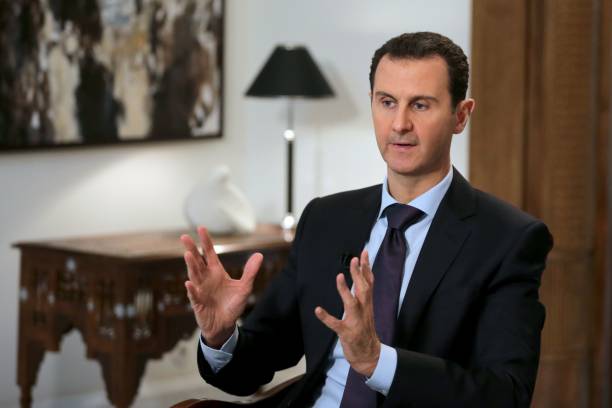

The Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad has fallen, bringing a shocking end to his family’s 50-year reign following a lightning offensive by Islamist rebels.

The president’s whereabouts remain unknown after reports he left Damascus early on Sunday as opposition fighters entered Damascus.

It was the first time opposition forces had reached the capital since 2018 when Syrian troops recaptured areas on the outskirts of the capital following a years-long siege.

A video shared on Syrian opposition media showed a group of armed men escorting Syrian prime minister Mohammed Ghazi Jalali out of his office and to the Four Seasons hotel on Sunday.

Interventions by Russia, Iran, Hezbollah and others have allowed him to remain in power within the parts of Syria under his control. But no international help for the deposed leader appears forthcoming.

Incoming US president Donald Trump wrote on his social media platform Truth Social: “Assad is gone. He has fled his country. His protector, Russia, Russia, Russia, led by (President) Vladimir Putin, was not interested in protecting him any longer,”

Here is a look at some of the key aspects of the new developments:

What’s the latest?

The military command of the Syrian opposition says its fighters have entered the capital Damascus claiming that it is “free” of President Bashar Assad’s rule.

The so-called Military Command Administration said Assad had fled without giving further details.

His departure marks the end of the 54-year Assad family rule of Syria with an iron fist. His father Hafez Assad came to power in a bloodless coup in 1970 and ruled until his death in 2000. Bashar Assad was elected weeks after his father’s death and ruled Syria until he was overthrown on Sunday.

The command declared the end of “the dark period and the beginning of a new era in Syria”.

State television in Iran - Assad’s main backer in the years of war in Syria - reported “terrorists” had entered Damascus and that Assad had left the capital.

An Associated Press journalist in Damascus reported seeing groups of armed residents along the road on the outskirts of the capital and hearing gunshots. The city’s main police headquarters appeared to be abandoned, its door left ajar with no officers outside.

Another shot footage of an abandoned army checkpoint, uniforms discarded on the ground under a poster of Assad’s face.

In the early hours of Sunday, Syrian rebel commander Hassan Abdul Ghany said that insurgent forces “fully liberated” Syria’s central city of Homs.

A rebel commander said they had also taken control of an army camp and villages outside the city.

The Syrian military, which has been reinforcing Homs and hammering the rebels with intense airstrikes, did not immediately comment on the reports.

Homs, parts of which were controlled by insurgents until 2014, is a major intersection point between Damascus and Syria’s coastal provinces of Latakia and Tartus, where President Assad enjoyed wide support and where his Russian allies have a naval base and airbase. Homs province is Syria’s largest and borders Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan.

Earlier the rebels said they seized control of the southern city of Daraa – the birthplace of the 2011 uprising against Assad – as they pressed on with their lightning advance.

The Syrian army withdrew from much of southern Syria on Saturday, leaving more areas of the country, including two provincial capitals, under the control of opposition fighters.

“This change presents an opportunity to build a new Syria based on democracy and justice that secures the rights of all Syrians,” the leader of the Syrian Democratic Forces Mazloum Abdi said in a written statement, praising the fall of the “authoritarian regime in Damascus”.

The Kurdish-led group has a significant presence in northeastern Syria, where they have clashed with the extremist Islamic State group and Turkish-backed militias over the years.

Rebel commander Colonel Hassan Abdulghani said the insurgents advanced in the countryside around Idlib, putting all of the province of the same name under their control. This could not be independently confirmed.

Military vehicles abandoned by Syrian troops dotted the roads in Khan Sheikhoun in Idlib province as people posed and took pictures atop an abandoned tank on a highway.

