I was like, ‘How do they do that? What’s their sound?’ And after a while you feel like you write a riff and it’s like, ‘Oh fuck! It is kind of that Morbid Angel sound that I’ve been looking for.’”

“So my teachers, if you will, have not been generic music teachers; it has been bands and artists, and I am especially drawn to and gravitate towards the musicians that think a little bit outside of the box. I’m not really into generic – although, with that said, I do love generic music too, sometimes. But, generally, I gravitate towards musicians who are a bit odd.

“Like Trey Azagthoth, for instance. As far as I’m concerned, he is one of a kind. Nobody can write that music. If I was interviewing him, I would ask him the same thing: ‘How the fuck do you come up with these things? How is that in your kind of DNA, your blood, to write that? Like what did you listen to to to get to where you’re at?’ For me it is just a blend of so many different genres that our own genre is almost genre-less.”

Yes, absolutely. It is an Opeth record, and by that we know what sort of sensibility is at play. It is so incredibly dark – and it is heavy, and ornate and whatever – but it sounds so playful.

“It has to have fun. I’m never really bored when I write music. It is like playing with toys when you were a child, and that is a necessity for me. I need for it to be fun, otherwise it would kind of lose its purpose of being musician for me… my longing to experiment and develop those kinds of things, see what’s on the other side, discovery. That type of thing is important to me, to keep it interesting.

“Because if I look from the outside, I’m completely fucking boring! Which leads me to think about the thing that Charlie Watt said – that doesn’t have anything to do with this, and nothing to do with music but I just have to mention it because it’s the best saying ever – Charlie Watts from the Stones, he said, ‘I’m not bored. I just have an incredibly boring face.’ [Laughs]”

I am not sure you can make music when you are bored but there is definitely space for boredom. Moments of boredom lend themselves to contemplation, and then to the idea.

I can sit and look at at a tree. That’s my rest... I don’t have to do something all the time. But that helps me when I am doing something. Then, I’m kind of pumped up, I’m eager

“Now are you talking! I look at my children, our two daughters, the concept of boring is something they don’t even want to know about. They they can’t allow themselves to be bored, so they have to have a continuous stimulation from somewhere. And because I’m older, I can sit and look at at a tree. That’s my rest, so to speak.

“I don’t have to do something all the time. But that helps me when I am doing something. Then, I’m kind of pumped up, I’m eager. So in between being creative, I’m a slob basically.

“I almost forgot the interview today because I was playing videogames! [Laughs] Just being a child, just being a fucking idiot. I can sit and do nothing. That’s my point. I need that in my life, and I think that’s also necessity for me to be able to be creative once I decide to try and be creative.”

There’s an outro solo in Paragraph Six that is quite David Gilmour, sitting on top of a steel-string acoustic guitar.

“That was my solo actually. I am not a great guitar player. My strengths as a musician are those kinds of slow things, because I am a Peter Green fan and I like those guitar players, like Jerry Donahue [Fairport Convention].”

What did you use?

“Uh, good question. I think that was one of the few solos that I did back home, and it is actually done by a virtual amp. I think it was a Bluesbreaker, and a Telecaster.”

I am not a great guitar player. My strengths as a musician are those kinds of slow things, because I am a Peter Green fan and I like those guitar players, like Jerry Donahue

“Yeah, it’s the Universal Audio thing that comes with my Pro Tools setup. I have a subscription with Universal Audio, so I have – I don’t know how many amps and fucking preamps, and EQs, all these kinds of things!

“Normally, I am a defender of ‘real’. We rerecord everything from demo stages. But this one, I was listening to it in the studio, looking at the boys – and especially Fredrik, who is a gear freak – and I was like, ‘I think this sounds great. There’s no need to redo. To redo it might risk it getting worse or whatever. Keep it – even if it’s a virtual amplifier.’

“But thats the only exception on this record – it’s funny you would bring that solo up. That’s the only one I didn’t redo, or that we didn’t redo, so it’s something that stuck from the demo.”

So you rerecorded everything else from the demos at Rockfield?

“Yeah, pretty much everything from the virtual instruments. I do all the demos, and if you heard the demo, you would be like, ‘This is a fucking good sounding demo.’ Like, everything sounds good.

I love guitar heroes myself, but I am also the songwriter and I am very specific when I feel it is time for shredding and when it is time for soulful, long notes

“I programmed the drums, almost exactly how it’s gonna be on the records. Same with keyboards. And I can’t play drums or keyboards but I can fake it on a demo. We used those demos as templates and gradually replaced everything.”

That’s when the real work begins.

“We started with muting the demo drums, and Walt played along to the demo. I played a little bit of virtual Mellotron actually because the response from a real Mellotron is too slow for some of the faster parts of the album. It is almost impossible to play. We did all the Mellotron strings on a real mellotron here, and then Joachim did the Hammond organ, the Moogs, the Fender Rhodes at his studio, so they are all real.

“That’s always what we are aiming for, to replace [the virtual] with a real instrument. What we are after is not perfection. When you’re replacing a virtual instrument with a real instrument, you’re looking for the flaws. You’re looking for the noise. You’re looking for the earth hum. You’re looking for the arm-tight playing, so to speak. You are looking for the human aspect.”

There is a humanity in imperfection.

“Yeah, and that is something you don’t get in the demo. If you listen to my demo, it’s fucking perfect, and I am – again – a defender of the human sound, which is why I am not necessarily crazy about modern metal records, where everything is quantised down to a tee, and it’s perfect, it’s computerised. It just doesn’t sound right to me.

