On March 26, 2024, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) began hearing arguments in a case that could have potentially limited access to abortion pills throughout the country. On June 13, the court unanimously ruled that the plaintiffs did not have legal standing, and so the trial concluded and no added restrictions were placed on the pill.

The pill discussed in the case, called mifepristone, is one drug in a two-pill regimen commonly prescribed for medication abortions. The Supreme Court did not agree to discuss the drug's approval that has stood for more than 20 years. Rather, the court could have rolled back regulatory changes made by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to make it easier to access mifepristone. These changes include the ability to get the pill by mail without an in-person doctor's visit, for example.

Here's what you need to know about mifepristone and the now-concluded Supreme Court case.

What is mifepristone?

Mifepristone is one pill in a two-pill regimen approved to induce a medication abortion, which uses drugs, rather than a medical procedure, to end a pregnancy. Medication abortions can take place in a clinic under a doctor's supervision, but they're also a safe and rigorously tested method for self-managed abortion outside a medical setting, Dr. Melissa Simon, a professor and obstetrician-gynecologist at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, previously told Live Science.

Related: State abortion bans may limit access to drug used to treat lupus and cancer

The two-pill regimen involves taking mifepristone by mouth, waiting 24 to 48 hours, and then taking the second pill — misoprostol — by placing it in the vagina, under the tongue or in the cheek. Mifepristone blocks the hormone progesterone, which the body needs to maintain a pregnancy, and misoprostol induces contractions that empty the uterus.

(Misoprostol, which is also used to treat other, non-pregnancy-related conditions, is not as tightly regulated as mifepristone, and its regulation has not been challenged in court.)

In the U.S., two-pill medication abortions can be used to end a pregnancy through 10 weeks gestation, or up to 70 days from the first day of a person's last menstrual period. Mifepristone should not be used in cases of ectopic pregnancy, in which a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, and people with intrauterine devices (IUDs) should have these devices removed before taking the pills, the FDA cautions. The pills can also be used in the treatment of pregnancy loss.

Misoprostol can be used without mifepristone to safely induce abortion. However, the two-pill regimen is preferred because people tend to experience milder side effects when taking both, and studies suggest taking both pills is more effective. Taking misoprostol alone tends to result in more nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and a longer period of cramping and bleeding.

How safe and effective is mifepristone?

Studies show that the two-pill medication abortion regimen that includes mifepristone is very safe and effective.

According to the KFF, studies suggest medication abortion successfully terminates the pregnancy 99.6% of the time, with a 0.4% risk of major complications and an associated mortality rate of less than 0.001%.

—Abortion laws by state: https://reproductiverights.org/maps/abortion-laws-by-state/

—For questions about legal rights and self-managed abortion: www.reprolegalhelpline.org

—To find an abortion clinic in the U.S.: www.ineedanA.com

—Miscarriage & Abortion Hotline operated by doctors who can offer expert medical advice: Available online or at 833-246-2632

—To find practical support accessing abortion: www.apiarycollective.org

The FDA notes on the label for mifepristone that the regimen has a 97.4% success rate, based on U.S.-based clinical trials. (The exact numbers vary slightly between different studies and the groups of people included.)

A 2024 study also found that receiving mifepristone via telehealth is as safe and effective as having it prescribed in person. The study followed 6,000 people who had telehealth abortions, 97.7% of whom successfully terminated their pregnancies without additional treatment. About 0.25% experienced serious side effects, some of which required blood transfusions.

Related: 8 Supreme Court decisions that changed US families

When was mifepristone approved?

The FDA first approved Mifeprex, a brand-name version of mifepristone, for use in 2000. The pill was initially approved for use through seven weeks gestation, and then in 2016, the FDA extended its approval to 10 weeks.

The agency approved a generic version of Mifeprex in 2019. And as of 2021, the agency has allowed people to receive medication abortion pills by mail after a telemedicine appointment, rather than needing to get them in person from a certified health provider at a specialized clinic. The FDA also now allows certified pharmacies to dispense the pill to people with a prescription, following a regulatory change made in 2023.

How did mifepristone end up in the Supreme Court?

SCOTUS heard a case about mifepristone because the pill had been challenged in several lower courts.

The pill was first challenged in April 2023, when a federal district judge in Texas ruled that the FDA's approval of mifepristone in 2000 was unlawful and should be suspended. The judge's ruling would have taken effect across the entire country unless a higher court issued a stay, or an order to halt the legal proceeding.

On the same day as the Texas ruling, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an appeal and called for an immediate stay of the decision. Meanwhile, the FDA appealed the decision, and the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals then ruled that mifepristone's long-standing approval should be left alone.

