Some national borders are determined by natural phenomena like seas, mountains and rivers. Most, however, are created by people.

This means the creation of borders is often a political exercise – usually informed by the interests of those who create them, not the local populations to whom they apply.

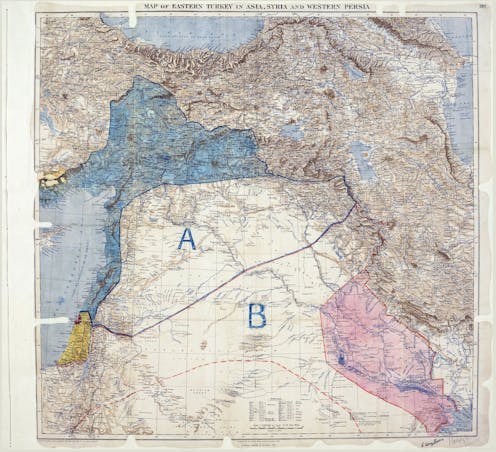

The Sykes-Picot agreement, known officially as the Asia Minor Agreement of 1916, was arguably the first in a series of attempts by colonial powers to mould the borders of the Middle East.

Signed in secret at the height of the first world war, Sykes-Picot was an agreement between France and Great Britain, approved by Russia. It would have lasting consequences for the region.

It is frequently cited as the epitome of European colonial betrayal, and the genesis of most conflict in the Middle East.

But while Sykes-Picot did significantly affect regional politics, the history is more complicated than popular narratives suggest.

‘The Eastern question’

The agreement was seen by the signatories as a potential answer to what was then known by European powers as “the Eastern question”: what would happen when the Ottoman Empire inevitably collapsed?

The Ottoman state in the early 20th century was vast compared to its European peers, encompassing Anatolia (the Asian part of modern-day Turkey) and parts of the Arabian Peninsula.

But it was weak, and had been on a steady decline since the 18th century due to multiple military defeats, revolts and rampant corruption. By the beginning of the first world war, the Triple Entente (France, Britain and Russia) believed the Ottoman state would not survive long.

The Entente aimed to create new “zones of influence” in the Middle East, dividing Ottoman territory into colonial partitions.

Secret negotiations

Between late 1915 and early 1916, Britain and France sent their respective envoys to negotiate the potential terms of this outcome in secret.

Mark Sykes, a political adviser and military veteran, represented the British. François Georges-Picot, a career diplomat, represented the French.

Italy and Russia also had delegations in attendance, though the discussions were dominated by Britain and France as the most powerful nations. The Ottomans were oblivious to these negotiations.

Under the agreement:

- France was allocated what is now Syria, Lebanon and southern Turkey

- Britain claimed most of modern-day Iraq, southern Palestine and Kuwait

- Russia took control of Armenia.

An area known as the Jerusalem Sanjak (an administrative division created by the Ottomon Empire) in Palestine was to come under an international protectorate, though it was not settled in the agreement as to how this protectorate would operate.

Sykes-Picot was kept secret, mostly because Britain had made contradictory commitments to other parties. It had promised (through a series of letters known as the McMahon-Hussein correspondence) to give independence to the Arabs who had helped the British fight the Ottomans in the first world war.

Later, in early November 1917, it also made a promise to Zionist Jews migrating to Palestine in the Balfour Declaration. In this public declaration, Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur Balfour effectively expressed Britain’s support for the Zionist project to create a Jewish state in Ottoman Palestine. Then-Prime Minister David Lloyd George also publicly supported both Zionism and Balfour’s statement.

The Sykes-Picot agreement did not stay secret for long.

In November 1917, the Bolsheviks, who were now in power in Russia following the fall of the Russian monarchy, published Sykes-Picot to the world.

Arab nationalists were enraged. So, too, were Zionists who had witnessed the Balfour Declaration just weeks prior. The Anglo-French declaration of November 1918 attempted to allay the fears of the Arabs by pledging to “assist in the establishment of national governments and administrations.” However, Arab distrust of the European powers only grew.

Borders moulded by colonial powers

In the years following, European powers started to reevaluate their position on Ottoman territory.

The French, who still wished to take control of Syria, had argued the newly formed League of Nations (a predecessor of the United Nations) could give France the territory under a mandate. A mandate is a formal authorisation to govern by the League of Nations.

The British said this would violate their earlier promises to the Arabs. Britain reiterated that the Anglo-French declaration of 1918 superseded Sykes-Picot.

Then came the San Remo Conference in 1920, an international meeting in Italy. This is where some of the popular readings into Sykes-Picot get muddled, as several aspects of the agreement were discarded. What remained the same was the French and British desire to add Ottoman territory to their dominions.

Here, the European victors of the first world war sought to finalise the division of Ottoman territories by slicing them into League of Nations mandates.

This included the French mandates of Syria and Lebanon, as well as the British mandates of Palestine and Mesopotamia. Britain also confirmed at the time its support for a Jewish national homeland, while protecting the local Palestinian population.

This is where we start to see borders of the modern Middle East form. The boundaries themselves differed from Sykes-Picot. But Britain and France, however, were still able to expand their colonial dominion in the region.

In 1921, a group of British representatives met in Cairo to finalise the borders of their mandates. This led to the creation of two states: Iraq under King Faisal and Transjordan (now Jordan) under King Abdullah – both of whom were members of the Arab Heshemite dynasty. Palestine was to remain under British mandatory control.

While these states had independence on paper, then-Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill believed that Transjordan would ultimately be controlled by the British Empire, giving the Heshemites only nominal independence.

Little consideration was given to the ethnic and religious diversity of these territories. Some argue this helped lead to modern-day sectarian conflict in Iraq.

Ripples that continue today

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire was always going to cause regional upheaval, but the colonial jockeying for territory clearly had lasting consequences.

Several regional conflicts were exacerbated during this period, but it would also directly lead to the creation of the state of Israel and the Arab-Israeli conflict.

This leads to the displacement of Palestinians and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict that still rages today.

Zionists and Arab nationalists viewed Palestine to have been originally promised to them by the British through the Balfour Declaration and McMahon-Hussein correspondence, respectfully.

But in Sykes-Picot, the British had no intention of promising Palestine to anyone but themselves.

As a result, the British mandate was characterised by anti-colonial violence from both Jews and Arabs.

When the British eventually abandoned control of Palestine in 1947, the UN partition plan for two states (one Jewish, one Arab) was supposed to take over. Instead, Arab-Israeli conflict began within hours of the partition taking effect.

So a lot happened after Sykes-Picot, with the map proposed in 1916 looking very different to what actually eventuated.

Many scholars argue it was the agreements that followed Sykes-Picot that were more consequential, and Sykes-Picot holds only “minor importance” by comparison.

While this may be true, Sykes-Picot is still emblematic of how consequential European colonial ambition was in the Middle East.

And while the borders outlined in the agreement did not eventuate, Britain and France still managed to get most of the territory they wanted, with little consideration of local populations.

The Sykes-Picot agreement is therefore one of many colonial projects that we are still feeling the ripples of today.

Andrew Thomas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.