“The demos I do are like that. It’s good to have a perfect template and then you kind of fuck it up a little bit when you record it, and it becomes a human-sounding record in the end.”

What was used on A Story Never Told? That clean is so pleasing to the ear. Do you remember what guitar amp you used for that tone?

“That was Fredrik’s solo and he did all his solos back home in his studio. But he wouldn’t be able to live with himself if it wasn’t a real amplifier. Fredrik knows his shit. We had a hand-wired Friedman, one of the early Friedmans that was soldered by [Dave] Friedman himself. I can’t remember what it is called that but that is the one that we used for the bulk of the record.

“[Fredrik] has this 1970s Strat in which I think he has changed the pickups in it, with slightly more gain. What’s it called, FS-H or something like that? I am not sure what they’re called. But it was an old Stratocaster [most likely this was Åkesson’s 1970 Strat once owned by John Norum, which like all Norum’s Strats would have DiMarzio FS-1 single-coils].

“I had requested a Gilmore-esque, Blackmore-esque solo for this song, because with the song coming in at the very end, and because the record is so dynamic and so crazy, and so in your face and so dense, I wanted the last song to be like a breather.”

Sure, it is is the epilogue of the story

“Yeah, it is. I wanted people to just think, ‘What the fuck has just hit me!?’ And then calm down with this song, after these pretty intense seven songs. And the same goes with that solo.

“Frederik comes from a metal, shredder background, so in the beginning, when he joined the band, I had to kind of put a leash on him a little bit because he wanted to show [us] the new licks and he wanted to kind of establish himself.

“I mean, he was established in Sweden as a one of the top guitar players, but he had this kind of arena where he wanted to establish himself as a musician, so I think he was he was thinking in terms of skills. I love his guitar. I think he’s the fucking best guitar player in the world, but I had to pull him back a little bit in the early days.”

Well Fredrick was coming out of that Arch Enemy milieu, speed and technicality.

“Yeah, that’s a very good point. He was in Arch Enemy before he joined us, for a brief moment there. And he was in a Swedish band called Talisman, which had two ex-Yngwie Malmsteen guys in the band, Marcel [Jacob] and Jeff Scott [Soto], so he comes from that background of guitar heroes. I love guitar heroes myself, but I am also the songwriter and I am very specific when I feel it is time for shredding and when it is time for soulful, long notes.”

Did you have to give him any direction?

“I didn’t really have to say anything to Fredrik. He knows when to hit the brakes, and he knows when to put it in the top gear, and for A Story Never Told I didn’t have to say anything to him. He just did that amazing solo and that was it. I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s awesome.’”

And Ritchie Blackmore was the influence?

“He’s like, ‘Yeah, I put together this solo. I was listening to Bent Out Of Shape, by Rainbow, and there’s a song on there called Snowman, really slow...’ That’s why I love Blackmore so much because he has all these tricks, and he was a great player, but he was so musical in his playing.”

I admire musicians who say that, ‘I was inspired by Chinese music from the 1350s, like with the dynasty of whatever,’ and they put together something that sounds a bit Chinese or whatever. But I don’t have those answers

Obviously, this is a concept record, with a story to tell. But do you look at songwriting as a form of storytelling?

“With this album, yeah, I guess. To a certain extent. But that is not my forte. Most of our records, most of our songs, famous albums, I don’t know what the fuck the lyrics are about. Like, I forget what they are about – and I have to make something up [Laughs].”

That doesn’t matter though, does it, because that’s the audience’s job, too. They are the second author of the work.

“Right! They filter the music through themselves and they find their own kind of meaning to it. Of course I have written some lyrics that mean something to me personally, and with this new album, there’s a concept, there’s a story. But I don’t really consider myself a storyteller unless I have a story, and this time I happen to have one.”

What’s the biggest thing you’ve learned about yourself from making a record like this?

It sounds a bit pretentious but when I’m writing it’s almost like part of my consciousness is not even present

“I act so much and write so much upon instinct, and I work fast too, I don’t remember. I experiment so much and I don’t really take notes. A lot of things that I end up liking are the product of a mistake. You do it completely the wrong way and then all of a sudden you have something, a sound or a whatever that you think, ‘Huh? That’s cool. I’m gonna keep that.’ But I don’t know how I came up with it, and so I don’t really know what I learned. I don't break everything down the end.”

Maybe it is best not to. There is something to this idea of working fast because it can be hard to get your consciousness up and running so when it is firing don’t interrupt it.

“It sounds a bit pretentious but when I’m writing it’s almost like part of my consciousness is not even present, like a different part of my brain takes over and this other one is switched off, so it feels like almost like I’m not even there.

“I don’t really have memories about doing things or how I did things. All of a sudden, I know that I’ve been working and I’ve been down in the studio working, and in the end there’s a record, but how it came, the technical aspect, or why I wrote this?’ I have no fucking clue.”

That’s one of the great pleasures of creating, being able to step away from being self-aware for five minutes.

“Yeah, but also, I admire musicians who have an answer to questions like that, who say that, ‘I was inspired by Chinese music from the 1350s, like with the dynasty of whatever,’ and they put together something that, yeah, maybe it sounds a bit Chinese, whatever. But I don’t have those answers.

“I like to think of myself as a musician. I’m a product of the music I consume. Over the years, and I’m 50 years old now, so there has been a lot of music that I have been listening to over the years, and of course lot of that would rub off on my own writing. But ultimately I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing!”

- The Last Will And Testament is out 22 November via Reigning Phoenix.