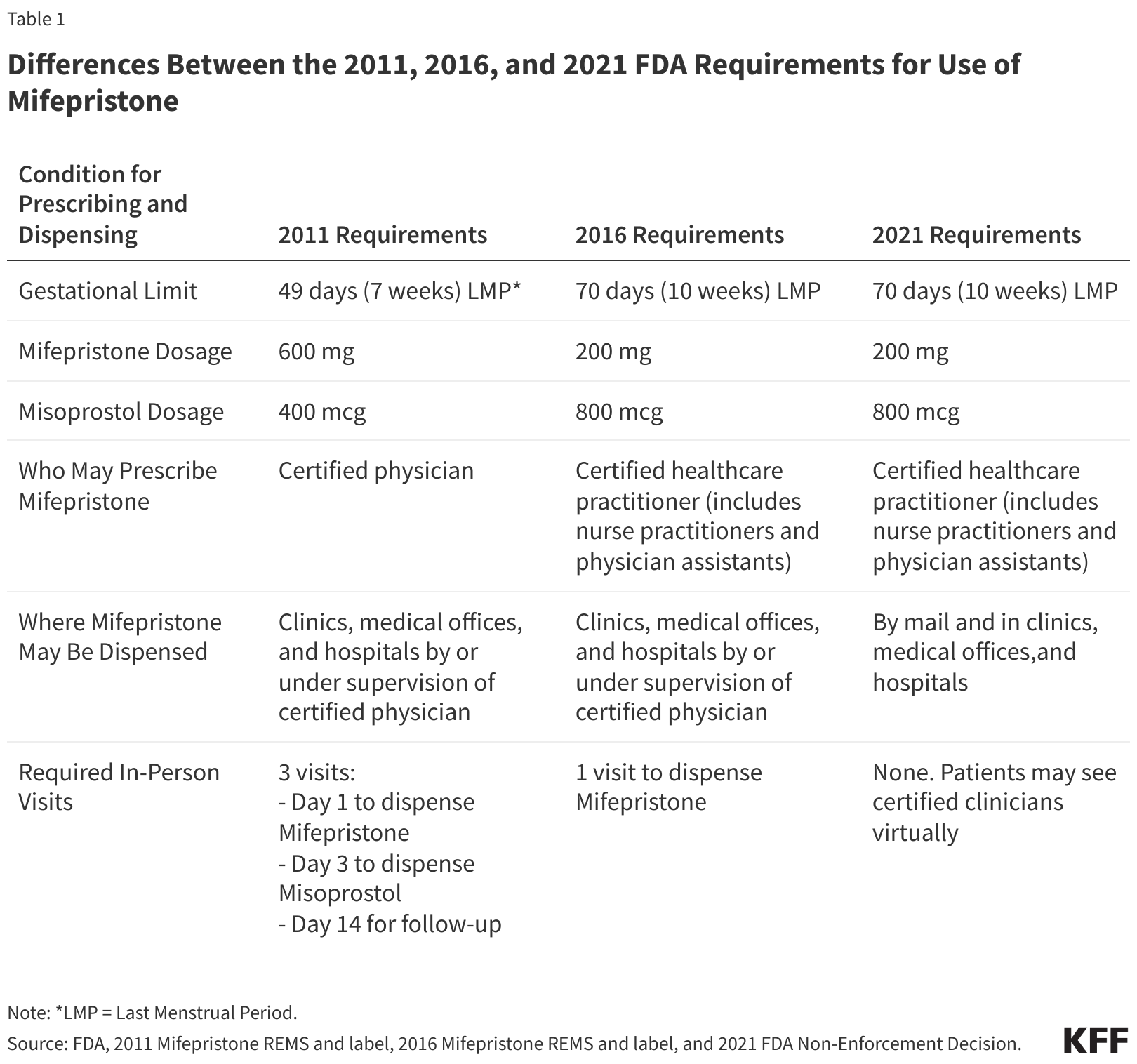

However, the appellate court argued that the FDA's regulatory changes in 2016 and 2021 should be rolled back. This change would have reinstated the requirement for patients to receive the pill in person from a certified doctor, thus stopping nurse practitioners, physician assistants and pharmacies from dispensing the drug in person or via mail.

Both the plaintiffs (anti-abortion groups) and the defendant (the FDA) appealed the court's rulings.

What happened in the Supreme Court's trial about mifepristone?

Starting on March 26, 2024, the Supreme Court began reviewing the appellate court's decision in a case called "FDA v. the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine" (AHM). AHM is a collective of anti-abortion groups that includes doctors.

SCOTUS said it would not review the FDA's original approval of mifepristone. Rather, it would first address the question of whether AHM had legal standing to sue the FDA over its regulation of the pill.

AHM argued it did because its members may end up treating patients experiencing side effects of the drug, which could divert resources from their other patients. In addition, treating the patients would violate the doctors' moral stances around abortion, the plaintiffs said.

On June 13, SCOTUS ruled that AHM did not have legal standing and thus ended the case.

Stakeholders in the pharmaceutical industry and medical ethics experts had worried that, if the court were to rule that AHM had standing, it could have opened the door for doctors to sue over any drug approval they disagree with, regardless of that drug's safety or effectiveness. Future challenges could be leveraged at the HIV-prevention drug PrEP or against medications used in gender-affirming care, for instance, according to KFF.

It could have also opened the door for drug companies to sue the FDA when the agency denies one of their products an approval, or for patients who experience side effects from a drug to sue in order to bar other patients from accessing the medicine, The Washington Post reported.

Had SCOTUS decided the plaintiffs had standing, the court would have also discussed whether the FDA's 2016 and 2021 regulatory changes around mifepristone were "arbitrary and capricious." In brief, AFM claimed that the FDA did not conduct adequate research to evaluate all of the possible effects that could come from expanding access to the pill in various ways, and the 5th Circuit Court agreed with that stance.

Had SCOTUS ruled similarly, the court's decision could have rolled back the rules around mifepristone to how they were back in 2011.

In addition, many argued that the move would have brought the FDA's authority to regulate drugs into question, with far-reaching implications beyond the realm of reproductive health.

Editor's note: This story was last updated on June 13, 2024, with information about how the case was resolved. The article was first published on April 10, 2023.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!