What implications could the insurgency have?

The Islamist rebels dealt a major blow to the influence of Russia and Iran in the heart of the region, key allies who propped up Assad during critical periods in the conflict.

The collapse followed a shift in the balance of power in the Middle East after many leaders of Lebanon’s Iranian-backed Hezbollah group, a lynchpin of Assad’s battlefield force, were killed by Israel over the past two months. Russia, Assad’s other key ally, has been focused on the war in Ukraine.

Turkey-backed Syrian forces have taken control of some 80 per cent of northern Syria’s Manbij area and are close to victory against Kurdish forces there, a Turkish security source said. Stabilising western areas of Syria captured in the rebels’ advance will be key. Western governments, which have shunned the Assad-led state for years, must decide how to deal with a new administration in which a globally designated terrorist group - Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) - looks set to have influence.

The US will continue to maintain its presence in eastern Syria and will take measures necessary to prevent a resurgence of the Islamic State, deputy assistant secretary of defence for the Middle East Daniel Shapiro told the Manama Dialogue security conference in Bahrain’s capital on Sunday.

Before its defeat, Islamic State imposed a reign of terror in large swathes of Syria and Iraq.

At a conference in Doha, Turkish foreign minister Hakan Fidan said “terrorist organisations” must not be allowed to take advantage of the situation in Syria, and called on everyone to act with caution.

HTS, which spearheaded the rebel advances across western Syria, was formerly an al Qaeda affiliate known as the Nusra Front until its leader, Abu Mohammed al-Golani, severed ties with the global jihadist movement in 2016.

“The real question is how orderly will this transition be, and it seems quite clear that Golani is very eager for it to be an orderly one,” said Joshua Landis, a Syria expert and director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma.

Golani will not want a repeat of the chaos that swept Iraq after US-led forces toppled Saddam Hussein in 2003, he said, adding: “They are going to have to rebuild ... they will need Europe and the US to lift sanctions.”

HTS is Syria’s strongest rebel group and some residents remain fearful it will impose draconian Islamist rule or instigate reprisals.

Assad has been at war with opposition forces seeking his overthrow for 13 years, in a conflict which has claimed an estimated 500,000 lives. Some 6.8 million Syrians have fled the country over the course of the war, mostly resettling in Turkey. Nearly 1.3 million people have been granted protection in EU countries, as of last year.

The US has around 900 troops in northeast Syria, far from Aleppo, to guard against a resurgence by the Islamist terror group Isis.

Both the US and Israel conduct occasional strikes in Syria against government forces and Iran-allied militias. Turkey also has forces in Syria and has influence with the broad alliance of opposition forces storming Aleppo.

What do we know about the group leading the insurgency?

The US and UN have long designated HTS as a terrorist organisation.

Its leader, Abu Mohammed al-Golani, emerged as the leader of al-Qaida’s Syria branch in 2011, in the first months of Syria’s war. His fight was an unwelcome intervention to many in Syria’s opposition, who hoped to keep the fight against Assad’s brutal rule untainted by violent extremism.

Golani early on claimed responsibility for deadly bombings, pledged to attack Western forces and sent religious police to enforce modest dress by women.

He has sought to refashion himself in recent years, renouncing his al-Qaida ties in 2016, disbanding his religious police force, cracking down on extremist groups in his territory, and portraying himself as a protector of other religions, including by allowing the city of Idlib’s first Christian mass in years.

What is the history of Aleppo in the war?

At the crossroads of trade routes and empires for thousands of years, Aleppo is one of the centres of commerce and culture in the Middle East.

Aleppo was home to 2.3 million people prior to the war breaking out in 2011. Rebels seized the east side of the city in 2012, and it became the proudest symbol of the advance of armed opposition factions.

In 2016, government forces backed by Russian airstrikes laid siege to the city. Russian shells, missiles and crude barrel bombs – fuel canisters or other containers loaded with explosives and metal – methodically levelled neighbourhoods. Starving and under siege, rebels surrendered Aleppo that year.

The Russian military's entry was the turning point in the war, allowing Assad to stay on in the territory he held.

This year, Israeli airstrikes in Aleppo have hit Hezbollah weapons depots and Syrian forces, among other targets, according to an independent monitoring group. Israel rarely acknowledges strikes at Aleppo and other government-held areas of Syria.